May 13, 2019

Stock strategist who nailed 2018 says recession bell is ringing

, Bloomberg News

Markets still pricing in risk from prolonged China-U.S. trade tiff: UBS' Parker

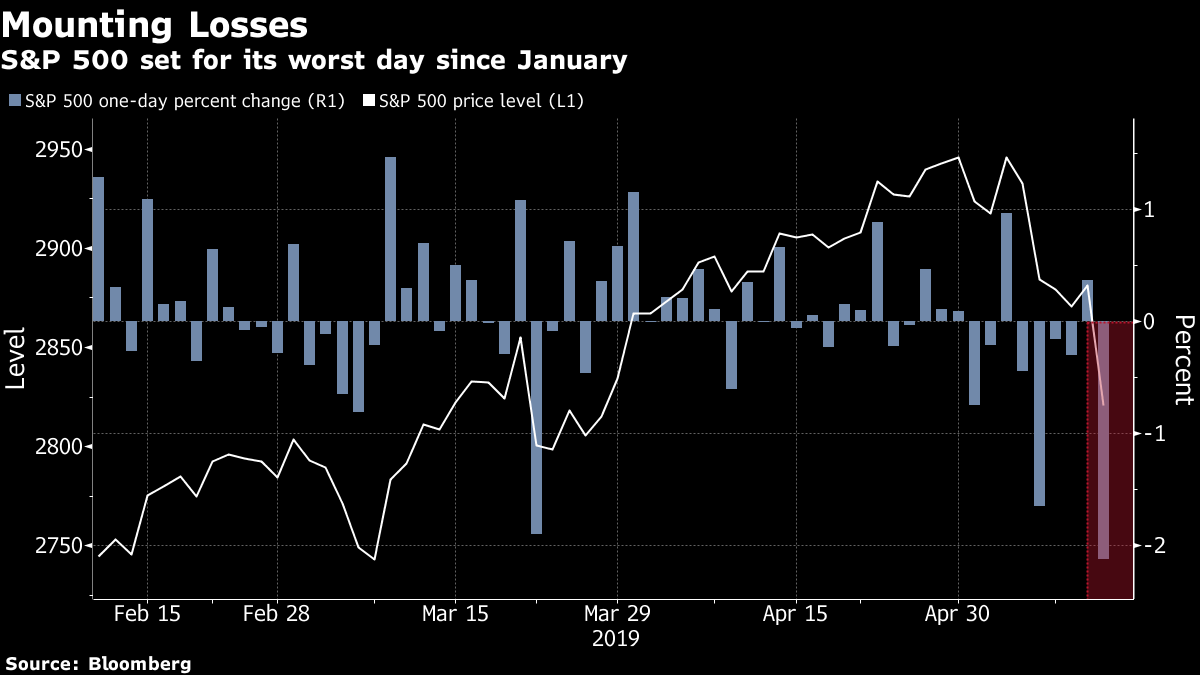

After a tumultuous week ended on an up note, it seemed U.S. stocks might escape the trade spat with only bruises. Then came Monday, when the biggest selloff in four months more than doubled last week's damage.

What changed? The reality of a potential impasse took hold. Maybe the U.S. and China won't come to terms. Maybe the stock market won't be able to right its ship. And maybe the consequences will be too much for the economy.

It’s a minority view, to be sure, but for Mike Wilson, Morgan Stanley’s chief equity strategist, the escalation has increased the likelihood for a prolonged economic downturn — the most reliable killer of bull markets. JPMorgan Chase & Co’s head of cross asset fundamental strategy, John Normand, warned that stocks could fall another 10 per cent.

“The risk of an economic downturn has increased substantially,” Wilson said in a note to clients Monday. “While last week’s correction helped move the risk-reward closer to balanced, we think there is likely more downside than upside based on our high conviction view that earnings expectations remain too high by 5-10%.”

After stocks closed, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston President Eric Rosengren said it’s too soon to say what the escalation means for the economy, but it could deliver a lasting boost to inflation while the reaction of financial markets also matters.

“To the extent we get sharp movements in financial markets that have wealth effects and other effects, those are pretty unpredictable, so it does become important how much the market reacts over time to the announcements of tariffs,” he said in an interview with Bloomberg News.

To be sure, Wall Street models have flashed recession signals before and the economy has been fine. Corrections like the one at the end of last year have occurred five other times since the bull market began in 2009, and no recessions materialized. Still, virtually every economic downturn in the last century was accompanied or preceded by a bear market.

After a weekend of back-and-forth trade squabbling, anxiety that the trade spat will sap corporate profits grew Monday after China retaliated with punitive tariffs on some American goods. The S&P 500 sank 2.4 per cent in the biggest rout in four months, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average lost more than 600 points. Apple Inc. (AAPL.O), which relies on China for 20 per cent of its revenue, sank 5.8 per cent.

Wilson, one of the biggest equity bears on Wall Street and the strategist who most accurately predicted 2018’s stock drop, has a view that differs from his own firm’s economists. They say a recession won’t happen any time soon.

But the strategist says if the Trump administration slaps 25 per cent tariffs on the remaining US$325 billion in Chinese imports to the U.S, net income among S&P 500 companies will fall by as much as 1.5 per cent — enough to depress corporate investment activity.

He cited something called a cycle indicator, which gauges the strength of the economy through a combination of metrics from the yield curve to consumer confidence to unemployment. The model tipped into a “downturn” phase last month, “which has always preceded an economic recession,” he wrote. In prior instances, 12 months after it’s happened stocks have trailed Treasuries by an average of six per cent.

JPMorgan Chase & Co’s head of cross asset fundamental strategy, John Normand, echoes Wilson in saying a trade war could push some of the biggest economic indicators into what he calls “recession-like” levels. Even after the worst week for equities this year, Normand says stocks can lose another 10 per cent.

“The left-tail risk is that we start to see recession-like levels on some of the big indicators that are affected by tariffs — these are things like global manufacturing, PMI indexes, capex and eventually corporate profits,” Normand said in an interview with Bloomberg TV Monday. “It doesn’t seem to me that equities are pricing in any kind of risk premium for the macro data looking a lot worse.”

Markets have come to terms with flat profit growth this year and wider stocks gyrations, but few have until recently voiced concern about the risk of an upcoming recession. Economic fundamentals have been solid, with unemployment falling to the lowest in half a century and GDP growth and manufacturing, though slowing, still showing a solid print.