Jun 30, 2022

Spotify's billion-dollar bet on podcasting has yet to pay off

, Bloomberg News

Surprising strength in earnings given everything that went under Q1: Strategist

Dawn Ostroff rose to the top of the TV industry in the 2000s by developing deliciously addictive shows such as America’s Next Top Model and Gossip Girl. A former local news reporter, she’s credited her success to knowing what young people like. “Being at the forefront of ‘what’s next’ has always driven me,” she told the news site of Florida International University, her alma mater, in 2020. But after more than three decades in TV, Ostroff saw that a generation raised on the internet had forsaken cable for apps like TikTok, YouTube, and Instagram. She took the job as Spotify’s chief content officer in 2018 to make a new kind of hit.

Spotify Technology SA was just starting to build its podcasting business when Ostroff joined, and it needed to find a splashy way to attract listeners. Although she had no background in podcasting—or music, for that matter—her time in TV taught her how to talk to talent. Over the next four years, Ostroff spent more than US$1 billion on the business, licensing shows, buying production studios, and signing exclusive deals with celebrities, including the Obamas, Kim Kardashian, and Prince Harry and Meghan Markle.

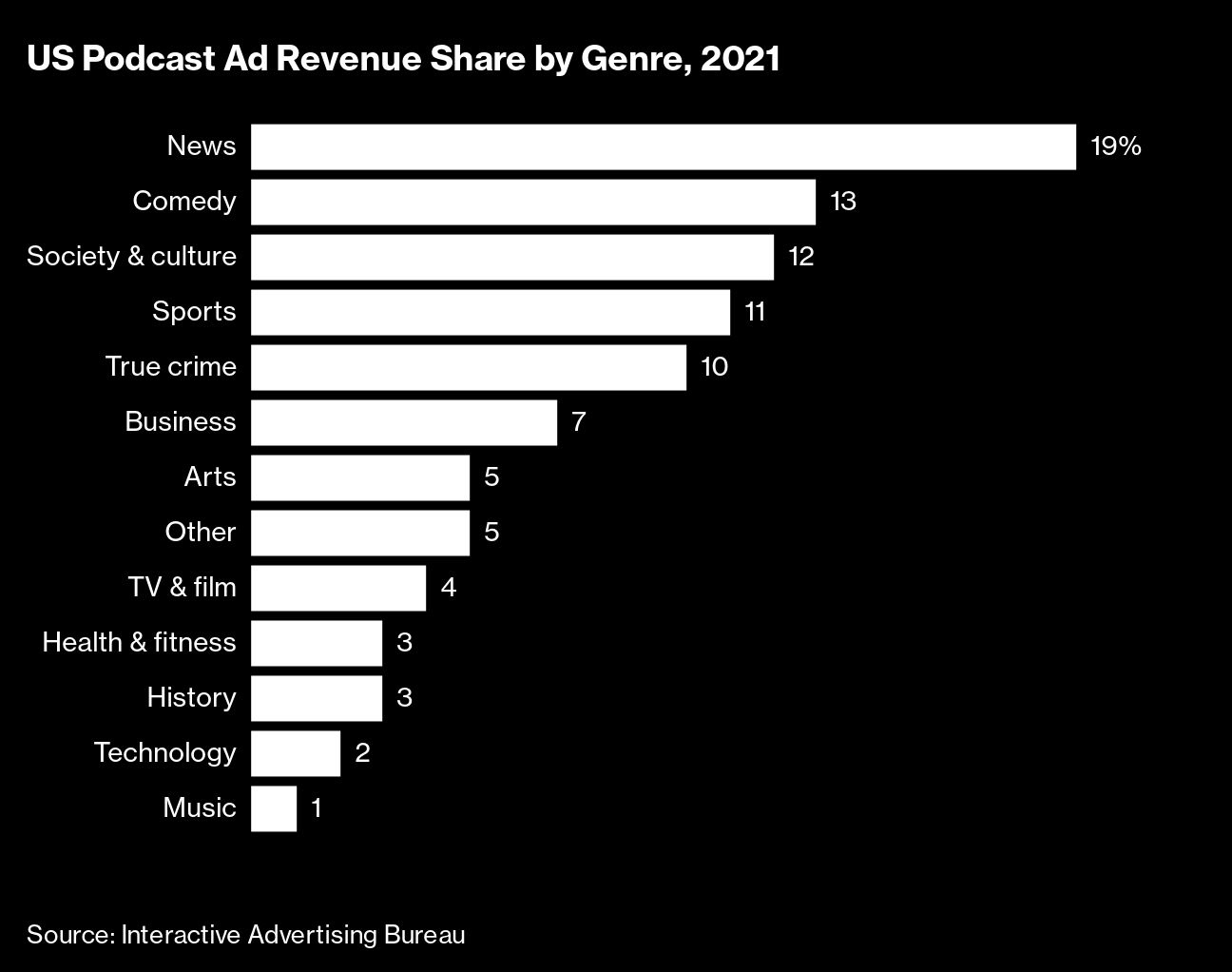

