Oct 5, 2022

The Debt Deal That Shows How Ugly Things Are Getting for Lenders

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Markets) -- The lawyers filing into Kirkland & Ellis’s New York headquarters on April 7 had cleared their calendars for days. They knew they were attempting one of the most ambitious and complex financial maneuvers in corporate finance history, and it would require marathon negotiations.

Coffee, sandwiches, and a seemingly endless supply of fresh popcorn—a Kirkland staple—were on hand. The law firm was hosting the talks on behalf of its client, Envision Healthcare Corp., a hospital staffing company owned by KKR & Co.

Envision was in deep trouble. Higher labor costs, a drop in hospital visits unrelated to Covid-19 during the pandemic, and new legislation to protect patients from surprise medical bills had dealt a blow to its prospects. That was raising concern about Envision’s ability to support the roughly $7 billion debt load KKR had layered onto the company to finance its 2018 buyout. KKR was underwater on what had been its largest-ever equity investment.

On the other side of the table that day were representatives from Angelo Gordon & Co. and Centerbridge Partners, fund managers known for making bold bets on distressed debt. They hadn’t previously lent to Envision. Now they were offering more than $1 billion of fresh financing—with a catch. To get the cash, Envision would have to strip the company’s most promising division—a business called Amsurg—from existing creditors and pledge it as collateral for the new loan.

Amsurg (short for “ambulatory surgery”) was capitalizing on a huge shift in health care: Doctors are increasingly able to perform same-day procedures outside of traditional hospital settings. The unit, which accounted for about 15% of Envision’s revenue, had lower costs and less exposure to uninsured patients than other parts of the company and had bounced back quickly after the pandemic, according to a report by Moody’s Investors Service.

The collateral move relied on an aggressive interpretation of Envision’s debt documents that was sure to anger existing creditors, including Pacific Investment Management Co., the company’s largest lender. The two hedge funds were confident they could pull it off.

Ryan Mollett, who joined Angelo Gordon from Blackstone Inc.’s credit unit in 2019 and ran the distressed debt business, had a penchant for creative financings. He was the mastermind behind a controversial deal for Hovnanian Enterprises Inc. that upended the market for credit-default swaps in 2018. The Centerbridge team, led by Shanshan Cao and Gavin Baiera, knew Envision particularly well. The firm’s private equity arm had itself looked at the company as a potential acquisition before KKR’s purchase in 2018.

To tell this story, Bloomberg Markets talked to 10 people with direct knowledge of the negotiations, who spoke on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to comment publicly.

Other struggling companies owned by private equity funds—including J. Crew, Neiman Marcus, and Petsmart—had used similar asset moves in recent years to restructure their debt and stave off bankruptcy. But the Envision deal marked the first time that an investment giant like KKR, viewed as more conservative than its peers, was willing to take the gloves off in this way.

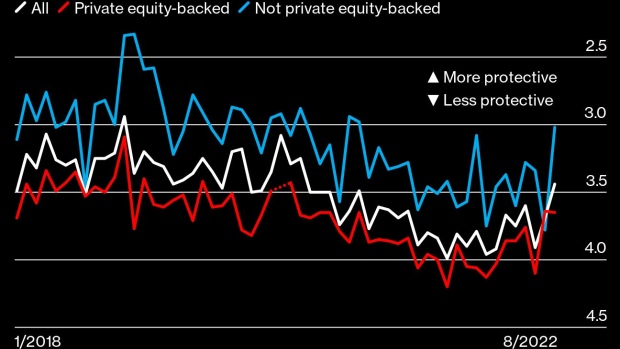

Such maneuvers had been a decade in the making. Easy money after the global financial crisis made debt investors hungry to buy loans and bonds that provided higher yields. Funds began to agree to weaker protections in their creditor agreements. Loan and bond documents riddled with loopholes and imprecise language gave borrowers more flexibility in times of stress.

The documents didn’t explicitly allow future creditors to grab collateral. But they left just enough ambiguity, sometimes called “trap doors,” for lawyers with a bit of ingenuity and a lot of motivation to move assets to new entities and give dying companies some fresh capital. Because of these often-overlooked provisions, some creditors were surprised to discover they’d been left with almost worthless loans and bonds after struggling companies restructured.

“Loose documents have become the norm rather than the exception,” says Damian Schaible, co-head of restructuring at Davis Polk & Wardwell. “If we go into a real recession, we are going to see more and more borrowers and sponsors seeking to exploit document loopholes to create leverage against and among their creditors.”

Credit rating companies and analysts have warned that these looser protections could leave debt investors struggling to recover their money when borrowers file for bankruptcy or pursue out-of-court restructurings. In 2020, as the pandemic pushed scores of heavily indebted companies into default in spite of an unprecedented intervention by the Federal Reserve, recovery rates on corporate debt lagged those of previous default cycles, according to Moody’s.

