Sep 14, 2022

T. Rowe Slams Goal-Linked ESG Bonds Doing Little Good

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- On paper, it looks like a perfect deal for green-minded investors. They buy the bonds of companies that agree to slash their environmental footprints -- and pocket higher yields if the businesses are penalized for falling short of the goals.

To Matt Lawton, T. Rowe Price Group Inc.’s portfolio manager for global impact credit strategy, however, it often looks like little more than a ruse.

Lawton said the so-called sustainability-linked bonds, or SLBs, exemplify some of the most “egregious behavior” by Wall Street banks and companies eager to exploit the surging demand for investments that advance the social good. Why? Because the targets are sometimes so easily achieved -- or so weakly enforceable -- that they render the whole point behind the investment strategy effectively meaningless.

“It’s becoming increasingly difficult to find credible SLBs,” he said in an interview. “The banks are pitching these structures really hard so I definitely approach them with a healthy degree of skepticism.”

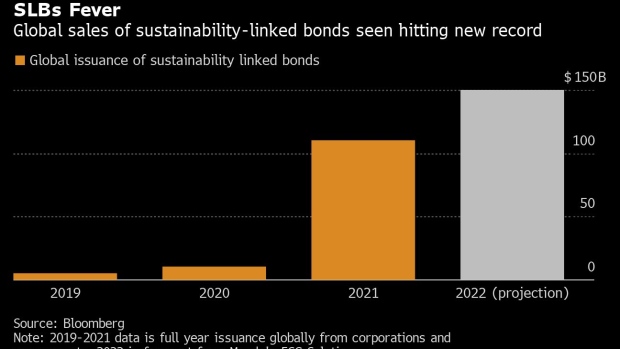

Companies globally have been rushing to issue SLBs to get cheaper borrowing costs by tapping into the tide of cash that’s flowing into environmental, social and good-governance investment funds. Sales of the bonds reached a record $110 billion in 2021 and Moody’s ESG Solutions is expecting $150 billion by the end of this year.

T. Rowe, which oversees some $1.4 trillion of investments, is the latest bond-buying titan to raise doubts about how well the bonds advance the stated goals. Last year Nuveen, another big investor, said it saw little impact from the securities and has continued to focus its efforts on structures that clearly identify their use of proceeds and impact outcomes.

“The banks are trying to structure them in such a way that is attractive for the issuer and right now investors are falling over themselves to buy these bonds,” Lawton said. “I don’t know how much discernment is actually happening on the investor side.”

Related: Borrowers Embrace Bonds That Ensure Against Betrayal of ESG Vows

SLBs can be used by a wide pool of borrowers, including companies that are financing day-to-day operations instead of large industrial projects.

Lawton pointed to Tesco Plc’s inaugural sustainability-linked bond, which priced in January 2021. The UK-based grocery-store chain tied the 750 million-euro, 8.5-year bond to a pledge to cut 60% of its direct and indirect greenhouse gas emissions through 2025-26, with 2015-16 as the baseline. But the company had already achieved a 50% cut in those emissions by the time the deal was sold.

Tesco said in an emailed response that its SLB framework was independently assessed by Sustainalytics, who found its sustainability performance targets to be “impactful and ambitious.”

Lawton said the enforcement mechanisms behind other deals mean the goals matter little in practice. For example, Level 3 Communications Inc.’s $900 million SLB deal, which also priced in January 2021, can be repurchased from investors in January 2024, before any penalties for not meeting the sustainability targets even kick in. Level 3 was acquired in 2017 for $34 billion by communications service provider Lumen Technologies Inc. (formerly known as CenturyLink).

Lumen’s global issues director Mark Molzen said in an emailed response that a call feature is common in these sort of instruments and a matter of financial prudence for any issuer to manage their interest rate exposure and balance sheet flexibility over time. “The fact that we were able to successfully issue sustainability notes without having to forego these sort of basic features shows the natural demand for these sorts of instruments,” Molzen added.

Chemicals firm Nobian Finance BV also sold an SLB that’s callable before the targeted goals, meaning the company could evade any potential penalty simply by exercising the option to repurchase the securities.

In its emailed response, Nobian said that sustainability is one of its business priorities and the fact that it pays back debt at specific dates has “no impact on our commitment to reach our sustainability targets and our efforts to report transparently about our progress on an annual basis.”

The International Capital Market Association, which sets voluntary principles in the ethical debt market, in June updated guidelines for issuing SLBs to bolster transparency in the market. Issuers should ensure the structure of any SLB requires their performance against at least one sustainability performance target -- or SPT -- be evaluated prior to the bond becoming callable at the issuer’s option at a pre-determined price, according to an accompanying Q&A that addresses the materiality assessment of SLB targets.

The new guidelines encourage issuers to set the target observation date or payment of penalty date before the call date. Meanwhile, there are now more flexible version of SLBs that allow issuers to adjust targets under certain conditions, without getting bondholders’ permission or incurring a penalty.

“Where there is an early first call date, and evaluation against an SPT is impracticable, investors will likely expect the call price to reflect an assumption that the SPT hasn’t been met,” according to the Q&A.

Read more: Creditors Lose Some Rights as ESG Bond Market Allows Legal Tweak

The securities have been a lucrative line of business for Wall Street banks, which have been raking in billions of dollars in underwriting fees for ESG-related bond sales and hiring to gain an edge in the fast-growing industry. But that growth also has threatened to dilute the power of such investing as banks aggressively market securities to the influx of cash pouring into ESG funds.

Lawton said the high demand from investors means that banks can easily water down the targets set for companies that hire them to underwrite the bond officers.

“The banker could theoretically say to their issuer, ‘Here are the bare minimum targets you need,’ and the market will accept it,” Lawton said.

(Adds details on flexible version of sustainability-linked bonds in 16th paragraph.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.