Feb 11, 2019

The European Election Won’t Break the EU

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Just how anti-European Union will the next European parliament be? Latest polls suggest that that populist, often euroskeptic parties, could do well enough in May’s vote to get a disruptive blocking minority – but that would require an improbable degree of cooperation on their part.

Given the difficulty of placing dozens of parties in 27 countries on a single political spectrum and then gauging their strength more than three months before the election, there is, understandably, a range of projections. Then there’s the added complication of matching up how the parties perform domestically with which umbrella groups they join in the European Parliament.

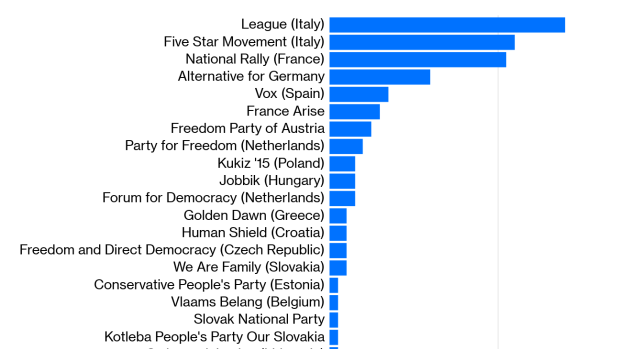

Europe Elects predicts that the three grouping uniting various flavors of populism and euroskepticism – Europe of Nations and Freedoms (ENF), Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy (EFDD) and European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) – should win 176 seats out of the total of 705 left after Brexit.

But that excludes Hungary’s ruling Fidesz party, which is a member of a more mainstream center-right faction, and its far-right rival Jobbik, which is unaligned on the European level. If you add those two, the populists would gain another 15 seats, bringing their share to 27 percent, up from 22.5 percent in the current parliament. That still leaves open the question of what grouping a rising star like Spain’s Vox party will join, let alone what Italy’s erratic Five Star movement may decide.

Susi Dennison and Pawel Zerka of the European Council on Foreign Relations analyzed the data at the national level – probably the better method, for now – using Jan. 3 data from Poll of Polls, a Vienna-based aggregator. In a report published this week, they predicted that more than a third of seats in the parliament could go to “anti-Europeans” – a charged term. For Dennison and Zerka, it refers to members of the extreme left as well as populist, nationalist movements.

If you plug the latest Feb. 11 data from Poll of Polls into their model, and then add other populist-tinged parties such as Poland’s ruling Law and Justice (PiS) party, Fidesz, the Sweden Democrats and Belgium’s New Flemish Alliance, the grand total of “anti-Europeans” from both left and right would come to about 220, close enough to a third of all seats in the parliament, which would be necessary for qualitative change.

It would be enough to block the EU’s efforts to punish Hungary and Poland for undermining the rule of law. The parties would be able to stop committees rubber-stamping appointments to the European Commission. They could even play a key role in shaping the EU’s budget – if the mainstream parties can’t unite (a likely scenario).

Serious disruption would be possible if all the extreme forces formed what the ECFR report describes as an “‘all against the establishment’ alliance of the far right, euroskeptics, and the far left.”

Dennison and Zerka point out that anti-establishment forces have cooperated in the European Parliament on some issues before: “Love of Russia, hatred of sanctions, and strong protectionist inclinations can unite the far left and the far right,” they argue. An alliance wouldn’t need to be formal, or even stable: “unplanned alignment” in key votes would be enough to make the mainstream parties’ control of the European Parliament precarious, forcing them to build coalitions to a degree that hasn’t been necessary.

Even if the populist parties fail to win enough seats to swing key votes, the nationalist ones among them are already shaping the pre-election debate. Immigration is a key issue in almost all EU member states. Mainstream parties have had to engage, and are in the unenviable position of explaining complicated matters to voters while the populists bombard them with simple slogans.

The ECFR report recommends that the centrists make the election about other issues – European values, tax justice, climate change, or the Kremlin’s attempts to undermine the EU. I doubt, though, that any of these have the electoral potency of immigration.

In the election, however, complexity isn’t just the political center’s enemy – it can also help. Putting diverse parties from different countries into baskets such as “anti-Europeans,” “far right” or “anti-establishment,” as the ECFR has done, can be overly simplistic. Many of these groups on the fringe of the political spectrum aren’t really opposed to the EU and aren’t calling for their countries to pull out of it; some would like a less empowered EU, but that’s part of a legitimate discussion – not necessarily an attack on European values.

Mental experiments like imagining ad-hoc anti-establishment coalitions can be useful for more than scaring centrists into greater cooperation. They also show the depth of the divides between the forces unhappy with the status quo. For them, winning seats in the European Parliament can be a useful reality check; some – such as Greece’s Syriza or Spain’s Podemos, not to mention Fidesz – have found it more natural to vote with the center than with the nationalist fringe on many issues.

I find it hard, then, to work myself into a state of fear about the election. Even if the various anti-establishment parties do get the number of seats the polls suggest, the European project looks safe.

To contact the author of this story: Leonid Bershidsky at lbershidsky@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is Bloomberg Opinion's Europe columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.