May 22, 2019

Steelmaking History Counts for Little as Fresh Crisis Hits U.K.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- In just two weeks, the steelmaking industry in Britain, a country that once supplied almost half the world, has been thrown back into crisis.

The U.K. only has two primary steelmaking sites -- where giant blast furnaces swallow iron ore and coking coal. One site makes flat steel for cars and appliances and the other produces long products for rail and construction. Both face an uncertain future.

British Steel, owned by private equity group Greybull Capital LLP, is desperately seeking a bailout from the U.K. government to avoid falling into administration. Tata Steel Ltd.’s Port Talbot is more secure, but after the collapse of merger talks with Thyssenkrupp AG, its long-term viability looks increasingly threatened.

The twin problems couldn’t come at a worse time for U.K. politicians. With European elections this week and an exit deal still up in the air, a collapse of British Steel and the possible loss of 5,000 jobs in the manufacturing heartland would heap criticism on how Brexit uncertainty is crippling key British industries.

Business Minister Andrew Stephenson told Parliament on Tuesday that the government will do all it can to save the plant, but it’s constrained by rules governing state aid. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn called for the U.K. to take a public stake in the company if a deal can’t be reached.

“Britain’s proud steel industry has a major role to play in ushering in a Green Industrial Revolution, securing British manufacturing for a sustainable, green future,” Corbyn said. “It needs support, not a death warrant.”

British Steel has asked the government for about 30 million pounds ($38 million) and has warned it will fall into administration without the support, according to a person familiar with the matter who asked not to be identified.

“The British Steel Group has faced various trading challenges recently,” the company said in a statement on Tuesday. “In response to this, we have been working closely with our stakeholders to consider the different funding options.”

There are other problems. British producers usually pay more for power than European rivals and many plants have suffered from lower investment over the previous decades, leaving them behind the rest of the industry.

Europe’s steel market is also under wider pressure, especially in the flat product market that’s been hit by weak demand from carmakers and high imports from Turkey. ArcelorMittal, the region’s biggest producer, has said it expects demand to contract in Europe this year and lobby group Eurofer warned that steelmakers are on the cusp of a severe crisis.

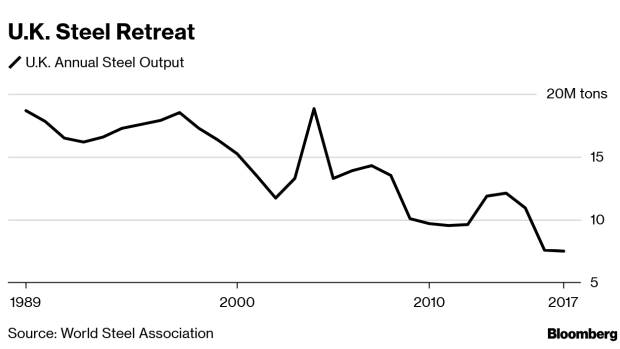

In its Victorian heyday, Britain produced about 40% of the world’s steel. It was overtaken by the U.S. at the start of World War I. In the 1970s and 1980s, inefficient and outdated plants led to production falling 64% to less than 10 million tons, and the country’s output slipped below France, Italy and Belgium.

Today, the U.K. produces 7.5 million tons a year, about 0.4% of global production.

Tata has said it remains committed to Port Talbot, but the plant needs to generate more money to guarantee its future. It expects to return to profit this year, despite the ugly steel outlook.

What happens next to Britain’s steel industry is an open question. It’s survived bigger threats in the past, like the 2016 commodity crisis when Tata put all its British assets up for sale.

“We must remember the steel industry is an enduring, resilient one,” said Gareth Stace, head of lobby group U.K. Steel. “We have been the bedrock of the U.K.’s industrial landscape for 150 years since we pioneered mass steel production techniques.”

“There is no reason why this should not continue to be the case for many years to come.”

--With assistance from Alex Morales.

To contact the reporter on this story: Thomas Biesheuvel in London at tbiesheuvel@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Lynn Thomasson at lthomasson@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.