Mar 10, 2023

Systemic-Risk Fears Put an End to 2023 Stock Market Miracle

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- It’s one thing when crypto gets flattened by a fired-up Federal Reserve, or moonshot online stocks fall back to earth as rates soar. But when central bank policy starts biting into banks, investors know they have bigger problems on their hands.

Fear of systemic risk ripped across markets this week, when investors who thought they’d survived the worst of Jerome Powell’s war against inflation suffered their biggest stretch of losses in five months. Bank shares, assumed to be redoubts of safety in a rising-rate world, led the plunge, posting their worst week since the Covid crash.

While the jury is out on whether the failure of SVB Financial Group bespeaks pervasive risk to the financial system, hints that it did were enough to strike fear into investors who last month were sitting on gains approaching 10% for 2023. The advance dwindled to less than 1% at the end of Friday and bulls are left with a twisted hope that things may be so bad that Powell’s Fed won’t dare raise rates much more from here.

“This situation is going to lead the Fed to move more incrementally,” said Alec Young, chief investment strategist at MAPsignals. “Everyone was worried in the back of their minds about something breaking — people think, ‘well this is the thing that’s breaking.’”

This week’s events dented a main plank of the bull case for stocks — essentially that nobody was being hurt much by rising rates. Consumers and large firms, the story went, insulated themselves from Jerome Powell’s zeal by locking in loans back when yields were nothing. But banks have emerged as an exception to that hope as higher rates saddle lenders with paper losses on bond portfolios and lure depositors away. If too many defect, the paper losses can quickly turn into realized ones.

For investors broadly the question becomes whether anxiety over the banking system is enough to fuel another major down-leg in a bear market that began 14 months ago. Skittish traders are aware that the financial crisis crash of 2008 didn’t see its worst stretch until about a year into the selloff, when the Lehman Brothers failure sent the S&P 500 down 30% starting in September of that year.

Few are predicting that kind of carnage this time, though nothing puts bulls on higher alert than the suggestion of systemic risk. Brent Donnelly of Spectra Markets believes this week’s fall from 4,100 on the S&P 500 could be the start of a rapid selloff targeting 3,650 to 3,700 over the next week — a drop of more than 5% from the Friday close of 3,861.59.

“It’s ready, shoot, aim right now. You can’t sit there as a depositor and ponder things — you just get out,” Donnelly said of investors in the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF. “If you’re long KRE, you just get out and then think about what to do.”

Silicon Valley Bank became the biggest US bank to fail in more than a decade, toppled by a cash exodus from the tech startups it had catered to for 40 years. The collapse came days after crypto-friendly Silvergate Capital Corp. announced it would liquidate and wind down operations.

The corresponding plunge in bank stocks and contagion fears dragged the S&P 500 4.5% lower this week, its worst performance since September. The index’s year-to-date gain is virtually gone, after hopes that the Fed might be nearing the end of its tightening cycle fueled a robust rally at the start of 2023.

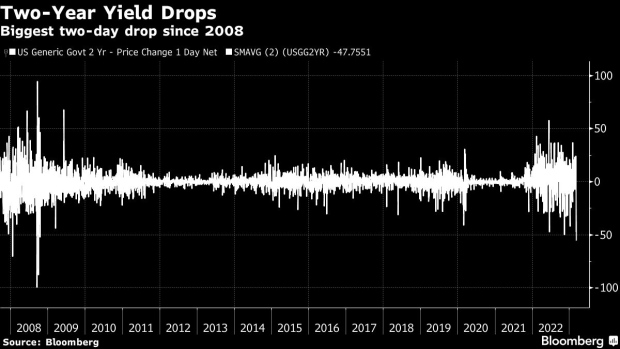

Now, traders are once again pricing in the possibility that the central bank might soon back off hikes and actually lower rates by year end. That lead to the two-year Treasury yield’s biggest two-day drop since 2008, after breaking through 5% for the first time since 2007 earlier in the week.

But that recalibration is of little comfort to equity bulls this time around.

“Especially in an inflationary environment, they keep moving until something breaks,” Michael Collins, PGIM Fixed Income senior portfolio manager, said Friday. “I would argue the risk of something breaking is now tilting to be a little bit higher than the risk of runaway inflation.”

Even if no systemic risk materializes, SVB’s travails were a reminder that banks may struggle to generate earnings even in a rising rate environment. That’s a potential headache for everyone, given the group is forecast by analysts to have the second-highest profit growth among S&P 500 industries this year.

While higher rates are often thought to buttress interest income, the issue is complicated in 2023 by a steeply inverted yield curve that depresses yields on longer-dated assets versus short-term liabilities. Retaining deposits is hard when money market rates are as much as 50% higher than interest paid on savings accounts. And if deposits flee, banks may be forced to book what had only been paper losses on mortgage bond and Treasury holdings they are forced to sell.

SVB ended up being the posterchild of that problem, given it served the breed of venture-capital backed firms and startups struggling with cash crunches as the Fed tightens the screws.

“This is just another example of things breaking in an economy that has gotten very used to low interest rates for a decade and a half,” said Ellen Hazen, chief market strategist and portfolio manager at F.L. Putnam Investment Management. “When those rates start rising, both nominal and real, which is what has been happening for the last year, things are going to break, because there were entire business models built on free money.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.