Apr 28, 2021

The car makes a COVID comeback, and that means burning more oil

, Bloomberg News

It’s starting to feel as commonplace as handwashing: To protect against COVID, people across the globe are skipping trains and buses. Instead, they’re part of the great car comeback that’s sending vehicle sales soaring and fueling a demand surge for oil and metals.

Julie Murataj is a reluctant part of the shift. Two of her three kids are now getting dropped off at school instead of taking public transit. Then she drives her Volvo SUV to work, where she helps London schoolchildren cross the road by halting traffic with a bright, red and yellow stop sign that Brits call a “lollipop.” It’s a front-row seat to the world’s changing travel habits.

“There are many, many more cars,” Murataj said. “I’m seeing the roads busier now than they used to be pre-COVID.”

After being stuck in their homes for so long, people are itching to get out again. It’s a boon to newly reopening economies, with consumers ready to start spending more at gas stations, convenience stores, restaurants, hotels and attractions. Daimler AG, BMW AG and Toyota Motor Corp. all started the year with sales at records, and things are so hot that used car prices in the U.S. are soaring to all-time highs.

The jump in vehicle sales is a strong sign that this is more than just a passing fad. Like the ubiquitous face mask, the car renaissance could be the latest example of how COVID-19 makes a lasting impact on our lives. The change could usher in an era of heavier traffic jams and longer commutes. All the extra driving will send gasoline consumption soaring, but with that also comes a rise in pollution. The increase in gasoline use that the International Energy Agency projects for this year alone would add as much as 1.5 billion pounds of carbon emissions per day.

Traffic in Hong Kong is already twice as congested as in 2019. The streets of Tel-Aviv, Moscow and Bucharest are all busier now than they were before the pandemic, according to TomTom NV. In the U.S., driving miles on highways are starting to top 2019 levels, and in the U.K., fuel sales are already at similar levels to last summer’s peak.

“People have a lot of cash in their pockets, and as lockdowns ease places will open up and allow those kind of leisure trips that may have been blocked,” said Richard Bronze, co-founder of London-based consultant Energy Aspects.

Gasoline is the big winner.

Profits from making the fuel are near seasonal five-year highs and are expected to stay strong as the Northern Hemisphere heads into summer driving season. U.S. refiner Valero Energy Corp. says gasoline sales are nearly at pre-pandemic levels, and the biggest bulls are predicting demand could hit a record. The U.S. Energy Information Administration expects summer fuel prices to be the highest since 2018 this year.

The picture extends across the globe. BP Plc said this week that oil demand in China is back above pre-pandemic levels. In Europe, gauges of road congestion compiled by Bloomberg and covering 15 nations just posted their strongest reading in 10 weeks as the region emerges from another wave of the virus.

In Japan, an explosion for drivers-license applications signals a lasting shift to car travel. Applications processed in Shizuoka Prefecture, south of Tokyo, rose 8.7 per cent in 2020, according to prefectural police. It’s the first significant rise in the past decade. The bulk of applications came from people in their 20s, a marked change from pre-COVID times when younger generations were increasingly choosing to forgo car ownership.

“We’re pretty bullish on gasoline going forward,” Gary Simmons, chief commercial officer at Valero, said on a call last week.

Other commodity markets are also getting a boost. Copper, aluminum, palladium and platinum, used in car parts, are seeing strong demand. And consumption is robust for corn and sugar, used to make ethanol, as well as soybean oil, used in biodiesel. With more crops going into fuels, it’s likely to exacerbate the food inflation that’s already crimping consumer wallets.

