Jan 25, 2022

Stocks Trading on Fumes Probably Aren’t Keeping the Fed Awake

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Don’t count on the Federal Reserve to ride to the stock market’s rescue so quickly this time.

Ultra-loose financial conditions, surging inflation and sky-high valuations all mean there’s little chance that Fed officials will step in to stop the bleeding, a growing chorus of Wall Street prognosticators say. After all, equities just doubled in three years, buoyed by the Fed’s monetary largess and its willingness to bail out investors whenever times got tough.

Now, losing a fraction of those gains in the name of controlling the cost of living will likely be seen as a small price to pay.

Take the Nasdaq 100. Even accounting for its recent travails, the index remains perched at five times the value of its constituents’ sales, a distance with few precedents other than during the dot-com bubble. At its height, the S&P 500’s price-earnings ratio topped 30. While it has since contracted to 24, the multiple is still 20% higher than its 10-year average.

“Any hopes of the Fed exercising its put option is just wishful thinking,” said Adam Phillips, managing director of portfolio strategy at EP Wealth Advisors. “With inflation at 7% and pressures expected to persist in the coming months, their hands are likely tied this time around.”

The Fed can take cover behind the strong signals emanating from areas of the market that are still rough proxies for economic growth. Stocks with shaky finances are performing decently, evidence that a slowing economy isn’t a problem the Fed needs to fix. In Wall Street patois, almost all the damage is being done on the ‘P’ side of the P/E ratio -- in prices, which are falling as earnings estimates remain firm.

None of this makes the last few weeks any less painful for investors. What started as an aggressive selloff in speculative corners has spread. With the S&P 500 down more than 7% since Dec. 15, stocks have now declined more between Fed meetings than any time since the pandemic crash in early 2020.

The risks of holding even moderately high valuation stocks right now played out in Tuesday night’s hammering in Microsoft Corp., whose post-earnings plunge sent an exchange-traded fund tracking the Nasdaq 100 reeiling. Despite sales and profit gains, a deceleration in revenue for cloud-computing services sent the shares down 5% after the close.

While the central bank is expected to signal a March rate hike and balance-sheet reduction later this year to help fight inflation, many traders are wondering whether Powell and his colleagues might soften their hawkish tone in light of the latest market turmoil. The last two times when stocks threw a tantrum like this, in March 2020 and December 2018, the Fed either turned outright dovish or put a halt to its tightening.

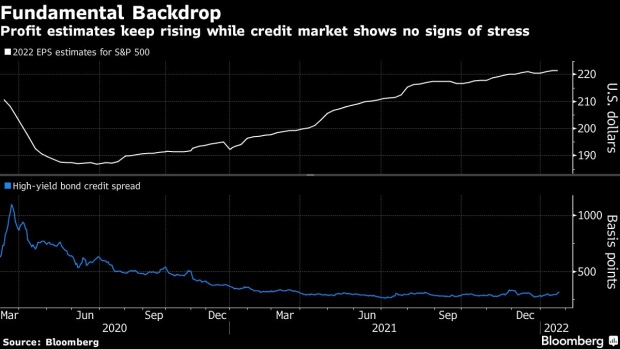

But the fundamental backdrop paints a different picture now. The economy is chugging along, with measures of financial conditions a long way from suggesting any hindrance to liquidity. While the S&P 500 is down 10% from its Jan. 3 record, premiums on junk-rated corporate bonds are subdued -- a sign of no credit stress.

Moreover, corporate America’s earnings power, the cornerstone of this bull market, remains strong. While profits from S&P 500 companies are estimated to expand 22% in the fourth quarter, half the rate seen in the previous period, that’s still more than twice as fast as the 10-year average, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence. Earnings sentiment kept improving as analysts has raised their 2022 profit estimates by roughly $1 to $221.4 a share since the start of the year.

All is giving the Fed some cover to stay in course of its tightening campaign, according to James Athey, investment director at Aberdeen Asset Management.

“The policy path of least regret is, for the first time in a generation, to deal with higher inflation and inflation expectations now and worry about the consequences for growth and financial market stability later,” said Athey. “This is a world that most investors have never experienced.”

Befitting a valuation scare, cheap-looking stocks are back in vogue and expensive growth stocks are out. A Goldman Sachs Group Inc. basket of companies with weak balance sheets has beaten its strong counterpart by more than 11 percentage points in January, on course for the best monthly outperformance since April 2009.

While earnings have underpinned the equity rally, some market watchers have blamed the Fed for fueling the runup in financial asset prices since the pandemic lows. To them, a selloff that drags valuations back down toward historical norms is not something the Fed should be concerned about, even if it brings short-term investor pain.

“Volatility is a feature of equity markets,” said Julien Lafargue, chief market strategist at Barclays Private Bank, by email. “The real anomaly is the unprecedented move we’ve seen since the pandemic trough.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.