Nov 9, 2018

The Dollar Is a Haven in Sea of Uncertainty

, Bloomberg News

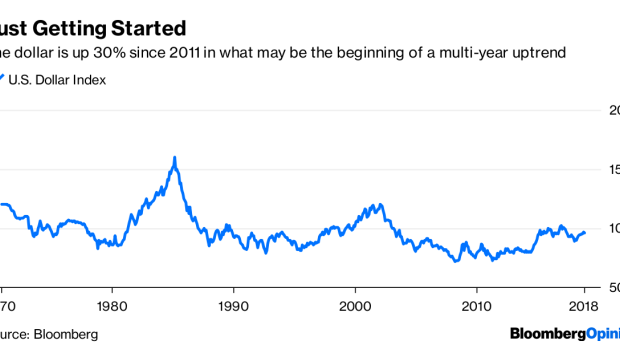

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The dollar has gained about 30 percent against a basket of other major currencies since the start of August 2011, which just happens to be the month that S&P stripped the U.S. of its AAA credit rating. Putting aside the debate over whether credit ratings actually matter for the world’s primary reserve currency, the question at the moment is whether the greenback can keep strengthening. The answer is an unequivocal yes.

In fact, the dollar is in for a number of years of substantial increases. Consider that the currency’s recent rally as measured by the U.S. Dollar Index came after a 52 percent slide that started in March 1985. Put another way, it’s still 37 percent below that peak 33 years ago. More fundamentally, the dollar is one of the few havens in a sea of global uncertainty. That’s true even if the U.S. institutes the troubles.

The world was quite content when the U.S. was absorbing the globe’s excess goods through American imports, with limited reciprocity, especially from China. Then the Trump administration disrupted that tranquility by demanding a more favorable trade deal with Mexico and Canada as well as putting pressure on Europe to ease the entry of American products. But that was just a warm up before President Donald Trump instituted tariffs on Chinese goods, kicking off a trade war between the world’s two biggest economies.

We’re only beginning to see the resulting supply chain disruptions, the scrambling by American firms to offset tariff hikes with cost-cutting, price increases and shifts to other suppliers. Meanwhile, the Chinese are depreciating the yuan to offset the tariffs, moving production to non-affected countries such as Vietnam and easing monetary policy. All of this turmoil benefits the dollar, and the vast differences between the U.S. and Chinese policies suggest that this trade war will continue for some time.

Trump has the upper hand since the U.S., the primary buyer in a world of ample supply, has the advantage over the seller, China. Besides, where else could China sell $534 billion in products it sent to the U.S. last year? The pragmatic Chinese will no doubt import more U.S. products, demand less technology transfers as the price American firms pay for operating in China and steal fewer U.S. trade secrets.

That will reduce the chronic U.S. trade and current-account deficits. The $500 billion current-account deficit is the number of dollars the U.S. pumps into foreign hands. Some 87 percent of all global transactions involve the U.S. dollar. So a lower deficit will result in a global dollar shortage and a higher value for the greenback will no doubt result.

Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve is shrinking its balance sheet assets at an accelerating pace. One byproduct of the Fed’s decision to cut its holdings of Treasuries and government-related securities is that it absorbs dollars from domestic and foreign investors, further reducing the supply of greenbacks.

The U.S. economy is growing faster than almost every other developed country, with cumulative real GDP growth of 19.5 percent from 2007 through the second quarter, compared with 9.1 percent in the euro zone and 6.5 percent in Japan. China surpassed Japan in 2010 to become the world’s second-largest economy, but last year U.S. GDP was still 50 percent larger than China’s. America’s deep and broad financial markets also support the dollar. The combined market capitalization of the New York Stock Exchange and Nasdaq was $32.1 trillion last year, versus. $11 trillion in the euro zone, $8.7 trillion in China and $6.2 trillion in Japan. Treasuries, a primary store for foreign money, totaled $15.3 trillion in 2017, double heavily-indebted Japan’s $7.6 trillion and $6.1 trillion in China.

My Bloomberg Opinion column of April 25 stated that the dollar’s pre-eminent status among global currencies should remain intact because it continues to meet my six long-term criteria for the dominant international currency. Now I’m adding a seventh reason: Trump’s willingness to exercise America’s economic and financial power on the world stage.

With a strengthening greenback, investors should avoid or short emerging markets. Their huge dollar-denominated debts cost increasingly more in local currency to service. Also, their dollar-traded commodity imports cost more. Of 45 internationally-traded commodities, 42 are dollar-denominated.

U.S. multinationals are also hurt as their exports cost more abroad and their foreign earnings translate into fewer dollars. Furthermore, competing imports are cheaper for Americans, to the detriment of domestic production. Not surprising, changes in the dollar and the S&P 500 are inversely correlated.

To contact the author of this story: Gary Shilling at agshilling@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

A. Gary Shilling is president of A. Gary Shilling & Co., a New Jersey consultancy, a Registered Investment Advisor and author of “The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation.” Some portfolios he manages invest in currencies and commodities.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.