US GDP Report Set to Highlight Immigration-Driven Economic Boom

Initial data on US gross domestic product for the first quarter of 2024 is set to confirm an ongoing economic boom amid a tailwind from surging immigration.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Initial data on US gross domestic product for the first quarter of 2024 is set to confirm an ongoing economic boom amid a tailwind from surging immigration.

Oracle Corp. is moving its headquarters out of the city. Tesla Inc. is pulling back after a rapid expansion. Almost a quarter of commercial office space is vacant, and nowhere in the country have residential real estate prices fallen further from their pandemic peak.

Mortgage rates in the US increased for a fourth straight week.

It’s independents, a growing voting bloc, who drive election victories in the swing state, where the GOP is rushing to defuse abortion as an issue.

Pending sales of existing US homes in March reached their highest levels in a year in spite of persistently high borrowing costs and a low supply.

Jan 18, 2022

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

There’s more at stake than an interest-rate hike at next month’s Bank of England meeting, giving traders extra reason to correctly call the decision from the increasingly unpredictable central bank.

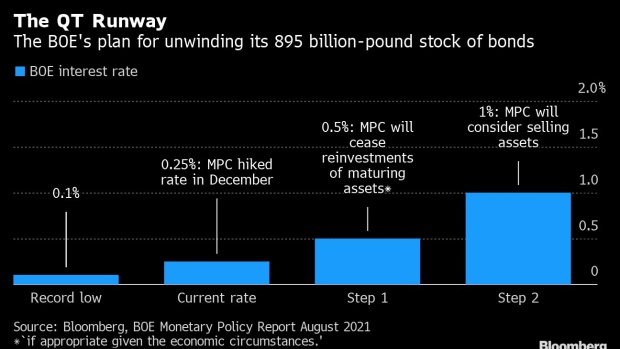

If it pulls the trigger and raises interest rates to 0.5%, that would be the first back-to-back hikes since 2004. It also opens the door for the BOE to start reducing its record balance sheet by stopping the reinvestment of expired bonds. That would affect 28 billion pounds ($38 billion) of gilts maturing in March.

But while rate increases are a known quantity, so-called quantitative tightening is uncharted territory.

For more than a decade, bond holdings have only moved in one direction, meaning there’s no playbook for what comes next, when the BOE is no longer the biggest buyer in the market.

That has specific implications for the government, creating the risk of a rapid increase in borrowing costs that dents Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak’s plans to restore order to the public finances.

Ten-year gilt yields are up more than 40 basis points since the BOE raised rates in December, threatening to break through the 1.20% resistance level.

“It’s about much more than just a hike. It’s a double whammy,” said David Parkinson, Sterling Rates Product Manager at RBC Capital Markets. “It does really up the ante for the February meeting.”

With U.K. inflation heading for a 30-year high of 6%, markets are pricing in a 90% chance of a hike on Feb. 3. However, the BOE has wrong footed investors before, most recently late last year.

Halting reinvestments isn’t automatic once rates hit 0.5%, but the BOE’s guidance makes it a live question for February.

The QT conundrum is one policy makers around the world are contending with, including the Federal Reserve, which may start its own balance-sheet unwinding later this year.

In the U.K., the end of QE breaks a link between BOE stimulus and government spending that saw the former accused of monetary financing -- the direct funding of governments by central banks.

Since the pandemic began, the BOE’s buying has mopped up much of Sunak’s unprecedented borrowing to fund crisis spending, and kept a lid on yields.

Crucially, the end of reinvestments would leave the bond market contending with a flood of new gilt issuance without the backstop of an ever-ready buyer.

RBC expects net issuance after QE to be the highest in about a decade for the next fiscal year, at 82 billion pounds versus 35 billion pounds in 2021/22. With that in mind, markets are bracing for deeper concessions into bond auctions and larger price swings.

The influx of supply without a central bank buyer could also accelerate the steepening of the yield curve that’s been squeezed in part by a dearth of longer-dated debt.

Once the BOE rate hits 1%, which is priced in for August, the BOE has said it will consider actively selling its bond holdings.

“You could argue that it’s an environment which no market participant has faced with the level of volatility that’s potentially in play,” said Edward Hutchings, senior portfolio manager at Aviva Investors. “You also have a whole host of employees at various institutions who haven’t experienced anything other than quantitative easing.”

However, the BOE has wiggle room to avoid triggering the March run off. It’s guidance on stopping reinvestments at 0.5% includes the clause “if appropriate given the economic circumstances.”

“The decision to hike or not in February will be probably distinct” from reinvestments, said James Smith, an economist at ING in London. “They could hike and then say, ‘Alright, we’re going to commence the balance sheet unwind in April.’ They don’t necessarily have to go hand in hand.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.