Mar 14, 2017

'The bubble popped': How dozens of Canadian investors beat Ackman to the punch on Valeant

Bill Ackman is bailing on Valeant Pharmaceuticals (VRX.TO), but the American activist was beaten to the punch by more than 50 major Canadian investors.

The Canada Pension Plan Investment Board, which owned roughly 780,000 shares as recently as March 2015 on behalf of millions of working and retired Canadians, reduced its position to effectively nothing one year later. What happened in the interim – the fraud scandal surrounding the Valeant’s mail-order pharmacy Philidor and increasing controversy surrounding its strategy of dramatically increasing drug prices – scared off scores of other major investors as the stock that once dominated the Toronto Stock Exchange was decimated.

“We owned it for the industry consolidation business model,” Toronto-based Portfolio Manager Stephen Caldwell, whose firm Cidel Asset Management owned a Valeant stake similar in size to that of CPPIB at the start of 2015, told BNN via email. “[But] when the Philidor revelations came out it was obvious that that strategy wasn’t an option going forward and the insurers would tighten up on coverage of their drugs so we sold it.”

Cidel sold its Valeant position in October of 2015 and two polls conducted by BNN of the top money managers on Bay Street over the following month found they considered the stock “uninvestable” by a more than two-to-one margin. In fact, data from Thomson Reuters shows more than half of Valeant’s Canadian investors had sold off virtually all -- or the entirety -- of their respective stakes in the company from late 2015 through February 2017, with only four Canadian shareholders continuing to hold a million or more Valeant shares.

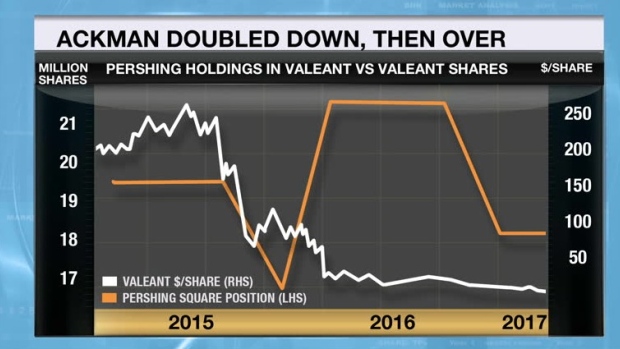

And yet, Ackman doubled down.

His firm, Pershing Square Capital Management, picked up an additional four million Valeant shares from late 2015 through March 2016, despite Ackman apologizing to Pershing shareholders for not doing the exact opposite.

“When the [Valeant] stock price rose to the mid-[US]$200s per share, we did not sell as we believed it was probable the company would likely complete additional transactions that would meaningfully increase intrinsic value,” Ackman wrote in a letter dated January 26th 2016.

“In retrospect, this was a very costly mistake,” Ackman wrote.

More than a year later, Ackman has come to realize how costly the mistake had truly been. Pershing sold its remaining stock in recent weeks for an average of US$11 per share, having originally paid an average of US$196 per share in early 2015.

“[Valeant] played the momentum game incredibly well,” Lyle Stein, managing director of Vestcap Investment Management, told BNN on Tuesday, noting his firm never owned Valeant shares. “They used debt on the basis that the equity value is growing in the marketplace. Debt ratios didn’t look too bad until, unfortunately, the bubble popped.”

Before that happened, the company under former CEO Michael Pearson managed to rack up an extraordinary amount of debt. Unlike a traditional pharmaceutical company that invests in research and development to market new drugs and bring in new sources of revenue, Pearson orchestrated more than 50 mostly debt-financed acquisitions during his seven years as CEO.

Pearson’s buying spree saddled the company with more than US$30 billion in debt and as the stock plunged, Valeant was no longer able to continue its growth-by-acquisition strategy. Shortly after Joseph Papa replaced Pearson as CEO in late 2016, the company pledged to pay back roughly US$5 billion worth of its total debt by mid-2018.

While that would still leave the company with a debt load totaling more than five times its current sub-$5-billion market value, Rodman & Renshaw senior healthcare Analyst Ram Selvaraju told BNN on Tuesday there is no “immediate-term risk” of bankruptcy. Selvaraju also does not think Ackman’s withdrawal indicates there might be “some major shoe to drop that other investors don’t know about.”

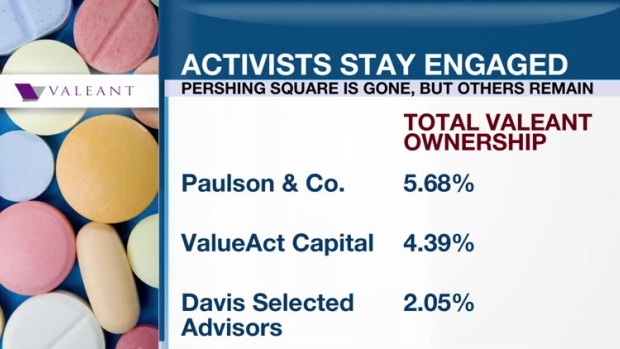

Other major U.S. activist investors such as Paulson & Co, ValueAct Capital Management and Davis Selected Advisers remain among the five largest Valeant shareholders; between them controlling more than 12 per cent of the company. However, with the embattled drugmaker struggling to shift to a more traditional business model, remaining shareholders are left to wonder what alternatives the company is still capable of pursuing.

“The growth by acquisition strategy always ends badly,” said Vestcap’s Stein. “The problem with debt is you can’t get out.”