Last year, Ostroff’s research and data team asked a question that many at Spotify already knew the answer to: Had any of this spending yielded a major new hit? The team produced a report that basically said no, according to five current and former employees who didn’t want to be named discussing internal business. Spotify evaluated how well shows did based on listenership, their traction on social media, and if they attracted new fans to the service, among other criteria. The team, the employees say, identified two groundbreaking hits—neither of which Spotify produced: Serial, the true crime drama that introduced many to the format (and is now owned by the New York Times), and The Joe Rogan Experience, a talk show from the former host of Fear Factor. (Rogan’s show is currently exclusive to Spotify.) A couple of dozen shows were classified as lesser hits.

The report frustrated people in Ostroff’s orbit, according to the employees, who described the findings to Bloomberg Businessweek. Sure, Spotify hadn’t produced a show that penetrated the culture as Serial had, but its studios are responsible for many popular podcasts. One of those studios, Parcast, is behind Call Her Daddy, a show hosted by Alex Cooper about relationships and sex that’s one of the 10 most popular podcasts in the US, according to Edison Research. Another, the Ringer, produces a network of beloved sports and pop culture shows led by Bill Simmons’s eponymous podcast. (I contribute to a Ringer podcast, The Town, about the business of Hollywood.) The frustration stemmed in part from the R&D team measuring podcasts against TV shows such as Lost that drew almost 20 million viewers a night in its heyday. Call Her Daddy has about 3 million listeners—known collectively as the Daddy Gang—according to the Los Angeles Times. (Ostroff declined to comment for this story.)

