May 23, 2022

Stressed-Out Supply Chain Managers Are Throwing in the Towel

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Supply-chain managers quit their jobs last year at the highest rate since at least 2016 due to a mix of burnout and a desire for fatter paychecks.

The high rate of turnover aligns with the escalation of supply-chain woes in 2021. The pandemic led to shuttered manufacturing plants, backed up ports and rapidly increasing transportation costs. Those headaches have largely fallen to supply-chain managers to sort out, making their jobs far tougher -- but also more lucrative.

“With increasing opportunities against the backdrop of the supply chain crisis, it comes as no surprise that supply-chain managers have increasingly sought out greener pastures,” said Kory Kantenga, a senior economist at LinkedIn.

LinkedIn, a division of Microsoft Corp., calculates turnover by analyzing member profiles to determine the number of people who left their jobs each month. The figure is compared with the average for 2016, which LinkedIn calls the “separation rate.” For supply-chain managers, the average separation rate increased by 28% from 2020 to 2021, according to data compiled for Bloomberg. That’s the highest since LinkedIn started tracking the data five years earlier.

Burnout is part of the equation, Kantenga said. New opportunities are also playing a role, in part because ongoing supply-chain disruptions are fueling demand for professionals who can deal with them.

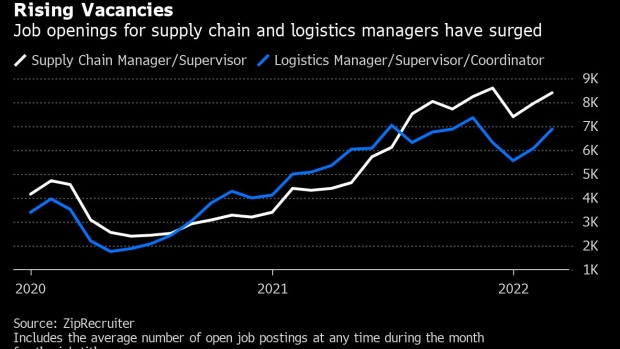

The number of openings for supply-chain managers on ZipRecruiter Inc.’s website more than doubled between January 2020 and March of this year, both because companies created more positions to deal with the crisis and because labor shortages gave workers more leverage to switch jobs, said Julia Pollak, the company’s chief economist.

Since Covid-19 emerged, shoppers around the world have faced empty shelves and shipping delays. Companies were forced to adapt to unpredictable demand, a race to secure scarce materials, and the stress of finding workers as their staff flocked to other jobs or fell ill. And then they had to find enough trucks to get their products out the door. The crisis raised the profile of supply-chain jobs, and the field became a popular major for business-school students.

The pandemic triggered a breakdown in “lean manufacturing,” the drive to lower costs that big companies had adopted in the decades prior. In practice, it meant that supply-chain managers had access to just enough staff, materials and trucks to fill average workloads. The model collapsed when Covid-19 brought in unexpected ebbs and flows in orders and hampered access to critical supplies, putting planners on a 24/7 fire-drill mode.

“So much became the exception versus the rule,” said Michael Martin, a supply-chain director in the Philadelphia suburbs who has held a variety of roles at companies such as Stanley Black & Decker Inc. and Essity AB over three decades. He took a new job at Blue Yonder during the pandemic. “I think that’s where a lot of the stress came from. We can’t solve problems as easily as we used to.”

Outdated Processes

The supply crunch hasn’t been limited to products consumers can hold in their hands. It has also affected tasks like data collection, which contribute to the bottlenecks experienced by businesses and shoppers.

Madhav Durbha, vice president of supply-chain strategy at Coupa Software Inc., said part of the problem is outdated processes. Manual and labor-intensive operations force employees to spend hours every week doing repetitive tasks that could be automated for greater efficiency and accuracy, allowing people to focus on more rewarding work.

For example, Durbha said 60% to 70% of an analytics employee’s time can be spent gathering data, while only 30% to 40% is dedicated to analyzing the figures and providing insights.

A survey released last year by recruitment firm DSJ Global showed that more than half of supply-chain and procurement professionals expected their paychecks to increase in the next 12 months. Higher pay was the No. 1 reason US workers were attracted to new jobs.

Supply-chain skills are in such high demand these days that job seekers can afford to be picky, said Emily Prendergast, an executive director at DSJ. She estimates that 65% to 70% supply-chain professionals are open to learning about new job opportunities within six months of getting their current position.

“Candidates are less willing to go to a firm that is outdated in systems or outdated in general processes,” Prendergast said. “They don’t want to be as stressed out as they have been over the last few years.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.