Nov 27, 2022

The Economic Reality of Life Outside the EU: Brexit in Charts

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Brexit barged its way back onto the UK political agenda this month, with a report that Rishi Sunak’s government might seek closer ties with the European Union.

Both the prime minister and his chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, denied they are seeking a Swiss-style deal, and opposition Labour Party leader Keir Starmer also rejected the idea. They insist their priority is to make the Brexit deal signed in 2020 work.

But polling reveals mounting regret among the British people who voted to leave the EU in 2016, largely due to concerns about the economy. In recent days, a former Bank of England rate setter and the government’s own forecaster warned of a permanent hit to growth.

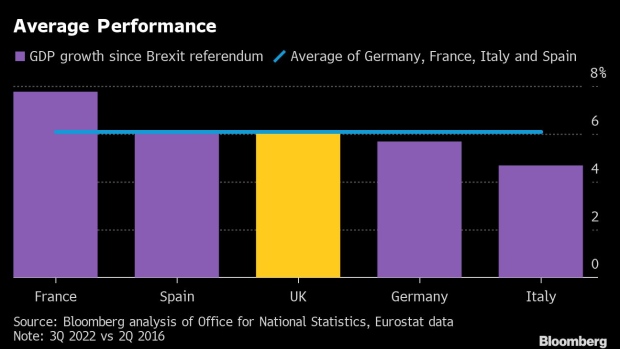

But how has Britain actually fared in the last six years relative to other major industrial nations, particularly its largest EU peers: France, Germany, Italy and Spain?

GDP

Mark Carney, the former BOE governor, claimed earlier this month that the UK had shrunk from 90% the size of the German economy to 70% since Brexit.

The claim was quickly discredited, however, as he was comparing the two economies in dollar terms at a time when the pound was particularly weak. Jonathan Portes, professor of economics at King’s College London who opposed Brexit, called it “nonsense.”

Total real growth since the second quarter of 2016 has been stronger than in Italy and Germany. On per capita GDP, the UK has grown roughly in line with Germany and Spain.

As national income is the broadest measure of economic performance -- capturing the aggregate impact of investment, trade, employment and other factors -- it is the most important. Since Brexit, the UK has effectively held its own.

Most economists accept that the economy will suffer in the long term, though.

The Office for Budget Responsibility assumes a 4% permanent hit, some of which has already been incurred. The estimate is based on border frictions reducing trade intensity and business investment weakens, weighing on productivity. Both appear to be happening.

The OBR also assumes lower migration will slow labor supply, which reduces potential output. That looks more questionable.

On Thursday, Hunt contested the OBR’s estimate. A group of pro-Brexit economists recently pointed out that the 4% is an unscientific average of 13 independent studies. Those estimates range from damage of 1.8% of GDP to 10% of GDP.

Sterling

Sterling has fallen 12.5% against the trade-weighted basis since the referendum, 19% against the dollar and 11% against the euro.

Simon French, chief economist at Panmure Gordon, said: “The pound has faced a sustained devaluation since 2016. Most of this was a downward move post-referendum that has never recovered. This makes UK economic output less valuable and amplifies imported inflation.”

Household income

The depreciation has lifted UK inflation relative to other countries, meaning Britain has suffered a steeper fall in living standards. Real household disposable income, a measure of people’s lived economic experience rather than notional output, has trailed all four major EU peers except Spain.

Employment

The UK has the second-lowest unemployment rate of the largest EU economies after Germany. Job creation has consistently been stronger than in the EU, with the UK’s flexible labour market often cited as a reason.

Lately, the UK has faced acute labor shortages which are forcing businesses to raise wages and close. The scarcity, caused by the loss of around half a million people from the workforce since early 2020, are a legacy of the pandemic and primarily due to people retiring or becoming too ill to work.

Migration

Taking back control of Britain’s borders was a central Brexiteer pledge during the referendum campaign. Free movement of labor with the EU ended in December 2020 but control has not reduced numbers.

The latest official data shows net migration in the year to June 2022 hit a record 504,000, inflated by settlement schemes for Afghans, Ukrainians and migrants from Hong Kong. A year earlier, during the pandemic, migration was 173,000 -- about 75,000 below pre-Covid averages.

While it is now harder for EU migrants to move to the UK, the rules have been relaxed for other nations. All of the net migration in the latest year was accounted for by non-EU migrants. On balance, EU nationals left the country.

Portes says the new regime has turned out to be more open than expected. The OBR concurs and this month raised its long-term estimate of net annual migration from 129,000 to 205,000.

“Overall net migration to the UK appears to be roughly similar to pre-pandemic levels,” Portes said. “Roughly half the jobs in the labor market are open to those coming from anywhere in the world, not just the EU.”

Productivity

The flip side to Britain’s low unemployment rate is its poor productivity. Productivity growth is vital as it determines how quickly living standards can rise. On this key measure, the UK has lagged behind Germany, France and the US for some time.

Before the financial crisis, Britain was catching up -- but that partly reflected the unsustainable boom in banking. Since then, the UK has fallen back and continued to do so after the Brexit vote.

Between 2015 and 2021, Britain lost considerable ground against the US, Germany and France. Some economists have argued the pandemic caused measurement problems, but the UK had already dropped further behind back by 2019.

Investment

Business investment has suffered more than Germany, France and Italy. Uncertainty and political instability during the negotiations with Brussels caused the private sector to slow capital spending in the UK. Investment has lagged all Group of Seven advanced economies since the 2016 referendum.

Inward foreign direct investment offers some encouragement, however. The UK saw more investment from overseas than its EU neighbors in the first half of this year, according to the OECD, even though the massive advantage it previously had has disappeared.

Trade

The most apparent evidence of Brexit damage is in UK trade data. Since the transition period ended on Dec. 31, 2020, Britain has fallen behind other nations in terms of trade intensity – the scale of imports and exports as a share of GDP. Swati Dhingra, a trade expert who sits on the BOE’s Monetary Policy Committee, told lawmakers: “It is undeniable now that we are seeing a much bigger slowdown in trade in the UK compared to the rest of the world.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.