May 24, 2020

The Dow Jones is getting crushed in the recovery trade

, Bloomberg News

China-U.S. trade will weigh on markets moving forward: David Prince

Next week marks a milestone for the Dow Jones Industrial Average: its 124th birthday. Not that anyone watching markets needs a reminder it’s getting old.

Wrinkles show in the gaping divide between the venerable gauge and its younger brethren. Like many grandparents, it’s struggling to keep up with tech. Plunges in Boeing Co. — its biggest member at the start of February — were very costly, and some wonder if the benchmark represents the 21st century economy at all, especially in the coronavirus age.

“The Dow has been on its way out for years,” said John Ham, associate adviser at New England Investment and Retirement Group. “Obviously it’s going to stick around just because so many people are familiar with it. But as far as relevancy goes, it’s your grandfather’s index.”

Rarely have differences among indexes been more stark than they are now, in a market where the outbreak has made heroes of New Economy firms. Deprived of their benefits, the Dow remains down 14 per cent in 2020 and was off 35 per cent at its worst point. Meanwhile, the Nasdaq 100 has gained more than seven per cent this year, and the S&P 500 is nine per cent away from a positive return.

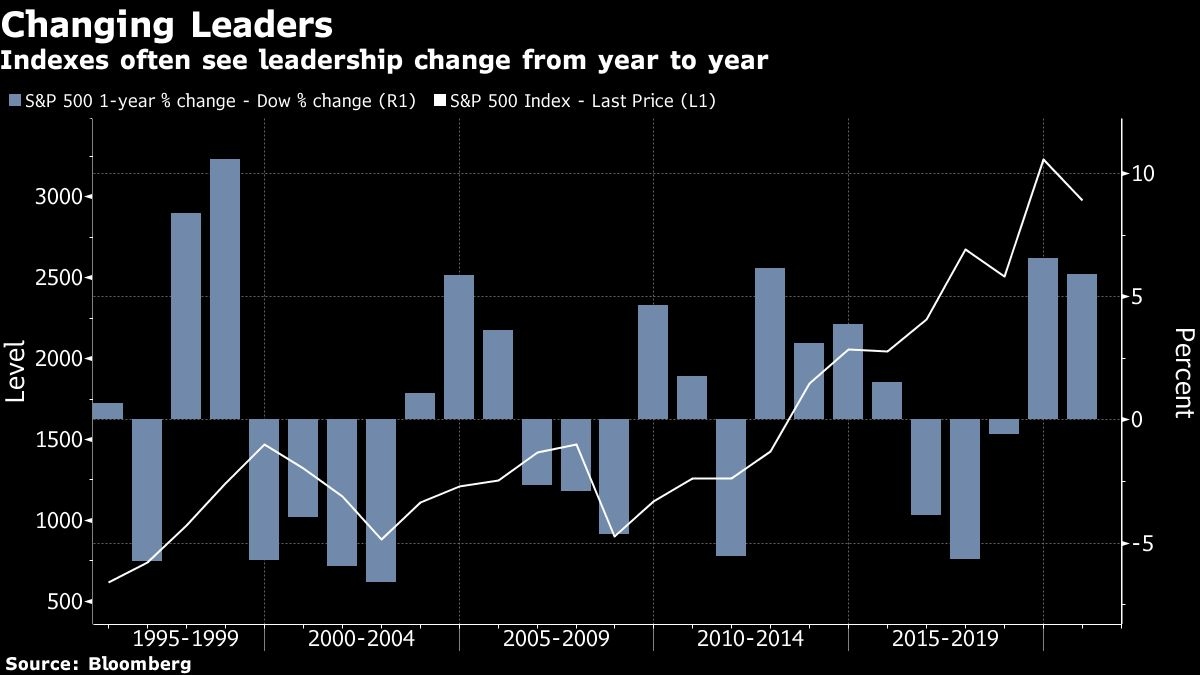

Of course, the Dow has been consigned to history before, and survived. While it might be showing its age now, brief divergences among broad indexes are extremely common, and over long enough intervals they tend to even out.

“Yes it is old,” said Howard Silverblatt, senior index analyst at S&P Dow Jones Indices. “If you constructed something today, you would probably do it differently. But it’s worked for 124 years. Even currently. And it is a much smaller portfolio yet it does track over time to the broader S&P 500.”

Judging an index by whether it rises more than another misconstrues the purpose of stock benchmarks, which is to measure the progress of a market. The S&P 500’s edge over the Dow in 2020 doesn’t make it a better or more useful tool. It does, however, shine a light on what in the economy is calling the shots during the lockdown -- online and automated companies like Amazon.com Inc. and Netflix Inc.