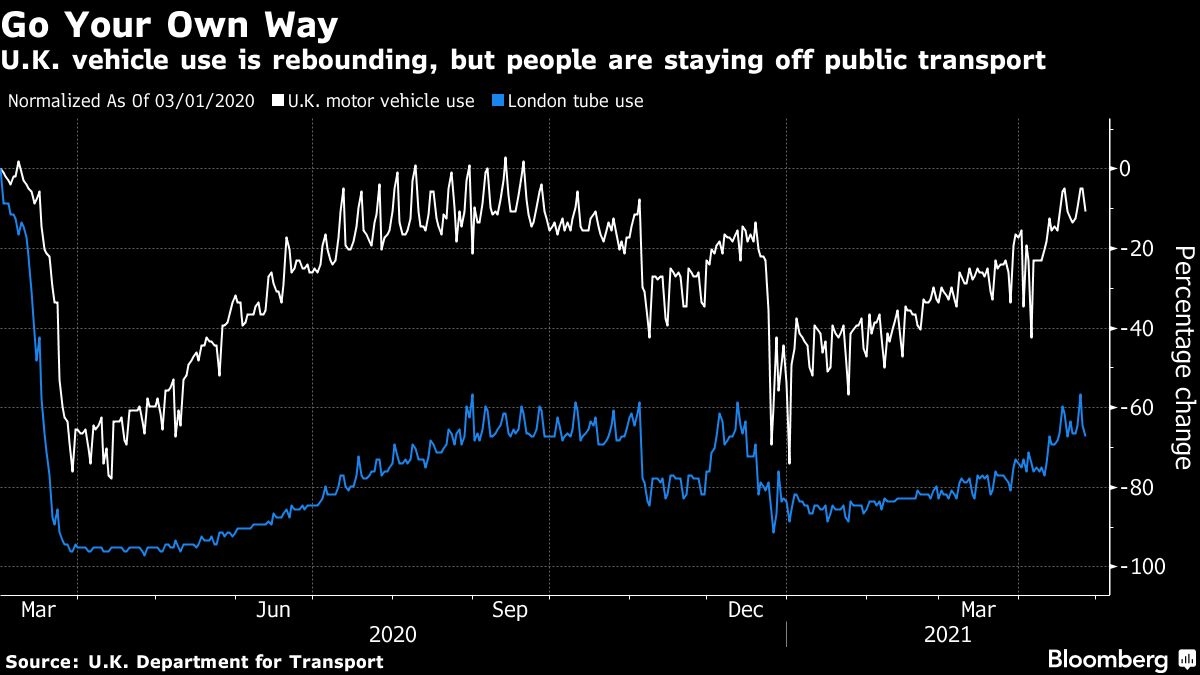

Meanwhile, largely empty rail and metro carriages are ferrying just a handful of commuters in some of the western world’s largest cities. That’s putting a hole in the finances of mass transit systems like New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority, German state railway Deutsche Bahn and Transport for London, which operates the U.K. capital’s tube network.

The move away from mass transit helps explain why the world’s carbon emissions are coming back fast after last year’s historic drop.

Earlier this month on London’s Marylebone Road, which runs alongside one of the U.K. capital’s royal parks, nitrogen-dioxide levels hit the highest since before the country’s first coronavirus lockdown, according to Imperial College London. The pollutant is mainly produced by diesel traffic, according to Simon Birkett, founder of not-for-profit Clean Air in London.

London crossing guard Murataj is an asthmatic and can easily tell you about the change.

“Through the first lockdown, when literally nobody was going anywhere, my breathing improved so much,” she said. “It was like being in the country or by the sea. I didn’t need to use my inhaler.”

But now?

“It’s probably worse now than it was” before COVID, Murataj said.

