Fancy Apartment Rentals for Paris Olympics See Poor Demand and Price Cuts

Locals who’d hoped to turn a big profit by renting out their posh apartments are now slashing prices by 30%-60%.

Latest Videos

The information you requested is not available at this time, please check back again soon.

Locals who’d hoped to turn a big profit by renting out their posh apartments are now slashing prices by 30%-60%.

The kingdom must overcome a conservative image and concern about human rights. Visit the desert oasis town of AlUla to understand the challenge.

Jury selection was completed Friday for Donald Trump’s first criminal trial, setting the stage for opening arguments Monday in a New York case accusing the former president of falsifying business records to conceal a sex scandal before the 2016 election.

Higher-than-expected interest rates amid persistent inflation are perceived as the biggest threat to financial stability among market participants and observers, according to the Federal Reserve.

Fifth Third Bancorp jumped the most in four months, leading bank stocks higher, with Chief Executive Officer Tim Spence predicting that income from lending has bottomed out.

Apr 16, 2019

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For investors in U.K. Plc still nursing their wounds from last year’s implosion of Carillion Plc, the most frightening words in the English language also begin with C: Construction contractor.

On Tuesday, Galliford Try Plc, which partnered with Carillion on a troubled Scottish road project, said it would cut the size of its infrastructure business. With that strategic review underway, it’s become clear that problems on various long-term contracts, including a road bridge spanning the Firth of Forth, will result in a hit of as much 40 million pounds ($52 million). That’s more than a quarter of estimated full-year profit.

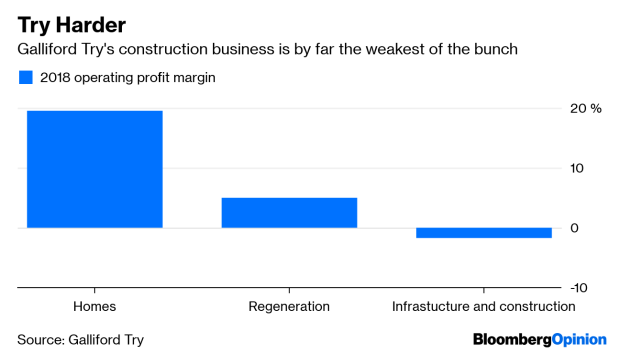

In theory, shrinking the infrastructure business is a welcome first step by new chief executive Graham Prothero (who served previously as finance director). The group has a very profitable house-building business that’s benefited from rising prices and government subsidies for home buyers. It also has a fast-growing urban regeneration unit.

In contrast, public contractor projects are suffering from low margins and have a nasty habit of ending in cost overruns, as the Carillion debacle and troubles at peers like Kier Group Plc and Interserve Plc have shown. Analysts ascribe little or no value to Galliford Try’s construction business, even though it’s the group’s largest by revenue.

Yet news of the downsizing still sent the shares tumbling 19 percent on Tuesday, wiping out some 150 million pounds of equity value – more than three times the estimated profit impact.

What gives? While the company insists that most of its construction contracts are performing well, shareholders probably fear more bad news. They’ve certainly had their fair share recently. Galliford Try has already booked 30 million pounds of exceptional items so far this financial year, while the Carillion insolvency resulted in a 45 million pound hit to profit in 2018. In the year before, Galliford’s exceptional charges were almost double that.

This must be frustrating for long-term shareholders, many of whom forked out for a discounted 158 million pounds rights issue shortly after Carillion’s collapse. It won’t make them any happier to know that management bonuses are linked to earnings that strip out the exceptional items.

In fairness, the latest problems relate partly to projects taken on years ago. Executives couldn’t have foreseen Carillion’s insolvency and aren’t to blame for high winds, which have held up one project. The group has stressed lately that it will be far more selective in bidding for contracts, which is reassuring.

The shares now languish more than 60 percent below a 2015 peak and trade on less than five times estimated earnings, although net debt remains pretty modest. Until shareholders can get comfortable that there are no other skeletons in the construction cupboard, escaping the shadow of Carillion will be a struggle.

To contact the author of this story: Chris Bryant at cbryant32@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.