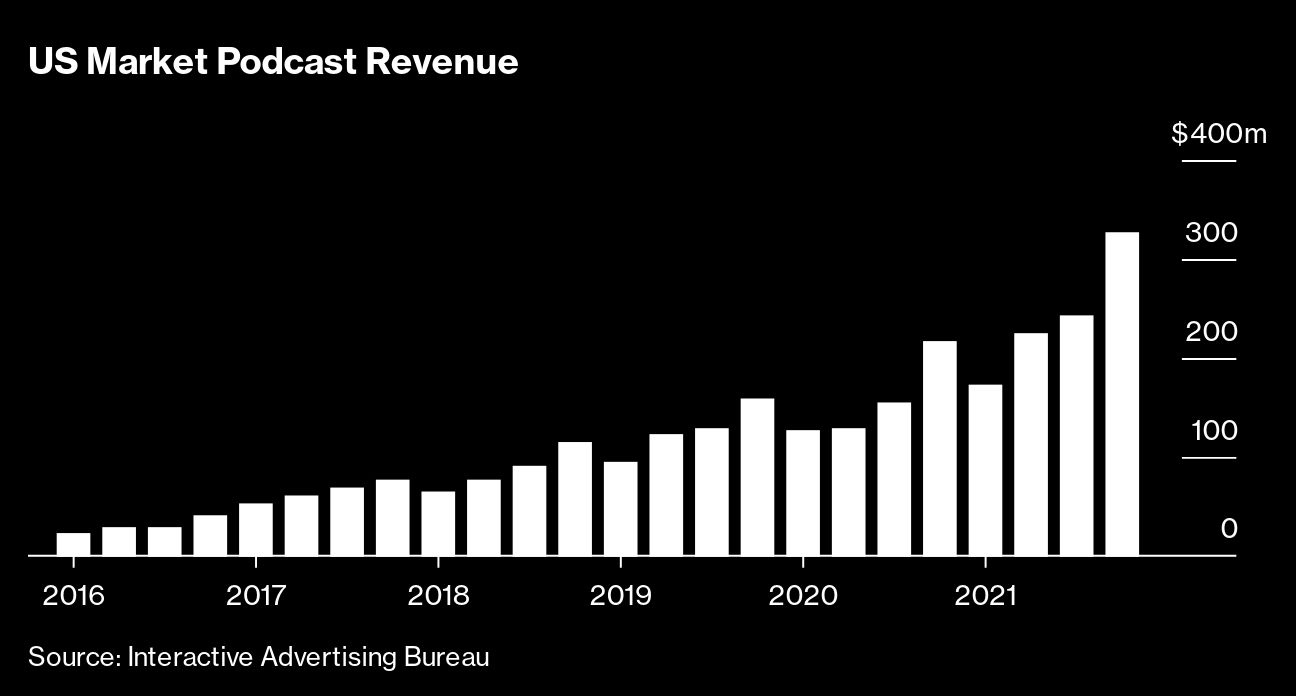

Spotify moved into podcasting to free itself from the unprofitable and competitive business of music streaming. The company’s deals with record labels require it to pay them more than 70 per cent of every dollar that comes in, which is why Wall Street has long doubted the business model. Podcasting offers Spotify exclusive material that forces other tech giants to carry its service—and creates a revenue stream the music labels can’t touch. Yet despite all of Spotify’s spending on podcasting, it accounted for only 7 per cent of total listening hours in the first quarter of 2022 and 2 per cent of revenue last year, the company announced in June. Rogan’s show, the service’s most popular and controversial, has caused Spotify one public-relations headache after another.

