Oct 18, 2022

Software Sprawl: Workers Flit Between Apps 1,200 Times a Day

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

Technology overload. IT bloat. Barnacle apps.

The problem goes by many names, but the story’s the same: Employees are swamped by an ever-expanding array of specialized software that’s made the workday a disjointed slog.

Workplace tools have never been popular — who enjoys filling out expense reports? — but when the pandemic hit, virtual communication and collaboration programs became critical for businesses. New employees got onboarded by one app, trained by another and surveyed by a third.

As Covid-19 wore on, concerns about burnout and record quitting rates prompted companies to add well-being and recognition programs. Rogue workers and teams brought in their own favorite tools as well. Apps upon apps, all with incessant notifications, cryptic passwords and byzantine protocols. And unlike your uncle’s Facebook posts, they’re not easily muted.

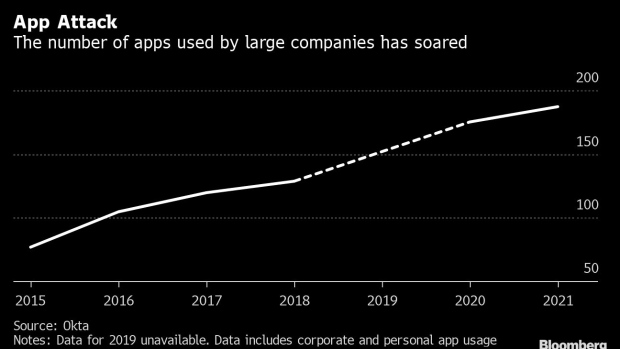

How bad is it? Companies deployed 89 different apps on average last year, up from 58 in 2015, according to Okta, a cloud software company. At large employers, that figure is now 187. Of those apps, close to 30% are duplicative or add no value, according to a survey of senior business leaders by WalkMe, an enterprise software provider.

A recent study of 20 teams across three big employers found that workers toggled between different apps and websites 1,200 times each day. That’s just under four hours a week, or roughly five weeks a year, spent hitting the Alt-Tab key. The researchers dubbed it the “toggling tax,” but it’s better known among psychologists as context switching — a habit that makes it hard to focus and, over time, stresses us out.

“Basically, how we work is itself a distraction,” said Rohan Narayana Murty, founder and chief technology officer at Soroco, which uses machine learning to map out how work gets done, and conducted the toggling study. “All day long, we just repeatedly switch between disparate applications.”

Frustrations with technology at big firms prompted 76 employees, on average, to leave last year, WalkMe’s survey found. “People only have a certain tolerance level and then they just check out,” said Bob Ellis, global head of the talent and organization practice at Infosys Consulting.

Scott Fingerhut, a longtime Silicon Valley marketing executive, has seen that firsthand over the years. “The hard thing,” he said, “is that most people don’t see it coming. You don’t get a notification for burnout.”App overload can strike any workplace. Natacha Arboleda is a hairdresser at Fox & Jane, a chain of about a dozen salons, mostly in New York City. The company uses one app for scheduling appointments, another for the stylists to chat with the office staff, and a third for HR functions like payroll and time off requests. Making matters worse, management has changed the HR app three times since Arboleda started there.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” she said. The apps can be time-consuming, especially when she gets logged out of one, forgets her password and has to ask a manager to help her get back in. The chat notifications are constant, and particularly distracting on her days off. But when she silences them, “I forget to turn them back on,” Arboleda said.

If a hair salon requires multiple apps, imagine a professional-services firm with dozens of clients, each with their own preferred programs that must be mastered. Steve Dinelli, who runs a digital marketing agency in Chicago, says the overload problem has hurt his company’s productivity.

“There are always messages going back and forth internally asking where different things are for different clients. Is it in a Google doc? Email? Dropbox? Slack? It could be anywhere.” And good luck trying to eliminate apps: “Clients will just find someone who will work the way they want.”

Technology overload is even influencing office design, and not necessarily for the better. MillerKnoll Inc., the furniture giant behind the ubiquitous Aeron chair, has been getting more requests lately for workstations that support two monitors rather than one. More apps, more screens.

