Mar 27, 2023

Swiss Politicians Pitch Credit Suisse Deal to a Skeptical Public

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Faced with growing public concern about the hastily-brokered merger of UBS Group AG and Credit Suisse Group AG a week ago, leading government figures involved in the deal turned to the local press to try to sell a skeptical public on the tie-up.

First it was Finance Minister Karin Keller-Sutter who on Saturday said the Swiss government was compelled to intervene to save Credit Suisse as the troubled bank wouldn’t have survived another day of trading amid a crisis of investor confidence. She was followed Sunday by the head of Switzerland’s banking regulator, who said the bank’s former management may face investigation.

“CS would not have survived Monday,” Finance Minister Keller-Sutter said in an interview with Zurich newspaper NZZ. “Without a solution, payment transactions with CS in Switzerland would have been significantly disrupted, possibly even collapsed.”

The impact of a disorderly bankruptcy may have been as much as double Swiss economic output, the minister said, citing expert estimates. More broadly, “we should have expected a global financial crisis” as “the crash of CS would have sent other banks into the abyss.”

The government-brokered purchase of Credit Suisse by UBS last weekend has been widely criticized for running roughshod over investors’ rights as well as possibly saddling Swiss taxpayers with a huge burden. But Keller-Sutter said the alternatives were worse.

The Swiss parliament will hold an extraordinary session after the Easter weekend to discuss questions surrounding the deal, according to the newspaper NZZ.

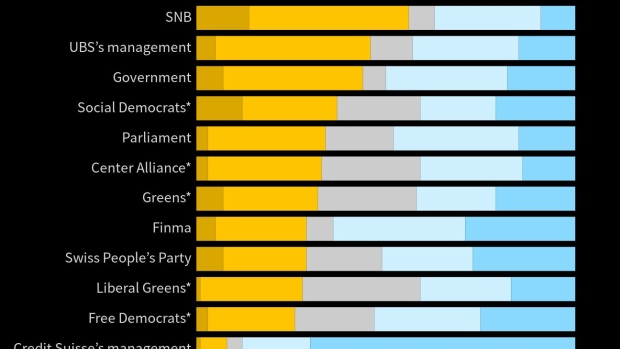

A poll by GFS on Friday showed that more than half of Swiss don’t approve of the deal. A second survey commissioned for Swiss Sunday tabloid SonntagsBlick showed that four in five Swiss want to see UBS spin off Credit Suisse’s domestic bank now because of concerns that a combined bank will stifle healthy competition.

“All other options were more risky for the state,” Keller-Sutter told NZZ. A temporary nationalization of Credit Suisse may have lasted far longer than the government wanted as “experience also shows that it can take years or even decades before the state can withdraw from ownership of a bank.”

But the Swiss public remains skeptical. The SonntagsBlick poll also showed that 61% of those surveyed said they either definitely or probably agreed with the idea of Switzerland nationalizing and later re-selling the bank.

An orderly wind down was also ruled out, because not only would the damage have been “considerable,” according to Keller-Sutter, but “Switzerland would have been the first country to wind down a globally systemically important bank. It was clearly not the moment for experiments.”

Keller-Sutter, a Free Democrat who’s faced some disquiet about the deal from some in her own right-of-center party, denied that the rescue amounted to a bailout, saying “there’s no money flowing from the federal government to the bank.” But she conceded the deposit guarantees are comparable to an insurance policy, making them “indirect state support.”

Finma Two-Step

On Sunday it was the turn of the president and chief executive of Finma, Switzerland’s banking regulator, to spread their message in separate interviews with Switzerland’s two leading German-language Sunday papers.

Echoing comments by Keller-Sutter, Finma President Marlene Amstad pushed back against the notion foreign regulators, particularly in the US, put pressure on Switzerland. “The Swiss authorities decided for themselves which solution was best,” she told NZZ am Sonntag.

Finma has come under scrutiny over whether it should’ve done more to prevent Credit Suisse’s collapse. Amstad rejected the suggestion that Finma didn’t intervene early or aggressively enough to tackle Credit Suisse’s problems, pointing to the six enforcement proceedings against the bank in recent years.

“We intervened earlier, and very intensively, where there were breaches of supervisory law. But especially when we act harshly, it usually doesn’t become public,” Amstad told NZZ am Sonntag.

Criticism of Finma also hinges on the fact that it lacks the authority to fine banks or individuals to dissuade bad behavior. Amstad said she welcomes a debate about giving Finma the tools to deter excessive risk-taking or rogue bankers.

“When it comes to the responsibility of individual decision-makers, however, it is evident that there are gaps that need to be closed,” Amstad said.

Even with a limited arsenal, Amstad told NZZ am Sonntag that Finma is weighing up whether to open proceedings against Credit Suisse.

“CS had a cultural problem that translated into a lack of accountability,” Amstad told NZZ am Sonntag. “Often it was not clear who was responsible for what. This favored a negligent handling of risks.”

“We’re not a law enforcement agency, but we’re exploring options,” she said.

--With assistance from Zoe Schneeweiss.

(Updates with parliament special session in sixth paragraph)

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.