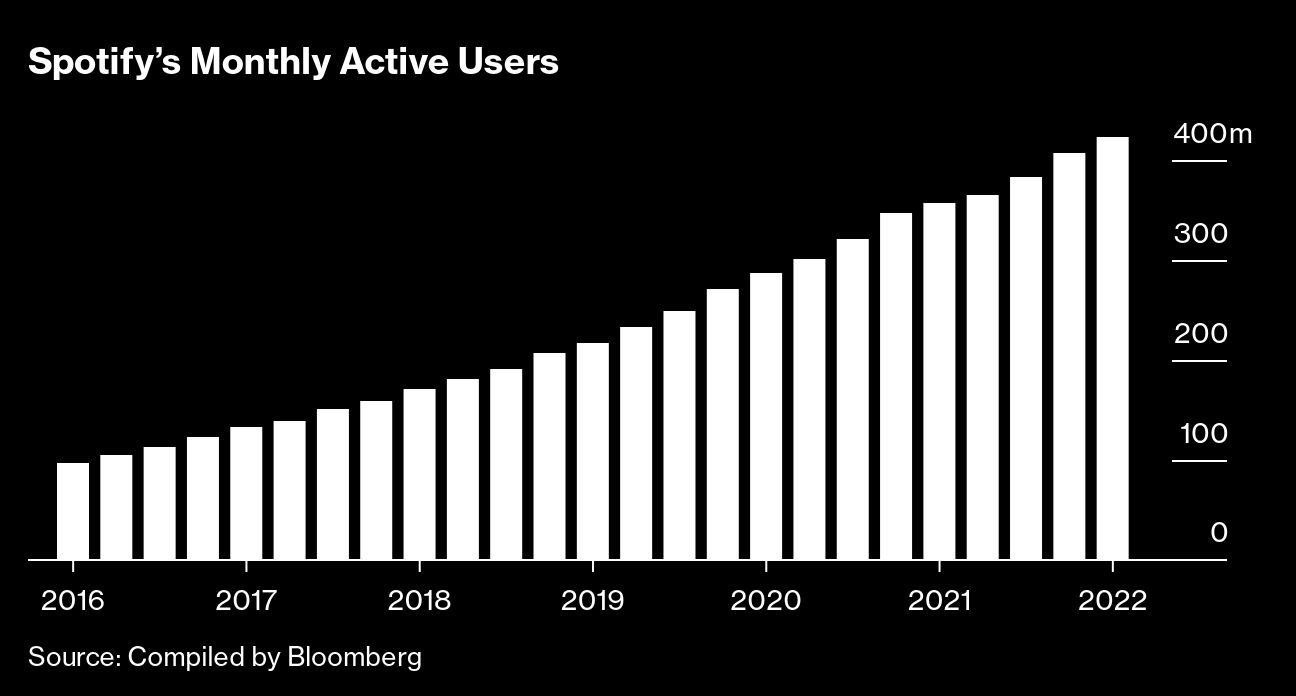

It’s too early to call the strategy a failure. With more than 420 million users and about 182 million paid subscribers, Spotify is the largest audio service in the world. It’s the dominant platform in music streaming and has supplanted Apple as the most popular way people listen to podcasts in many markets. But the company has struggled to convince Wall Street that its spending spree has been worth it. Spotify’s stock price has slipped 72 per cent from its February 2021 peak, plunging from about US$365 to roughly US$101 a share as of June 21.

Daniel Ek, Spotify’s chief executive officer, says the selloff is shortsighted and ignores the company’s strong fundamentals. Losses from podcasting will begin to tail off this year as ad sales rise and investment growth slows, Spotify said earlier this month, and eventually podcasting will have better profit margins than music. The company’s consistent user growth has attracted marketers, with total ad sales topping €1.2 billion (about US$1.3 billion) last year, more than double what they were in 2018.

Spotify now sees advertising, long an afterthought to the “freemium” subscription model, as a big part of its future. After a couple of years touting its high-profile original series to draw in listeners and talent, the company is shifting its messaging, positioning itself as a user-generated playground for audio, like what YouTube is for video. Spotify hosts 4 million podcasts, and it wants to host millions more. So in addition to offering up top-tier talent, it aims to make it easier for regular people sitting in their bedrooms to make a living by talking. Executives say they just need time to let the strategy play out.

Spotify is “throwing a bunch of stuff at the wall,” says Nick Quah, a critic and founder of industry newsletter Hot Pod. “They have quite a bit to go in terms of constructing a mature, functioning, coherent machine. The question is whether they’ll be able to do that before investors lose patience.”

Courtney Holt kept coming back to Joe Rogan. Holt had joined the company a year before Ostroff’s arrival to build a business for Spotify beyond music. With Ostroff and Ek, Holt settled on podcasting as the way forward. Spotify customers were already listening to music, so it was reasonable to think they’d toggle from Drake to Dirty John, a true crime podcast. Holt pitched creators on the idea of Spotify as an alternative to Apple. They could convert Spotify’s music fans into listeners of their programs, and get help selling ads. (Apple Inc. leaves this to creators.) By 2019, more than 400,000 podcasts had been uploaded to Spotify.

Rogan didn’t need Spotify. The Joe Rogan Experience, with the largest audience in podcasting, was doing fine without it. But in late 2019, Holt ramped up efforts to reach him. The Spotify executive knew that it was easier to acquire an audience than build one from scratch, as he’d done successfully when he bought the rights to The Joe Budden Podcast, and fans of Budden followed the rapper-turned-podcaster to his new home. He’d been less successful developing an audience for comedian Amy Schumer. Eager to find more shows to lure listeners, Holt and Ostroff went shopping. They purchased Parcast, best known for true crime; the Ringer; and Gimlet Media Inc., the so-called HBO of podcasting because of its award-winning nonfiction series such as Reply All. Spotify couldn’t buy Rogan’s show—he wasn’t selling—so it offered him more than US$100 million for the exclusive rights.

