Apr 30, 2021

Tesla can’t just keep preaching to the converted

BNN Bloomberg

McCreath: Tesla has a role to play in tech underperformance

Tesla Inc.’s quarterly earnings calls have a ritualistic feel; more of a pageant for devotees than a forum for scrutiny. Yet this week’s event was helpful, if only because it showcased the difficulties of pleasing the fans while trying to expand the crowd.

Nine days before Tesla reported results, two people died in a fiery crash near Houston involving a Tesla Model S. Initial reports that no one was in the driver’s seat fueled speculation that Tesla’s Autopilot driver-assistance software was involved. CEO Elon Musk pushed back, but on the call mostly deferred to Lars Moravy, Tesla’s VP of vehicle engineering. He said various indications — road condition, distance driven, seat belts being unbuckled — implied Autopilot’s functions either couldn’t have been engaged or couldn’t have led to a high-speed crash. And the “deformed” steering wheel made it “a likelihood” someone was driving at impact.

Yet the mystery remains, not least because the local fire marshal’s report confirms there was nobody behind the wheel in the. Moravy’s explanation suggests adaptive cruise control was used at some point and the car came to “a complete stop” when the driver’s seatbelt was unbuckled, raising further questions about what seems like a bizarre sequence of events. For example, did the driver use (or misuse) the cruise control feature, stop, hit the pedal, crash and slam into the wheel so hard it deformed, and then somehow move seats as the car burned?

Rather than disappear down the Reddit-hole of blaming either Autopilot or the driver, this may have been a case of a driver abusing a driver-assistance feature that has a long, YouTube’d history of being abused. Tesla makes clear that, despite the nomenclature of Autopilot and its upgrade, Full Self Driving Capability, the cars aren’t autonomous and drivers should keep their hands on the wheel.

And yet, go to the relevant Tesla site and you’ll see a short video that begins like this:

Any driver-assistance system is open to abuse. I’m guessing, though, that marketing it with phrases like “the car is driving itself” might raise the risk of that. Liza Dixon, who researches human-machine interaction, has dubbed this emerging problem of a mismatch between vehicle automation capabilities and branding “autonowashing.” A study published last September by the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety found this mismatch had real effects on drivers’ risk tolerance.

Tesla’s position is confusing. On the same call where Moravy addressed criticism in part by highlighting Autopilot’s limitations, Musk boasted “we appear to be able to do things with full self-driving that others cannot.” Musk has talked of fleets of money-spinning robotaxis (forthcoming), yet the latest 10-Q filing dryly states that future iterations of Tesla’s type of self-driving technology might not “perform as expected in the timeframe we anticipate, or at all.”

Even if regulators appear less concerned (for now), investors should be. Lawyers write the filings, but Tesla’s vehicles are ultimately judged in the court of public opinion. And if ambitious growth targets are to be realized, then that court must expand enormously.

Tesla’s latest financials underscore the importance of this issue. Attention on earnings day focused on Bitcoin’s boost to earnings, but Tesla’s subsequent SEC filing revealed a change in accounting treatment of convertibles helped too.

A market cap of US$650 billion demands so much more. Assume vehicle deliveries expand more than 20x by 2030, each one sold for US$50,000 at a net margin of 10 per cent. Even then, the implied multiple on these imagined (and immaculate) earnings way out in 2030 is still more than 11x, higher than where most automakers trade on next year’s forecasts.

And as electric vehicles move toward being just “vehicles,” and competition heats up, software and automation will become more important selling points and revenue streams. Getting the technology, and public perception of it, right is crucial.

