Sep 14, 2021

‘Showing Its Teeth’: EU’s Path to a Showdown Over LGBTQ Rights

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The European Union has a dismal track record when it comes to disciplining countries within its ranks. But this month it opened several new fronts in its increasingly contentious battle with its own member countries over the bloc’s core values.

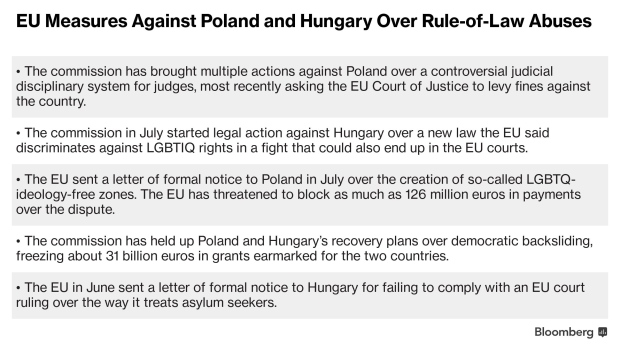

The EU this month threatened Poland with daily fines and frozen payouts in disputes over LGBTQ discrimination and judicial independence. Driven by several prime ministers, the bloc is harnessing powerful new budgetary tools in an unprecedented push to compel Poland and Hungary to reverse moves that undercut the rule of law or lose access to billions of euros.

This account of how the EU finally decided to take on Hungary and Poland is based on interviews with diplomats and officials briefed on conversations among leaders and the debate within the bloc’s executive. The push crystallized at an emotional EU summit in June, when Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban was taken aback by the fervency and unity of other leaders on the LGBTQ issue, and Sweden’s Stefan Lofven pointed colleagues toward how the EU could leverage its budget to bring the rogue nations to heel.

“The European Commission is finally showing its teeth,” Nathalie Tocci, visiting professor at the Harvard Kennedy School and director of the Institute of International Affairs in Rome, said in an interview. “In Europe, this is the first fundamental practical step for the EU as such to acquire the status of a guarantor of liberal democracy within the bloc.”

As European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen prepares to deliver her annual state of the union speech on Wednesday, the bloc’s shock-and-awe approach seems to be having an effect, with European officials saying there are indications that Poland, at least, has been backing away from its hard stance.

The EU is hoping that, with its newfound financial leverage, it will be able to reverse its paltry record on disciplining rogue members, which has made it more complicated to stand up to China and support democratic values around the world. But with Hungary fully dug in, the bloc’s unity will be tested in a confrontation that could reshape the alliance in the coming years — either by effectively forcing member states accused of democratic backsliding to align themselves with its values or make them reconsider membership in the EU itself.

Anti-LGBTQ Push

It escalated this spring with growing frustration over how a loose alliance of illiberal countries were working to undercut ambitious EU plans, and things burst out into the open in June after Budapest passed a law that outlaws content for minors that is deemed to “promote homosexuality.”

A week later, EU leaders gathering in Brussels launched an almost unparalleled verbal assault directed at Orban. Luxembourg’s openly gay prime minister, Xavier Bettel, was one of the first to speak, describing how difficult it was to come out. Being gay isn’t a choice, Belgium’s Alexander De Croo told the Hungarian leader, but being homophobic is. Krisjanis Karins of Latvia appealed to Orban’s Christianity, saying if you believe in God you must be tolerant.

Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte landed a searing blow, telling Orban that if Hungary wasn’t willing to abide by the EU’s values, it should trigger Article 50, the mechanism for leaving the EU that has only been used once, by the U.K.

Orban told his colleagues he was astonished by their statements and that he felt like he was being attacked from all sides. The prime minister looked visibly taken aback after the onslaught as if he had been completely unaware of how unified and impassioned the debate would be.

But perhaps the most consequential statement came from Lofven, who reminded his colleagues that, for the first time, payments to member states from the bloc’s 1.8 trillion-euro ($2 trillion) budget — including from the new Covid recovery fund — could be withheld over rule-of-law violations. He added that Swedish taxpayers wouldn’t underwrite laws such as the one passed by Hungary.

When the EU passed a landmark budget and stimulus package in December to boost the recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic, a new mechanism was included that makes payouts conditional on adherence to the rule of law. And the Brussels-based commission, which had been eying a way to increase its geopolitical clout, is the gatekeeper of the stimulus fund — it has to approve each country’s recovery plan before any money can be disbursed.

The heated confrontation with Orban emboldened the commission, officials said, and gave it the latitude to strike a tougher stance with the two countries. Over the summer, the commission sent shockwaves through the bloc by postponing approval of Hungary’s and Poland’s recovery plans.

EU economic commissioner Paolo Gentiloni told members of the European Parliament earlier this month that the postponements were related to concerns over the rule of law, judicial independence and the primacy of EU law. He insisted the commission’s decision to pursue separate legal action against Hungary over the controversial anti-LGBTQ law was distinct.

But Hungary was surprised by the move, since officials had been penciling in a date for von der Leyen to visit Hungary to mark the plan’s approval, according to people familiar with the discussions. Government officials in Hungary, including Justice Minister Judit Varga, have repeatedly linked the delay with the legislation.

Billions at Stake

Hungary stands to miss out on 7.2 billion euros while Poland would forfeit 23.9 billion euros. The commission so far has disbursed about 50 billion euros to other countries from the stimulus package.

The EU’s scrutiny of its own member nations’ values comes as the bloc contemplates a more wide-ranging foreign policy. But at the June meeting, Belgium’s De Croo pointed out the irony that the summit’s conclusions were condemning human-rights violations in Ethiopia yet violations were being perpetrated within the bloc.

In the months ahead, Hungary and Poland can find their own ways of fighting back that could disrupt other EU ambitions. A year ago, both countries blocked the EU’s seven-year budget and the Covid recovery package was only salvaged following a delicately brokered compromise by Germany.

On numerous issues since the near-disastrous budget negotiations, Orban and Hungary have made things difficult — challenging the use of the words “gender equality” in EU documents and frustrating efforts to speak out for human rights in Hong Kong, according to another official. More recently, Hungary was the only EU country to not sign up to a statement about the crisis in Afghanistan.

The intransigence incensed lawmakers who criticize Orban for using the EU as a political punching bag for domestic purposes, but always being willing to accept the bloc’s money. Over the past seven years alone, Orban has teased out the loopholes to get Hungary a net 25 billion euros of EU funds. But the criticism appears to be having an effect.

Orban last weekend unexpectedly quashed an idea floated by some of his closest associates about the need to eventually consider an EU exit if Brussels kept up with its criticism. In Poland, the government pressured a senior ruling party lawmaker to backpedal on the same issue.

EU officials have said that a compromise with Poland over the rule-of-law issues could be possible, but they don’t expect a solution with Hungary at least until after the next national election, which could be in April.

“This is about the EU’s raison d’etre,” Tocci said. “The rule of law questions — whether it’s the judiciary or corruption or civil rights and hence LGBTQ — these are all fundamental pillars of liberal democracy.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.