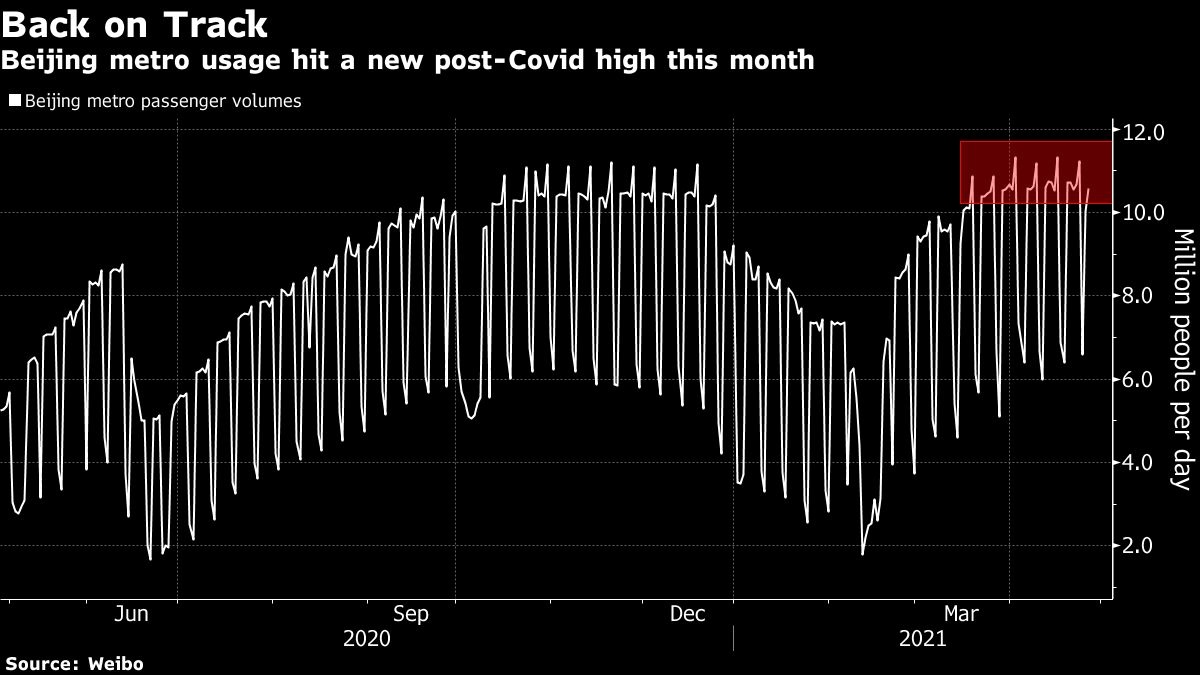

China, further along than most of the world in its coronavirus rebound, offers some insight on how long the car mania will last.

When lockdowns first started to ease last year, commuters in Beijing abandoned the city’s crowded metro and began commuting by car. But with the world’s second-largest economy staving off subsequent COVID waves and traffic jams in Beijing almost as bad as 2019, metro passenger volumes hit a post-COVID high this month.

The big difference, though, is the world outside of China has struggled to keep cases in check, especially in light of new virus variants. Parts of Europe have been in and out of lockdowns to deal with infection spikes, the Philippines’ case count breached 1 million this week and Japan has declared a new state of emergency in Tokyo, Osaka and two other prefectures.

Of course, the biggest virus threat is now in India, which is battling the world’s largest surge in COVID-19.

Vinkesh Gulati owns dealerships of both new and used cars in Faridabad, outside of Delhi. Demand is so strong that some of his customers are on a six-month waiting list, depending on what model they’re interested in. The congested city streets mean that in years past many buyers opted to travel by two-wheeled scooter or motorcycle. But now, the open-aired vehicles are being shunned.

Customers “often tell me that they are buying cars to move around to overcome the boredom and frustration of staying at home all the time,” said Gulati, who’s also president of the Federation of Automobile Dealers Associations, which represents 90 per cent of dealers in the country.

“They can leave on a weekend morning, drive for 200 miles and come back in the evening. It’s a good family outing.”

That desire for travel is expected to surge in the coming months, when the Northern Hemisphere basks in summer weather. Office workers have a store of vacation days to enjoy and kids will be out of school, so many families will be loading up their cars and hitting the road.

Some people are already making the move.

Saad Rahim is the Geneva-based chief economist at Trafigura Group, one of the world’s top independent commodity trading houses. He’s driving at least twice as much as he was before the pandemic began, mostly on family road trips around Switzerland.

Being in a car is like being in “your own bubble,” he said. “People are taking advantage of that.”