Dec 9, 2022

Thatcher Playbook Calls for Massive Pay Rise for Public Workers

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Margaret Thatcher would be awarding Britain’s public sector workers a hefty pay rise to end rolling strikes and avert a winter crisis, according to a senior economist who studied her time as prime minister.

Willem Buiter, a founding member of the Bank of England’s rate-setting committee and former global chief economist for Citigroup Inc., said “there clearly is a lesson for today’s Tory government” from Thatcher’s early actions when she came to power in 1979.

Thatcher is remembered as the Conservative Party prime minister who took on the unions in the 1980s and won. But, Buiter pointed out, her success came only after handing public sector workers a 25% pay rise in 1979 to avert a second successive “winter of discontent.”

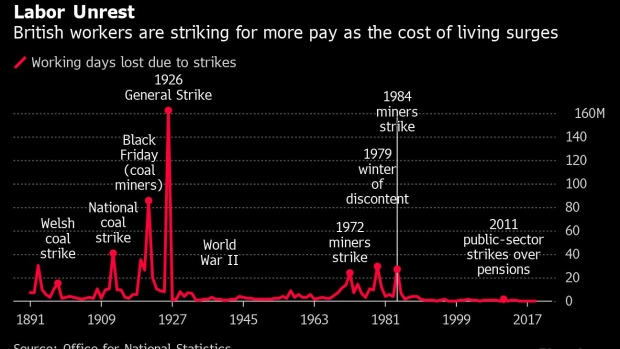

Much like today, the UK was gripped by strikes between November 1978 and early 1979, which caused inconvenience and made the country appear ungovernable. The chaos ultimately led to Thatcher’s Conservatives defeating the Labour government in May 1979.

Rishi Sunak, who took office as prime minister in October, is grappling with rolling strikes from health, post and rail workers as well as planned action by teachers and border force staff.

He has pledged to keep pay rises under control to ward off inflation, which currently is at a four-decade high of 11.1%. He’s concerned about a wage-price spiral and has promised “tough new laws” to take on the unions.

Sunak has refused to offer more than 5% on average for public sector workers, a real-terms pay cut and less than the 6.8% increase those in the private sector have enjoyed so far this year. The clampdown follows several years of pay restraint that have led to a recruitment crisis in key public services, most notably the National Health Service.

In July, Simon Clarke, who was chief secretary to the Treasury when Sunak was Chancellor of the Exchequer, quoted Thatcher as saying there was “no alternative” to pay restraint.

In 1979, Thatcher came to power promising to tackle high inflation. But she initially chose to stick to the system that meant the public sector got a 25% rise in 1979-80 — more than the 19% for those in the private sector.

Not until summer 1980 did she did abolish the inflation-linked incomes policy that lay behind the era’s wage-price spiral, according to Buiter’s analysis. Speaking to Bloomberg, he warned that persisting today with pay offers of “well below the rate of inflation” risked “public sector class war.”

“Pay and working conditions were already poor enough in the health and social care sectors to cause acute under-staffing problems even before Covid struck,” Buiter said. “Add a nurses strike to that, and you have the makings of a health and social care disaster.”

“If necessary, fund the public sector pay increases with higher taxes on the rich. For once, social justice and economic efficiency point in the same direction.”

Increasing the UK’s 5 million public sector workers’ wages by 10% would cost an additional £12.5 billion this year, the Treasury estimates.

One set of public sector workers will get double digit rises. Those who have retired will see a 10% increase in their income as public service employment pensions rise annually in line with inflation. This coming year that will cost the taxpayer about £5 billion.

Buiter’s comments follow similar calls from Charles Goodhart, another former BOE rate-setter, and Toscafund Chief Economist Savvas Savouri. They warn that deterioration in public services will hurt the economy and only delay an inevitable public sector pay explosion.

The Treasury has said it is following the recommendations of the independent Pay Review Bodies, who will also determine next year’s increase that will come into effect in the summer. Sunak has also insisted that some pay settlements are better for certain public sector workers than their private sector counterparts.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.