Aug 6, 2021

Sunak’s Rock-Bottom U.K. Borrowing Gets Warning Bell From BOE

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak’s quest to repair the U.K.’s pandemic-battered public finances just got an added impetus after the Bank of England began a countdown to the end of rock-bottom borrowing costs.

The central bank’s announcement on Thursday that officials will need to tighten monetary policy modestly in coming years points toward a slow-burning headache for the British finance minister.

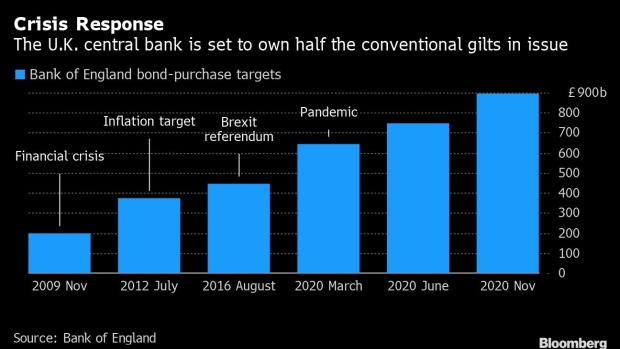

It means a gradual increase in interest rates and eventually unwinding holdings of nearly 900 billion pounds ($1.3 trillion) of government bonds bought under a program of quantitative easing to stimulate the economy.

That would put a stop to support Sunak has relied on to limit the cost of debt taken on to soften the blow of Covid-19. While investors don’t expect any BOE move until next year -- and even then only by small increments -- the scale of U.K. borrowing has left the public finances six times more sensitive to interest-rate changes than before the financial crisis, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility.

Given that backdrop, the Treasury may need to pay out more to service debt at the same time Sunak works to get the deficit under control. It’s an uncomfortable position for a Conservative chancellor who describes keeping the public finances under control as his “sacred duty” and counts debt as anathema to his political ideology.

“When times have been bad, QE has had the side effect of benefiting the government,” said Rory MacQueen, an economist at the London-based National Institute for Economic and Social Research. “Its only natural that when it unwinds, the government doesn’t have as much of the fiscal benefit from QE.”

Sunak is counting on a sustained economic rebound to replenish tax receipts and help repair finances in coming years. He has also repeatedly signaled that he’s watching interest payments due on the country’s ballooning debt.

“As interest rates and inflation change, that has an impact on our debt,” Sunak told GB News in June. “That’s one of the many risks it’s my job to worry about.”

The Treasury sidestepped the debate, noting that Sunak has already started preparing for a shift toward more normal borrowing costs.

“Changes in interest rates are among a number of risks to the public finances that we closely monitor, and that’s why at the budget in March the government set out the actions we are taking to ensure the public finances return to a sustainable footing,” a spokesperson for the Treasury said.

Britain’s deficit was almost 300 billion pounds in the year through March 2021, the equivalent of more than 14% of GDP. For the current fiscal year, the OBR’s last forecast envisioned that ratio holding above 10%, exceeding the worst outcome of the global financial crisis.

Those bills have been racked up by spending to protect jobs and businesses throughout successive national lockdowns. It included money for a furlough benefit protecting wages of those unable to work during lockdowns. It pushed the Treasury’s debt pile to 2.2 trillion pounds, the highest as a percentage of economic output since the 1960s.

Sunak has already asked departments to identify cost cuts, indicating a new dose of austerity ahead. That contrasts with the neighboring euro area, where governments are still spending more freely. The European Central Bank so far has been unhurried about determining the future of its own bond-buying.

While BOE Governor Andrew Bailey is aware of the pressure that any policy withdrawal would put on the public finances, he’s committed to a mandate of limiting inflation to 2% a year. On Thursday, he unveiled forecasts that showed annual price growth will reach 4% in the fourth quarter.

For now, the BOE has pledged to keep emergency policy in place, maintaining bond purchases for the rest of this year. The stimulus has meant historically low interest rates. It pushed government debt costs down to 0.9 % of GDP in 2020-21 from 3.8% four decades ago -- despite a debt-to-GDP ratio that more than doubled to about 100%.

The risks of a reversal could be costly. A 1 percentage point rise in interest rates now is “six times greater than it was just before the financial crisis, and almost twice what it was before the pandemic,” the OBR said in July.

With the U.S. Federal Reserve’s so-called taper tantrum of 2013 as a guide, the onus will be on the BOE to avoid any disorderly unwinding of QE. In the meantime, Sunak has already started preparing for the day when monetary stimulus is withdrawn.

“There is a tightening baked into the government’s fiscal forecast already,” said MacQueen. “To the extent that it comes forward slightly, that is in some ways offsetting some of the good news that will come about with the faster growth.”

Read More:

- BOE Warns Tightening to Be Needed as Inflation Seen Spiking

- U.K. Inflation Pushes Up Treasury Debt Payments to a Record

- U.K. Treasury Revenue From QE Would Reverse if Rates Rise: OBR

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.