Envision, which also explored a consensual debt exchange that would have raised less funding, ultimately opted for what is considered one of the most controversial and coercive out-of-court restructurings to date. The deal with Angelo Gordon and Centerbridge would prove to be just the beginning of a series of maneuvers that eventually allowed the company to restructure the vast majority of its debt but forced creditors to turn against one another.

The strategy rested on two pillars. The first was a drop-down transaction, in which a company’s most valuable assets are moved away from existing creditors and used as collateral for new debt. The second was a series of debt repurchases and exchanges that gave certain creditors priority over others and pushed anyone who declined to participate to the end of the line for repayment.

Kirkland was particularly adept at finding trap doors in bond and loan language for its clients. For the past decade, the firm had touted its ability to design agreements that give an edge to the borrower, as well as its skill in handling the restructurings and bankruptcies that may follow. Crafting and exploiting loopholes in debt documents had become an art form for Kirkland’s attorneys.

Simpson Thacher & Bartlett, which counts KKR as a top client, had also honed this skill. The two firms have produced the most borrower-friendly loan agreements since at least 2018, according to data from Covenant Review, a research firm owned by Fitch Group that analyzes credit agreements and bond indentures for investors.

Simpson Thacher had negotiated the Envision documents on KKR’s behalf. But as Envision’s outlook darkened, it turned to a team at Kirkland led by two veterans known for their prowess in navigating through bankruptcy and restructuring.

Josh Sussberg is possibly the most ubiquitous bankruptcy attorney in the US, appearing often in courts from New York to Texas. In 2017 he represented Toys ‘R’ Us in an Eastern District of Virginia court when it filed the biggest retail bankruptcy in over a decade.

An expert in corporate governance, Sussberg ensured that the flow of information to, and decision-making by, Envision’s board of directors didn’t open it or the company to litigation. Like any company owned by private equity, Envision needed to prioritize its long-term survival over the returns of its owner, in this case KKR. Complex restructurings often raise questions about whether those priorities are being respected. Sussberg had to ensure that important decisions throughout the process were made by the board’s independent directors—those without an official affiliation with KKR—to indicate that KKR wasn’t pulling the strings.

Meanwhile, David Nemecek, a finance partner at Kirkland, examined the documents for months to determine how best to structure an asset move that would preclude legal objections. On this he worked closely with Envision’s investment bank, PJT Partners.

Nemecek and his team hit on the idea of using an intercompany loan from Amsurg to Envision to transfer the proceeds of the new debt. The main reason for the deal was to inject new cash into Envision, but structuring the payment as a loan served an additional purpose: It increased Amsurg’s value in a way that supported discounting the original lenders’ term loan and exchanging it for second-lien debt, an important part of cutting Envision’s total liabilities.

Envision first designated Amsurg as a so-called unrestricted subsidiary, effectively moving it out of reach of existing creditors without violating provisions in the credit agreement that prohibited moving or transferring the asset. The Amsurg assets would then be used as collateral to borrow $1.3 billion from Angelo Gordon and Centerbridge, who’d effectively be stepping ahead of everyone else in the repayment waterfall. Envision could then use the cash raised from the hedge funds to boost liquidity and to repurchase some of its existing debt at steep discounts.

Some of Envision’s existing lenders organized to stop the plan. They considered suing the company with the help of the law firm of Marc Kasowitz, a top Wall Street litigator who’s also served as one of Donald Trump’s personal attorneys. But before too long, the group dissolved. After a series of tense phone calls, at times punctuated by expletives, some of the lenders recognized that Envision and Kirkland were unmoved by threats of litigation.

A group of lenders led by Pimco and including HPS Investment Partners, King Street Capital Management, and Sculptor Capital Management, took stock of their options. They decided to participate in the new financing alongside Angelo Gordon and Centerbridge, providing a large chunk of the new loan. They also exchanged their existing holdings for new debt with a second-priority claim on the same Amsurg assets at a steep discount of 66¢ on the dollar. The rest of Envision’s creditors had to fight for the leftovers, without Amsurg. They were able to exchange their debt for longer-dated debt backed by the remaining Envision assets in a transaction that split lenders into four classes. Ultimately, only $153 million of the original loan was left outstanding, as owners of 96% of the debt had exchanged their holdings and waived their rights to litigate the transaction in the future.

There was a bitter irony in the way most of the company’s creditors ended up competing for crumbs. Four years earlier, when Credit Suisse Group AG sold the debt that financed KKR’s purchase of Envision, demand was so high that a salesperson teased investors with a picture of cake crumbs on a plate. The message then: Hurry up and grab it before it’s all gone.

For some, the Envision tale is just a prelude in what could become a series of aggressive out-of-court restructurings. “The sponsors still have the leverage,” says Davis Polk’s Schaible. “Creditors recognize at this point that everyone is on their own.”

Ronalds-Hannon covers distressed debt for Bloomberg News in Atlanta, and Scigliuzzo is a senior credit market reporter in Los Angeles.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.