Divergences among the gauges also matter to the masses of investors who invest in funds that track them. Roughly US$11.2 trillion is indexed or benchmarked to the S&P 500, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices, and US$4.6 trillion in passively managed assets are tied to it. About US$31.5 billion is benchmarked to the Dow, with US$28.2 billion of passively managed funds linked.

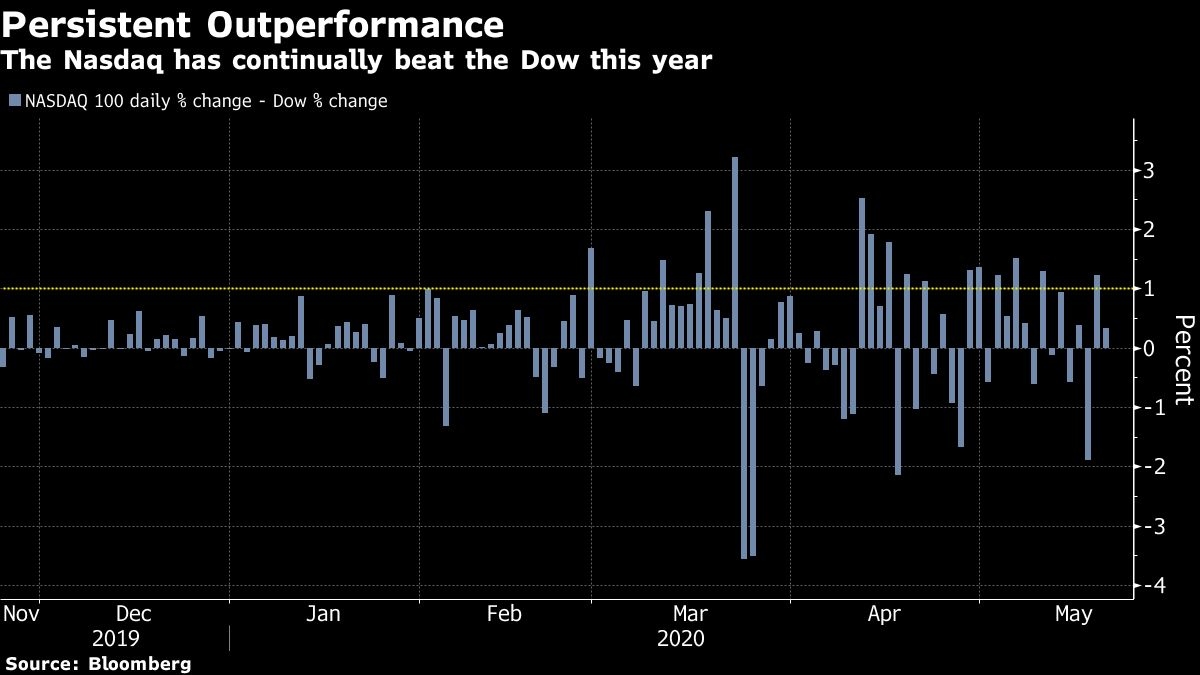

Thanks to tech’s dominance, those divisions are getting especially pronounced. Less than halfway through the year, the Nasdaq has already outperformed the Dow by a full percentage point on 17 different days. That’s more than in any full year since 2009, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