The shifting nature of work after Covid-19 is not the only catalyst here. In the years before the pandemic, companies were moving from old-school mainframe software applications to cheaper cloud-based apps, also known as software as a service (SaaS). The $247 billion SaaS market is dominated by vendors like Salesforce Inc., Oracle Corp., SAP SE, Google and Microsoft Corp., whose Teams videoconferencing service now has more than 270 million active users, up from 20 million in 2019.

Cloud apps are easy to build, buy and roll out, which has led to what industry consultant Creative Strategies calls a “mix and match of workflows.”

For example, employees might prefer to do their video calls over Zoom, whose market share has nearly tripled since 2019. But during those calls, they’re also chatting on Slack and sharing documents using Microsoft’s Teams, which is neatly integrated with Word, PowerPoint and Excel. Some apps are just used by a few employees, while others are popular for a while, then get supplanted and fade into the background — the so-called barnacle apps. (Remember Skype?) More than half of IT professionals polled by cloud software maker Freshworks Inc. say they pay for SaaS stuff that their IT teams never even use.

Tori Paulman sees this happening every day. As a senior director analyst at Gartner Inc.’s employee experience technology group, she has to evaluate and recommend workplace software for clients that will make their jobs easier, not harder — what’s known in the consulting business as “human-centered IT strategies.” But her blunt assessment is that humans are barely in the periphery at the moment, much less the center.

“Technology,” she said, “has gone from the great enabler to the great inhibitor.” She relates horror stories where employees have to navigate five different apps just to start their day. Or her favorite: an HR leader who said employees were feeling fatigued by all these apps and asked if there was an app to fix it.

Don’t laugh: Often the only way to make sense of all this technology is to — you guessed it — add more technology. Project-management software vendors like Asana Inc., Atlassian Corp. and Monday.com promise clients that using their platforms can boost efficiency and reduce app clutter, and they have won over customers like Seismic Software Inc., which ditched a half-dozen programs recently to consolidate its workflows with Monday. San Diego-based Seismic, which makes software that helps sales teams, said the move is saving them time and money. But the company is still using separate apps to keep track of its business goals, and yet another to do employee surveys.

“There is still a bit of overlap in our systems,” said Linda Ho, Seismic’s chief people officer. What’s worse, even Ho — an executive in the software industry — said she doesn’t often see much to distinguish one app from another. “At some point, they all begin to be pretty much the same.”

Other business leaders have taken a scythe to their software sprawl. Prasad Ramakrishnan, the chief information officer at Freshworks, said he once had more than 800 apps inside his 1,300-person company. He’s now cut it down to just over 200, and his goal is to get to 150 eventually. (The firm now has more than 5,000 staffers.) One quick fix: The legal, finance and sales departments each used different document-management tools, and everyone had their own personal login — a huge security risk. Now, they all use Box Inc. Four videoconferencing apps were reduced to one. Every few months, he meets with his IT and finance team and finds new programs to cull. “It’s not a one-time project,” he said.

Don’t shed a tear for those pruned vendors, though. They’re hard at work coming up with brand-new workplace apps, like Microsoft’s Viva, an employee-focused platform that handles things like staff surveys, learning and goal tracking. Unilever Plc and PayPal Holdings Inc. employees are among its 10 million users, all of them hopeful that one more app will make all the difference.

A few startups are going even further by trying to replace Google’s Chrome and other ad-supported web browsers. One of them, a Bay Area firm called Sidekick — backed by venture capital titan Kleiner Perkins — is beta testing a business-focused browser that lets workers quickly move between apps and easily find any document or website. “Chrome will never evolve into something that’s built for work — that’s why you have thousands of tabs open all day,” Chief Executive Officer and co-founder Dmitry Pushkarev said. “Our idea was to build a much better work environment that’s not based on fatigue.”

Still, it’s often not clear if new approaches are adding to the clutter or reducing it. “Everyone thinks that just buying a tool will help you solve a problem,” said Ho, the HR chief. “This all happens with the best intentions.”

And that is the crux of the issue, said Fingerhut, the marketing executive: “It’s death by 1,000 good intentions.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.