Rogan wanted Spotify’s money, but he didn’t want to appear muzzled by a corporation in exchange for cash, say three executives who worked on the deal who weren’t authorized to discuss details. Rogan’s millions of fans, mostly young White men, worship him as a contrarian free thinker; deferring to corporate sensitivities would be bad for his brand. Rogan demanded complete creative control and insisted on an expansive morals clause that would let him say almost anything without fear of retribution, say the execs. (Rogan didn’t respond to a request for comment.) Some questioned if he was worth the risk. He routinely hosts controversial figures, such as conspiracy theorist Alex Jones. The execs debated if Spotify could replicate Rogan’s audience with four or five other hosts. The short answer was no. The company went along with his demands.

Spotify’s stock jumped about 8 per cent the day it announced the Rogan deal in May 2020. Investors had been lukewarm on the company since it went public in April 2018, but Rogan changed perceptions. When selling itself to investors before its initial public offering, Spotify had compared itself to Netflix Inc., another streaming service that had moved consumers from analog to the internet. And just as Netflix transitioned from hosting other production companies’ TV shows to making its own, Spotify was now attempting to transition from hosting other companies’ audio to producing its own (or securing exclusive rights). Many investors viewed Rogan’s show as Spotify’s House of Cards, the series that put Netflix on the map. The Joe Rogan Experience made its debut on Spotify in September 2020 and went exclusive in December. It’s been the service’s top podcast ever since.

Buoyed by the Rogan deal, Holt and Ostroff set out to corner the market on talent. They secured exclusive rights to Dax Shepard’s celebrity talk show, Armchair Expert, and, eventually, Call Her Daddy, for which it paid upwards of US$60 million, say two people familiar with the terms who weren’t authorized to discuss them. The pace and size of the deals stunned the industry, upended the economics of the podcasting business, and transformed Spotify from music streamer to “multichannel tech-media company,” says Quah. Like reality TV, popular talk shows such as The Bill Simmons Podcast and Call Her Daddy cost almost nothing to produce; the hosts sit in a studio and interview guests. (The budgets for scripted projects range from a few hundred thousand dollars to several million if top-tier talent is involved.) But Spotify was now paying popular hosts millions of dollars a year.

Hollywood talent agencies, Madison Avenue advertisers, and Wall Street investors all gave the company another look. By the start of 2021, about 25 per cent of Spotify users, or roughly 86 million people, were listening to podcasts on the service. The stock traded at more than US$300 a share, valuing the company at over US$50 billion. Wall Street’s positive response to Spotify’s spending prompted Amazon.com Inc. and Sirius XM Holdings Inc. to join the fray. Amazon paid US$300 million for the studio Wondery and nearly US$80 million for distribution and ad sales rights to SmartLess, a talk show hosted by actors Will Arnett, Jason Bateman, and Sean Hayes. Sirius XM acquired the podcast app Stitcher for more than US$300 million and the production company 99 per cent Invisible, with a podcast of the same name, for an undisclosed sum.

Spotify’s most popular original show of 2020 was The Michelle Obama Podcast, a limited series of interviews hosted by the former first lady that attracted hundreds of thousands of new listeners. Spotify had announced its deal with the Obamas’ production company, Higher Ground, in June 2019. The signing seemed like a coup.

The deal with the Obamas was the first in a series of agreements with some of the world’s biggest celebrities. While Holt had been a proponent of acquiring existing studios and exclusive rights, Ostroff championed arrangements with famous people who had little experience making podcasts. She secured deals with Kim Kardashian; social media influencer Addison Rae; Prince Harry and Meghan Markle; and filmmakers Ava DuVernay, Jordan Peele, and the Russo brothers, best known for directing Marvel movies. No one had much experience in audio, but Ostroff figured that good storytelling worked in any medium.

