Florida’s Home Insurance Industry May Be Worse Than Anyone Realizes

A rash of failures of A-rated insurers points to a hidden weakness in the market, researchers say.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

A rash of failures of A-rated insurers points to a hidden weakness in the market, researchers say.

US mortgage rates increased to the highest level in five months, pushing down home-purchase applications for the fifth time in the last six weeks.

A new book by University of Virginia professor Andrew W. Kahrl argues that the country has weaponized tax collection against its citizens for more than a century.

Chinese developer Country Garden Holdings Co., one of the biggest symbols of the nation’s broader property debt crisis, won approval to push back payments on three yuan bonds, people familiar with the matter said, staving off its first local default for now.

Iron ore climbed to the highest level in seven weeks as Fortescue Ltd., the fourth-biggest producer, said full-year shipments are likely to be at the lower end of guidance after disruptions hit supplies at mines in Western Australia.

Apr 8, 2021

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sweden’s housing market is now hotter than ever before, exposing weaknesses in the extreme policy mix pieced together by the world’s oldest central bank.

House prices in Scandinavia’s biggest economy jumped 17% in March from a year earlier to their highest ever, with a record number of homes sold in the first quarter, according to data published on Wednesday.

The price development has fed discomfort at the Riksbank which, like its peers, has had to commit to ultra-low interest rates to steer the economy through the pandemic. But the financial imbalances festering beneath the surface have prompted Sweden’s top central banker to paint a somewhat unnerving picture of what’s really going on.

“It’s like sitting on top of a volcano,” Governor Stefan Ingves said recently, referring to all the debt households have built up to pay for their homes. “I’ve been sitting on that volcano for many, many years. It hasn’t blown up, but it’s not heading in the right direction.”

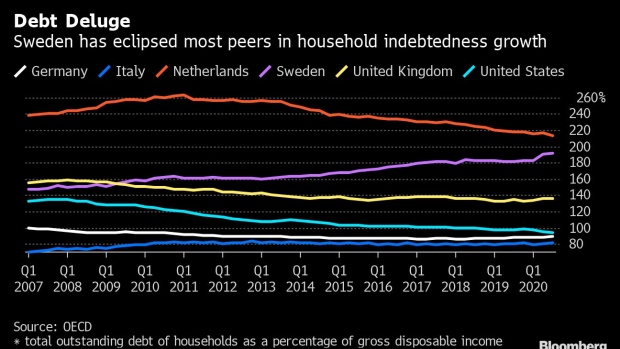

Consumer borrowing in Sweden reached 190% of gross disposable incomes at the end of last year. Ingves has monitored that growing pile of debt for years, watching for tremors that could signal danger ahead.

There’s little doubt that the Riksbank’s policies have contributed to the imbalance. The housing market development is in large part “driven by expectations of low interest rates for a long time to come,” according to Bjorn Wellhagen, the chief executive of Maklarsamfundet, a Swedish lobby group that focuses on the property market.

And it’s not just interest rates, which the Riksbank has held at zero throughout the pandemic. The bank’s purchases of the covered bonds that pay for home loans now make up the lion share of its 700 billion-krona ($81 billion) quantitative easing program.

Policy makers at the world’s oldest central bank don’t have an easy way out, since raising rates isn’t on the cards for at least three years, according to their own forecasts. Ingves also says it wouldn’t be a big problem if inflation exceeds the Riksbank’s 2% inflation target “for a number of years.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“The Riksbank is focused on the outlook for inflation and won’t be using its policy rate to cap the increase in house prices or credit growth. Stemming financial imbalances from the housing market will be up to Sweden’s financial watchdog (the Financial Supervisory Authority) or, preferably, the government which has the power to initiate structural reform.”

-- Johanna Jeansson, Bloomberg economist

Read More: Sweden Housing Market Hotter Then Ever as ‘Hysteria’ Fans Prices

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.