Nov 26, 2021

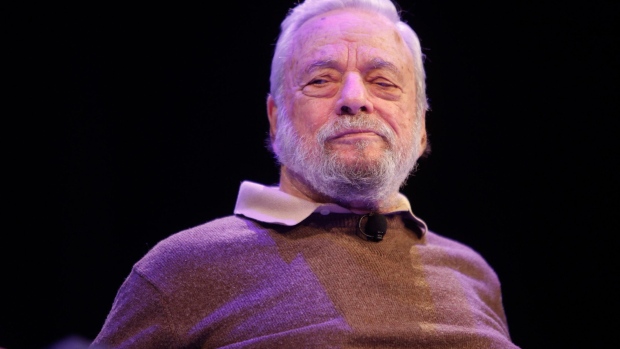

Stephen Sondheim, Tony-Winning Broadway Innovator, Dies at 91

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Stephen Sondheim, whose quick-witted lyrics made Broadway audiences sit up and listen in the 1950s and whose cerebral, ground-breaking shows from “Company” in 1970 to “Merrily We Roll Along” more than a decade later thrust the American musical into the modern era, has died. He was 91.

His death was announced by F. Richard Pappas, his lawyer and friend, according to the New York Times, saying it was “sudden.” Sondheim had a Thanksgiving dinner with friends the day before, the paper said. Pappas couldn’t be immediately reached in his office in Austin, Texas.

Coming of age between the post-World War II era dominated on Broadway by Rodgers and Hammerstein and the post-Vietnam British invasion epitomized by Andrew Lloyd Webber, Sondheim created shows around urban sophisticates, a murderous barber and single-minded obsessives.

Broadway productions for which he was both composer and lyricist that won Tony awards for best musical included “Passion,” “Sweeney Todd,” and “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum.” His “Sunday in the Park with George” won the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

A student of the composer Milton Babbitt and protege of the romantic lyricist Oscar Hammerstein, Sondheim wrote shows that shimmered -- and sometimes shivered -- in the crawlspace between sentiment and existentialism. He was, as one of his most famous lyrics put it, the quintessential “Broadway baby,” able to please an audience with rousing anthems and plangent ballads.

“One of the brightest lights of Broadway is dark tonight,” New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio said in a tweet, calling Sondheim a “legend.”

Innovative Force

He was also Broadway’s most fearless innovator, constantly staking out new musical territory, whether or not the audience could be cajoled into joining him on the journey.

Neither as popular as Rodgers and Hammerstein nor the Gershwins, and not a box-office sensation like his younger contemporary, Lloyd Webber, Sondheim nonetheless set the standard for contemporary American musicals.

“Send in the Clowns,” from 1973 Tony winner “A Little Night Music,” was arguably the only standard in his vast catalog of songs. Renditions by Judy Collins and Frank Sinatra became hits.

Others, from “The Ladies Who Lunch” (“Company”) to “I’m Still Here” (“Follies”) and “Move On” (“Sunday in the Park with George”) became mainstays of cabaret singers.

Sondheim also wrote songs for several films, including “Reds,” “Dick Tracy” and “The Birdcage.”

West Side Story

Trained as a composer, he earned his first Broadway billing as lyricist for 1957’s “West Side Story.” His far more experienced collaborators were Leonard Bernstein, who composed the music; Arthur Laurents, who wrote the book; and Jerome Robbins, who staged and choreographed the landmark show.

Two years later, he collaborated with composer Jule Styne on “Gypsy” and the result was another high point in the pantheon of Broadway musicals.

With “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum,” Sondheim finally got billing as both composer and lyricist. A giddy travesty of comedies by the Roman playwright Plautus that was also staged by Robbins, the hit starred Zero Mostel as a slave desperate for freedom and sex, not necessarily in that order.

But it was Sondheim’s decade-long partnership with producer-turned-director Hal Prince, beginning in 1970 with the musical comedy “Company,” that solidified his place in the first rank of Broadway visionaries.

Based on writer George Furth’s stories about a swinging single and the married couples in his life, “Company” lacked a conventional plot. Instead, it focused on the ambivalence of Bobby, the central character, as he observes the marital discord all around him.

Critics Disagree

Paradoxically, “Company” also first saw the critical divide between those who found Sondheim challenging and insightful and those who dismissed him as too intellectual for a general audience.

Stephen Joshua Sondheim was born March 22, 1930, the son of Herbert Sondheim, a dress manufacturer, and his chief designer, the former Janet Fox. They lived on Manhattan’s Central Park West, until the parents divorced when he was 10.

As a youth, Sondheim became friendly with Jamie Hammerstein. In Jamie’s father, Oscar, he found a lifelong mentor. Oscar Hammerstein’s principles of lyric writing would later take on biblical significance for Sondheim even as he rebelled against the form that Hammerstein and his last great partner, composer Richard Rodgers, had themselves redefined for Broadway audiences.

‘Serious’ Composer

Sondheim briefly attended the New York Military Academy in Cornwall, New York. At Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts, from which he graduated in 1950, he began studying music in earnest. Babbitt, who taught at Princeton University, later took him on as a private pupil even though he knew Sondheim wasn’t interested in becoming a “serious” composer.

Only Hal Prince was as important as Hammerstein in focusing Sondheim’s vision. Both were interested in offbeat subjects. But where Sondheim saw private little sagas, Prince saw major statements.

The sometimes fitful merging of those two intellects and approaches resulted in a new kind of “concept musical,” beginning with “Company” and extending through “Follies,” “A Little Night Music,” “Pacific Overtures,” “Sweeney Todd” and “Merrily We Roll Along.”

New Collaborator

The commercial failure of 1981’s “Merrily We Roll Along” led to a split with Prince, who died in 2019. Sondheim’s next important collaborator was James Lapine, a young director and writer influenced by Jungian psychology and the influence of dreams.

Together they wrote “Sunday in the Park with George,” in which Sondheim acknowledged the isolation of the artistic process by telling the story of the French Pointillist painter Georges Seurat, and his muse, Marie.

They also collaborated on 1987’s “Into the Woods,” a freewheeling mash of fairy tales that became one of Sondheim’s biggest box-office successes.

“Side By Side By Sondheim” and “Putting It Together” were just two of the many shows built around Sondheim’s songs. Although he was always working on new material, Sondheim spent his last decades encouraging the growth of young artists, founding the Young Playwrights Festival.

His last new Broadway musical, also written with Lapine, was 1994’s “Passion,” based on the novel “Fosca” by I.U. Tarchetti and the subsequent Ettore Scola film, “Passione d’Amore.” The musical concerned a handsome military officer with whom a sickly woman falls all-consumingly in love.

For decades, Sondheim had stood accused of a certain aloofness and ambivalence toward love that derived from his solitariness, his homosexuality, his perfectionism and his literary conceits. “Passion” was an attempt to address that criticism.

But like so many of his shows, “Passion” left the critics, and the public, deeply divided. Despite winning the Tony, it struggled for a few months and closed without earning back its production costs.

Yet those who saw it will never forget it. That seemed to be Sondheim’s fate.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.