While Ostroff lured in the big fish, wrangling this talent fell to Holt and his deputies, according to more than a half-dozen producers and podcasters who worked with Spotify. Holt had little experience as a creative executive, having spent most of his career on the business side of music and media companies. Ostroff had hired another TV exec, Liz Gateley, to oversee development of new shows, but she shifted to an advisory role and left after 18 months. (She’s since returned in a similar capacity.) Holt created Studio 4 to handle projects that didn’t naturally fit with Gimlet, Parcast, or the Ringer. When the Obamas, say, wanted project approval, Holt was often the one saying yes or no.

It didn’t take long for relations between Spotify and its partners to sour, say the producers and podcasters. Higher Ground produced Tell Them I Am, an interview program featuring Muslim voices, and The Big Hit Show, a reported podcast about pop culture. But Spotify rejected several pitches from Higher Ground, including some that seemed to the Obamas like a slam dunk. It took months, for example, to get approval on a Stevie Wonder project produced by Questlove, the Grammy-nominated musician. (It’s likely to happen.) The Obamas started their company to elevate underrepresented voices. But Spotify didn’t see commercial potential in most of the ideas—they wanted two of the most famous people on Earth behind the mic.

Most successful podcasts upload new episodes every week, often more than once. But the Obamas weren’t going to spend their post-presidency grinding it out in a recording studio. They’ve produced movies and TV shows for Netflix, none of which required being so hands-on. The first of what would ultimately be nine episodes of Michelle’s podcast featured an interview with her husband. The former president recorded a conversation with Bruce Springsteen—and then that was it. All told, the Obamas recorded about 15 hours of audio for Spotify. Technically, they fulfilled their deal, but their output was less than what Rogan releases in a couple of weeks.

At least the Obamas produced some shows. DuVernay never did, and the deal with the Russos was never officially signed. Archewell Audio, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex’s studio, plans to release its first series, Archetype, later this summer or in early fall; Markle will interview experts about stereotypes that have held back women. Kardashian’s first show, on criminal justice, is expected later this year, as is Peele’s, which is in the horror-thriller category. Simmons argues that the investment in celebrity-driven shows has attracted millions of new listeners. Spotify needed to steal market share from Apple, and the only way to do so was to make noise. “Sometimes you have to learn the hard way. You do a deal with a production company, and it turns out they don’t know how to produce anything,” he says. “There have been a couple misses. There have been a lot of hits, too.”

By the middle of last year, Ostroff decided it was time for a change. The podcast business was growing, yet Wall Street was questioning the results of corporate investments. She wanted someone new to lead Spotify’s podcast studios. (Holt would now oversee live audio and other new projects.) She hired Julie McNamara in September 2021 from Paramount, where she oversaw original programming for streaming service Paramount+. McNamara shuttered Holt’s catch-all, Studio 4, and has overhauled the way Spotify develops and produces podcasts.

She created a central team of creative executives to help pick and shepherd projects. Partners had previously complained about an unclear chain of command and a lack of continuity in the development process. “When you have a partnership with people that haven’t done audio before but are expert creatives, having infrastructure is really important,” she says.

Many of the executives who built Spotify’s podcasting business have left the company. Lydia Polgreen, who joined Spotify to run Gimlet after a long career in print journalism, returned to the New York Times. Matt Lieber, Gimlet’s co-founder, has said he will leave later this year. Holt, marginalized following McNamara’s hiring, resigned. The Obamas signed a new deal with Amazon’s Audible Inc. on June 21.

At the same time Rogan was boosting Spotify’s share price, he emerged as a leading skeptic of COVID-19 vaccines. After listening to him peddle skepticism for more than a year, hundreds of doctors signed a letter in January 2022 rebuking him and Spotify for endangering lives. Rock star Neil Young, who had polio as a kid, threatened to pull his music from Spotify if the company didn’t cut ties. Spotify declined, and Young followed through on his threat, inspiring Joni Mitchell, Nils Lofgren, and several others to follow. After a few days of scandal, Rogan vowed to do more research before talking about certain topics and to balance out the more controversial viewpoints he aired.

