Jan 31, 2019

Shell pledges to 'do it all' as cash surge underpins returns

, Bloomberg News

Royal Dutch Shell Plc (RDSa.N) came through a quarter of volatile oil prices to beat earnings estimates, delivering a surge in cash flow the company said will underpin “world-class” returns to investors.

The better-than-expected performance should help to ease questions about whether Shell can simultaneously afford to reduce debt and complete its share-buyback program, while also paying one of the world’s largest cash dividends. Yet it also underlines some analysts’ concerns about the level of investment, as replacement of reserves fell well below average.

Shell urged investors to focus on returns as the company paid its entire dividend in cash, curbed debt and started the next tranche of its US$25 billion buyback program.

"We’re going to do it all, we need to do it all,” Chief Financial Officer Jessica Uhl said in a Bloomberg television interview. “It’s important for you to understand the nature of Shell, the nature of our cash flows, which aren’t necessarily dependent on excessive levels of capital investment.”

The Anglo-Dutch oil major earned US$5.69 billion in the fourth quarter of 2018, adjusted for one-time items. That’s up from US$4.3 billion a year earlier, beating the average estimate of US$5.39 billion.

Investors reacted positively to the results, with Shell’s B shares rising as much as 4.4 per cent, the biggest intraday gain in eight weeks. The stock traded up 3.8 percent at 2,372.5 pence as of 10:30 a.m. in London.

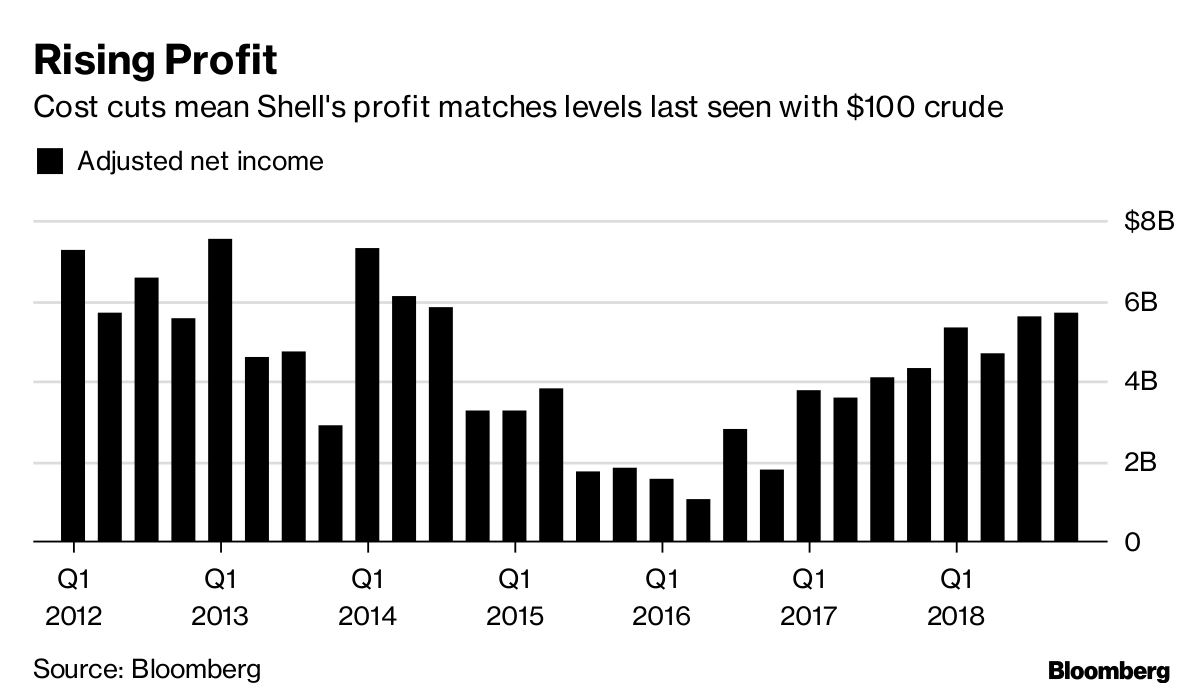

Profit was the highest for the period in at least six years, matching an era when oil was closer to US$100 a barrel. Chief Executive Officer Ben Van Beurden has made lowering costs a priority, first to survive crude’s collapse from 2014 to 2017, and then to keep the company competitive in case prices stay lower.

Reserves Replacement

While that’s helped boost profitability, some analysts have debated whether Shell is at risk of under-investing. Martijn Rats of Morgan Stanley said $65 oil, above today’s price, may be too low for the company to continue its breakneck pace of shareholder distributions while maintaining sufficient spending to boost reserves.

Shell said it didn’t discover enough new oil and gas reserves to cover what it pumped last year. It added 700 million barrels in new reserves, and produced about 1.4 billion barrels. As a result, its reserve-replacement ratio was 53 percent, well below the three-year average of 96 per cent. The number was affected by the de-booking of a giant Dutch gas field, ordered to close after causing earthquakes.

Uhl insisted that Shell can achieve growth, complete its buyback program and distribute dividends at US$60 oil, while Van Beurden said new projects will deliver 150,000 barrels a day this year, “more than enough” to offset declines.

Cash Engine

Uhl argued against being fixated on reserves since Shell’s exploration and production unit generates less than half of its cash flow. The refining and marketing, and integrated gas businesses both did better than analysts expected, buoyed by trading and the startup of a U.S. chemicals plant.

Cash flow from operations, a crucial measure of the sustainability of spending on new projects and payouts to investors, was US$22 billion, three times the level a year earlier. That figure benefited from a US$9.1 billion positive move in working capital in the fourth quarter, mainly due to the decline in crude prices and lower inventory levels.

The headline cash-flow number was strong but the underlying figure remained volatile and was slightly weaker than expected, Biraj Borkhataria, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, said in a note.

Despite several quarters of strong profits and cash generation, Shell’s dividend yield suggests it hasn’t fully convinced investors with its “do it all” message. Its shares are trading at a level that implies a dividend yield of about 6 percent, well above its peers Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp., but on a par with Total SA and BP Plc.

Fourth-quarter oil and gas output was 3.79 million barrels of oil equivalent a day, compared with 3.76 million a year earlier. Gearing -- the ratio of net debt to total capital -- was 20.3 per cent at the end of 2018, down from 25 per cent a year earlier.