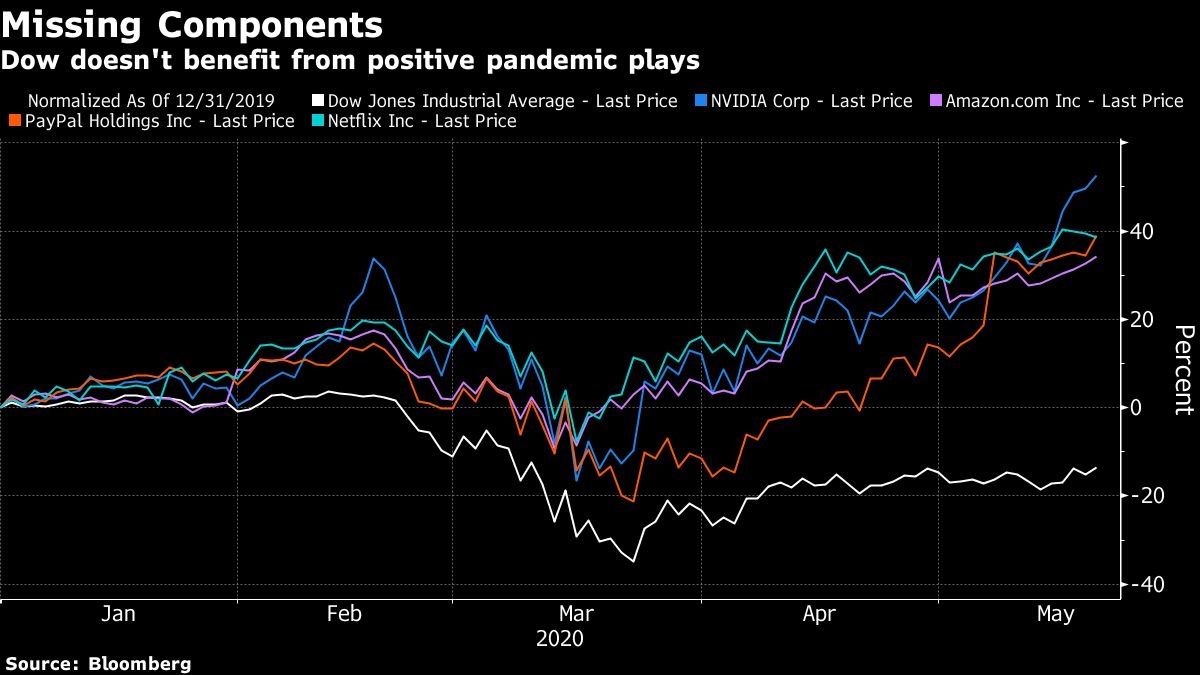

A lot of the discrepancy boils down to which companies don’t make the Dow’s cut. Take Amazon.com, for example, whose 35-per-cent gain this year has accounted for almost half of the Nasdaq’s advance and 10 per cent of the S&P 500’s. Because of the stock’s US$2,500 price tag, the Dow’s old-fashioned price-weighting system makes it impossible to let Amazon in.

Other high-fliers that have proved themselves in a stay-at-home world also don’t appear in the Dow. Nvidia Corp., Netflix Inc. and PayPal Holdings Inc. — all winners in the coronavirus age — are each up at least 30 per cent this year. The venerable Dow has gotten none of that boost.

“If all you’re following is the Dow, you’re missing some big components,” said Ryan Detrick, senior market strategist for LPL Financial. “I hate to say it’s old, but there’s no question that it’s behind the times if you look at the way it’s broken down.”

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, created on May 26, 1896, is different from other indexes. It’s weighted by share price rather than market cap, which is more commonly used today. Such methodology essentially rules out inclusion of several of the largest companies in the world, among them Google parent Alphabet Inc., whose shares trade above US$1,000 and would likely take up too much of the index.

A committee chooses members, not an objective, rules-based process. According to Dow Jones Averages methodology papers found on its website, the Dow seeks to maintain “adequate sector representation” and favors a company that “has an excellent reputation, demonstrates sustained growth and is of interest to a large number of investors.”

As a result, a company like jet-maker Boeing Co., down 60 per cent this year, is more influential on the Dow’s performance than even the fourth largest American company, Alphabet, is on the S&P 500’s returns. Industrial firms, as the name of the index suggests, make up a notable 13 per cent of the Dow — five percentage points more than the sector’s weight in the S&P 500 and 11 percentage points more than the Nasdaq.

Such focus has hurt in a pandemic-arranged stock market, where closed factories and shuttered economies have left industrials as one of the worst performing groups. The emphasis on the old-age economy is all the more striking in a world where companies that can operate with little face-to-face contact excel and a technological shift is accelerated.

“That’s the unique nature of this particular recession, and it’s coming from the virus,” said Luke Tilley, chief economist at Wilmington Trust Corp. “If you take those contours of both big companies tend to have a buffer because of their access to capital markets and then you compound what is expected to be a dramatic change to the economy, you can get that bifurcated performance.”

That leaves another way to view the index gap: the Dow is perhaps the stock gauge that is most representative of the broad economy precisely because it’s not dominated by these megacap firms. Surging shares of Amazon or Netflix certainly don’t reflect an America with over 20 million people unemployed and a collapse in spending.

While the S&P 500 and Nasdaq may be methodologically optimized for a stay-at-home world, the Dow is certainly not.

“Covid is actually amplifying all types of inequalities in the economy but the inequality in the market in terms of market concentration is also being amplified,” said Nela Richardson, an investment strategist at Edward Jones. “That rally is highly concentrated in a handful of firms. Most firms are still in bear territory.”