As the controversy was ebbing, a video circulated online documenting the many times Rogan used racial slurs on his podcast. He apologized and said his words had been taken out of context. But the comments weren’t a shock to many at Spotify. The company had conducted a review of Rogan’s back catalog while doing the deal and identified several episodes that violated its content guidelines, which ban inciting violence, promoting terrorism, and targeting individuals for abuse and harassment. (As a music service that offers millions of rap and hip-hop songs, Spotify has no rules against the use of certain racial slurs.) Rogan elected not to upload those episodes to Spotify, which would have taken them down. There were several others that didn’t violate Spotify’s guidelines but did contain potentially problematic material regarding race, sex, and other topics. The company could only ask Rogan not to upload those episodes. He did so anyway.

The controversy damaged Spotify’s relationships with talent. DuVernay ended her deal that month. Still, it didn’t lead to mass defections of musicians, podcasters, or users. Ek said he disagreed with many things Rogan has said, but he also declined to take action against him. “I do not believe that silencing Joe is the answer,” he said at the time. (Spotify declined to make Ek available for an interview.)

Throughout the scandal, Ek portrayed Rogan as just another creator, as if Spotify hadn’t paid him more than US$100 million. That may be disingenuous, but it underscores that Ek, despite funding hundreds of shows, views his company as a platform, not a programmer. Producing original podcasts helps Spotify differentiate itself and draws in users and advertisers. But the long-term plan for the company is not to produce thousands of finely crafted original series. It’s to host millions of shows and hope some of them become as big, or nearly as big, as Rogan’s.

YouTube built a US$30 billion ad business by catering to almost every video creator in the world. Spotify wants to do the same for audio, with the goal of hosting 50 million creators by 2025. When it acquired Gimlet and Parcast, it also bought a distributor, Anchor, to more easily let people upload their podcasts. And it acquired a company called Megaphone to help creators sell ads.

Earlier this year, Spotify announced a new structure for its podcasting business: McNamara will supervise original programming, while Parcast founder Max Cutler will oversee creators, managing relationships with the millions of shows that are produced by third parties.

McNamara has already scored her first big hit with Batman Unburied, a scripted podcast based on the DC Comics character. The show supplanted Rogan’s atop Spotify’s charts for a couple of weeks. Spotify will soon announce a slate of programs with sportswriter Jemele Hill, who has her own, independent podcast network. McNamara will also oversee video, which Spotify sees as an opportunity. A growing number of Rogan and Call Her Daddy fans watch—instead of just listen to—those podcasts on Spotify. And video dwarfs audio as a business. Netflix’s revenue is three times the size of Spotify’s, despite comparable subscriber bases.

As Spotify’s share price plunged to record lows in June, the company hosted an investor day to alter the narrative. Yes, Ek said, even as Spotify’s users, sales, and subscriber base have grown, its margins haven’t improved. But that’s because Spotify is investing in projects that will bear fruit in the future. “We saw the potential to be much more than just a music company,” he said.

For all the issues Spotify has, everyone in the podcasting industry agrees that it’s on track to become the dominant player everywhere, thanks largely to brute force: It’s invested the most money in new shows, especially abroad, as well as in the technology to capture ad dollars. As long as Apple doesn’t sell ads and fund original programming, Spotify will ultimately be the big winner.

How big the win will be is another matter. Spotify has built a multibillion-dollar subscription business without turning a profit. It says it can generate US$100 billion in sales by diversifying further into podcasts, as well as other audio businesses. Ad sales now account for more than 10 per cent of total revenue. There’s still more than US$10 billion in ad sales captured annually by AM/FM radio, and billions of dollars more in the audiobook business—most of which benefits Audible. Spotify is convinced more of that business will come its way; after all, only 14 per cent of podcasts currently earn the company any money. “In three years, Spotify has gone from basically zero to being the market leader in the US and a bunch of other markets,” McNamara says of podcasting. “It is very challenging to lay the track while the train is running.”