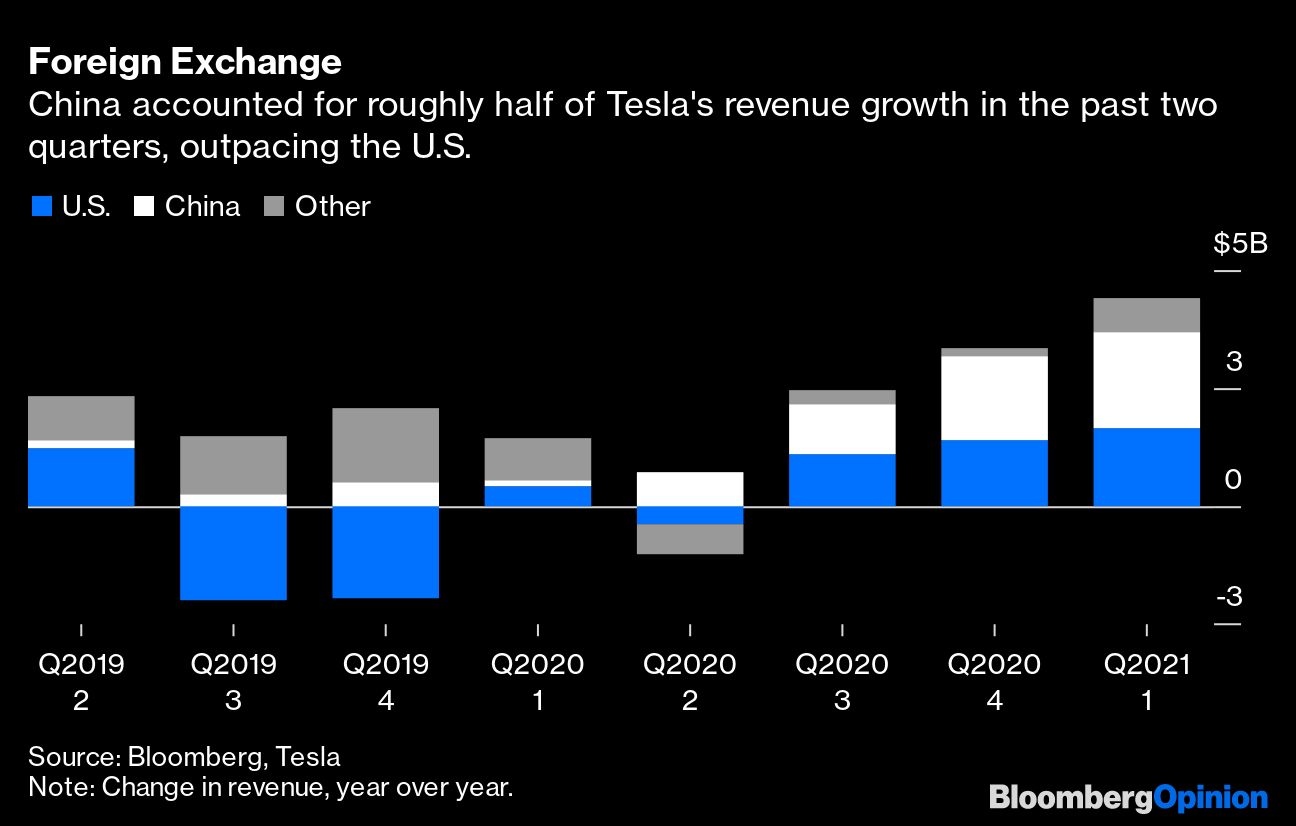

Tesla’s recent black eye in China is relevant here. There’s been a public outcry over how it handles customer complaints, including scathing articles in Communist Party-linked press. Tesla apologized quickly, in contrast to its approach with U.S. regulators. As well it might: China has overtaken the U.S. in terms of Tesla’s revenue growth.

As my colleague Anjani Trivedi writes, Tesla’s vehicles are popular in China, both with consumers and suppliers. Provided Tesla addresses its critics there with enough tact and urgency, it should be fine.

Rather, the Chinese backlash, like disquiet around Tesla’s branding of vehicle autonomy, gets at the tension between where Tesla is today and where its valuation demands it go. Tesla is priced for simultaneously changing the world and conquering it — profitably. That means selling unfamiliar products and services to a lot more than first-adopters, even as rivals crowd in and regulators catch up. Unlike the earnings call crew, that crowd will be less forgiving.