Apr 8, 2020

Some of America’s Oil Refineries Face Closure Amid Demand Plunge

, Bloomberg News

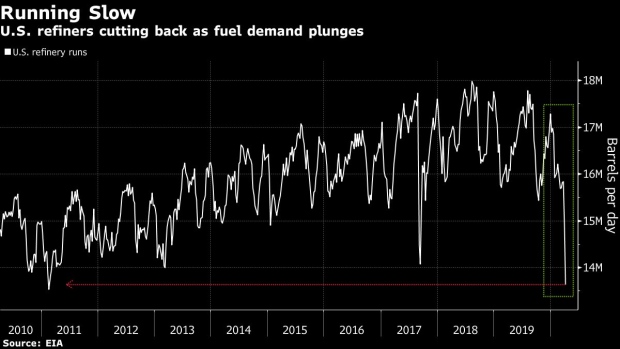

(Bloomberg) -- The next step for some U.S. refineries that have already cut way back may be a full stop.

Marathon Petroleum Corp. plans to idle its Gallup, New Mexico, refinery next week, according to a person familiar with the matter. It’s the first U.S. facility to shut as the coronavirus pandemic empties skies of passenger planes and the roads of cars.

It’s not likely to be the last. Major U.S. refiners, including Marathon, Valero Energy Corp. and Phillips 66, have lowered rates at their plants to or near minimum levels as storage tanks fill up with fuel they can’t sell. While that “minimum” level differs from company to company, and in fact from plant to plant, it’s seen typically somewhere around 60% to 65% of capacity. Below that, many facilities need to be idled.

“If after cutting rates to a minimum, refiners are still unable to move their products, they are faced with the prospect of completely shutting down,” said Andy Lipow, president of Lipow Oil Associates LLC in Houston.

Slowing down a refinery isn’t like turning down the fire on a gas range when the water threatens to boil over. A refinery is a complex web of interconnected units, so once the amount of crude being processed in the distillation unit falls too low, secondary units don’t have enough feedstock to keep running. Since many units operate under high pressure as well as high temperature, it becomes more difficult to maintain the proper conditions for operation.

“It’s complicated to keep the refinery in balance,” said Stephen Wolfe, head of crude oil at consultant Energy Aspects Ltd. “The rule of thumb for me was always 65% of the CDU. Below that, things get complicated. As you reduce rates, all the downstream operations have to be properly supplied, there are hydraulics limitations to how low you can go.”

Refiners have been forced to take drastic measures to reduce fuel supply with gasoline demand plunging by almost half and storage tanks filling up. Measures to slow the spread of Covid-19 have hit gasoline and jet fuel especially hard, sending wholesale prices in some markets below 20 cents a gallon and crushing profit margins.

While some complexes with multiple sets of crude stills and secondary units can shut one down, smaller plants have less flexibility. If the entire facility has to be idled, units may either be placed on circulation, where hot oil is circulated but no fuel is made, or shut down completely.

Minimum crude unit rates can range from 60% and up, depending on the type of oil being used, if there are multiple units and how much storage is available, said Lipow. “If you have multiple units, you could shut one down and run the others at varying rates.”

If a gasoline-making fluid catalytic cracker is shut, steam is lost that other units need to run. Shutting the cracker means finding a place for intermediate feedstocks like vacuum gasoil produced by the crude unit. An inland refinery can’t just put the intermediate products on a ship and send them elsewhere, but instead must store the products or send them away by more-expensive rail.

If only crude rates are cut, the conversion units like FCCs and hydrocrackers are starved of the intermediate feedstock they need to run and must be cut back also or feedstock has to be purchased to run them.

“There are more considerations than just saying we can shut this unit down and there is no more ancillary impacts,” said Lipow.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.