Sep 15, 2020

Suga Sets Sights on Structural Reforms for Debt-Ridden Japan

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Yoshihide Suga, the man set to become Japan’s new prime minister later today, has a reputation as a tough, task-based micro manager rather than a self-styled macroeconomic helmsman like Shinzo Abe.

Suga has vowed to stay true to Abenomics, but economists doubt there’s much more monetary pizazz to be squeezed out of the Bank of Japan or any more major spending splurges left in a public purse that’s already more reliant on debt than any other developed economy.

That leaves the third pillar of Abenomics, structural reform, as Suga’s best line of attack for reshaping economic policy. Suga sees himself as a reformer who wants to bring Japan’s bureaucracy into the digital age and tackle thorny issues such as regulatory reform and administrative inefficiency.

“I’m optimistic because under Abenomics -- and, of course, Suga was one of the major architects of it -- they did just about everything they could do on macro policy,” said Robert Feldman, senior adviser at Morgan Stanley MUFG. “Where Abenomics has been a little less aggressive has been on some of the structural reforms, this is an area where Suga is very eager to push forward.”

Read More: JAPAN REACT: Suga’s Strong Win Suggests Steady Policy Course

Suga has already called for more competition among mobile phone carriers to bring down fees and hinted at the need to weed out weaker regional banks. It remains to be seen whether he will continue to pinpoint industries at a micro level or broaden out to more wholesale change.

“I want to make solid progress on regulatory reform,” Suga said after becoming leader of the ruling party on Monday. “I want to take a proper look at things that are wrong, and move Japan forward by breaking down ministerial divides, vested interests, and a culture of just doing what’s been done before.”

Suga has a track record of keeping bureaucrats in line and consolidating their responsibilities, and even wrote a book about it. That suggests he may act quickly on administrative reform and setting up a digitalization agency.

He also worked in the deregulation-focused administration of Junichiro Koizumi that pushed the growth of jobs outside the cosy safeguards of Japan’s life-time employment.

A further breaking down of the wall dividing regular workers and contracted workers on pay and job security would likely impress economists, especially if it improves productivity. But Suga has remained quiet on the topic of labor market reform, casting some doubt on how radically he will try to shake things up.

Read More: New Japan Leader Seeks to End ‘Curse’ of Revolving-Door Premiers

He also has a hard act to follow. With big picture imagery, Abe generated optimistic expectations of change both at home and abroad when he swept to power promising to restore Japan’s economic power and prestige and wipe out deflation. Abe built confidence in Japan’s renewed direction again after years of short-lived premiers.

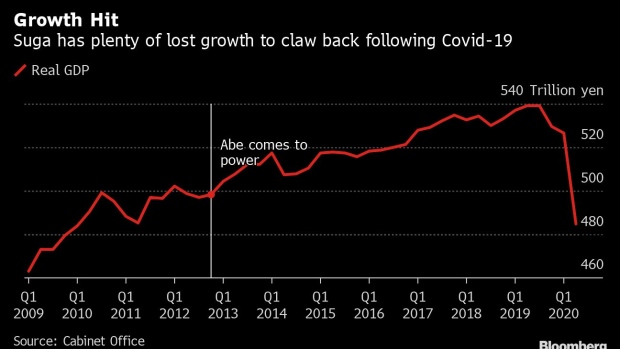

With an election due in little more than a year at the latest, the more domestic-orientated Suga will need to show he can hold on to voter and market trust to ensure he sticks around long enough to gain traction on reform. First, he’ll need to haul the economy out of a historic hole, after the battering of Covid-19, while keeping new infections under control.

He may even prefer to get an election out of the way early, before any risk of getting entangled in difficulties, to give his administration a clearer mandate and secure a longer-term premiership.

So far financial markets have found comfort in Suga as the continuity replacement. The Nikkei 225 has reversed losses since Abe’s shock resignation announcement on Aug. 28. The yen remains slightly softer against the dollar.

Suga has touted both a weaker yen and higher stocks as achievements of Abenomics, suggesting he will keep on the same path as long as these market yardsticks don’t change dramatically. But beyond that and a splash of reform talk, the new prime minister has kept his policy explanations to a minimum. He’s also yet to identify key economic advisers like Abe had in the reflationists Koichi Hamada and Etsuro Honda.

“We’re calling it Suganomics because Suga says he’ll maintain Abe’s economic policy, but it’s unclear to me whether Suga will really incorporate any particular policy mix as part of his strategy,” said Hideo Kumano, chief economist at Dai-Ichi Life Research Institute. “Maybe there’s not much economics in Suganomics at all. Talking about specific themes isn’t really a policy package.”

When Suga suggested a sales tax hike was inevitable last week, he quickly walked back those vote-losing remarks to align himself with Abe’s stance, an indication he doesn’t want to stray too far from the status quo. Economic growth must come before balancing the nation’s books, Suga has indicated. The burden of public debt to GDP is set to increase to 268% this year, according to Bloomberg Economics.

Markets will eventually price in any differences from Abe that emerge, according to Hiroshi Matsumoto, head of Japan investment at Pictet Asset Management.

“It’s a bit much to say Suga’s policy is too micro-oriented, but it does lack easy-to-understand talking points that will appeal to foreign investors,” Matsumoto said.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.