Jul 19, 2019

The Fed Cherry-Picked Its Way to a Rate Cut. Here’s Proof.

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The Federal Reserve has resorted to fallacy.

After the central bank’s June meeting, policy makers indicated that the case for easing monetary policy had grown but that they wanted to wait to see further evidence of weakening data before lowering interest rates. U.S.-China trade tensions were certainly a risk, but as Chair Jerome Powell noted on June 25, a week after the central bank’s decision, “the amount of tariffs that are in place right now is not large enough to represent a major — from a quantitative standpoint — threat to the economy. The concern is about confidence and financial market ripple effects.”

Fast-forward to the present, and you’d hardly recognize that patient, prudent stance. Bond traders in the past 24 hours have rapidly moved toward pricing in not just an interest-rate cut at the end of the month, but a steep, 50-basis-point reduction. New York Fed President John Williams and Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida tag-teamed to jolt the market odds before the central bank’s self-imposed blackout period begins. Williams said that “when you only have so much stimulus at your disposal, it pays to act quickly to lower rates at the first sign of economic distress.”(2)

Where’s the economic distress, exactly?

Powell has cited “crosscurrents from global growth and trade” as potentially reverberating onto the U.S. economy. But there’s scant evidence of that happening on a large scale. He said he was watching to see whether tariffs would hurt confidence and financial markets. But a Bloomberg index of expectations for the American economy is the highest since November. The S&P 500 Index is near record levels. High-yield corporate bond spreads are around their one-year average.

The only conclusion I can draw from watching the Fed over the past month is that, at best, officials have resorted to cherry-picking data (or ignoring it entirely) to support their plan to lower interest rates. This is sometimes referred to as the fallacy of incomplete evidence. At worst, the central bank caved to political pressure from President Donald Trump for lower rates and a weaker dollar — a point he hammered home again on Friday as he criticized the central bank’s “faulty thought process.”

To put the Fed’s cherry-picking in stark relief, I selected a handful of U.S. data and compared it collectively with each month since the central bank’s tightening cycle began in earnest in December 2016. I chose the following metrics:

- Change in nonfarm payrolls: Arguably the most-watched number to assess the health of the labor market

- Core Consumer Price Index: Measures the less-volatile components of inflation

- Empire State Manufacturing Index and Philadelphia Fed Business Outlook: Both are considered good cyclical indicators

- Retail sales: A closely watched figure for retailers and wholesalers, as well as consumer spending

- Markit Manufacturing and Services PMIs: Gauges of the industrial and services parts of the economy

Every single one of these measures, when released in the past three weeks, beat analysts’ estimates.(1)That has never happened in a month going back to the end of 2016. It’s a stunning contrast to the baked-in expectations that the Fed will cut by at least a quarter-point, and quite possibly more, because the economy needs a boost.

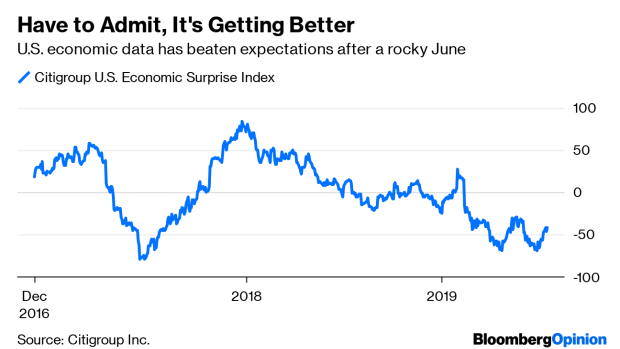

Am I cherry-picking a bit myself? Perhaps. Housing starts and building permits came in weak, for one, and average hourly earnings were an ever-so-slightly disappointing part of the jobs report. But overall, the data has certainly improved since the Fed’s last meeting, captured succinctly by U.S. economic surprise indexes from Citigroup Inc. and Bloomberg, both of which are at the highest since early June.

How do top Fed officials explain themselves in the face of this flurry of stronger-than-expected economic figures? They now appear content to simply abandon the pretense of data dependency. Clarida remarked that “you don’t need to wait until things get so bad to have a dramatic series of rate cuts,” adding that research favors acting preemptively. He emphasized “disappointing” global data, while calling U.S. data “mixed.”

As I wrote last week, a rate cut this month was never in doubt after Powell’s congressional testimony, which made every effort to highlight risks to the U.S. economy, however small, and areas where it’s doing worse than expected. He could have quite easily left the door open to keeping policy steady, especially after the rebound in the jobs data — in fact I laid out the path to doing so here — but he instead decided it wasn’t worth the effort.

That’s too bad. For the Fed to maintain credibility, Powell is going to have to explain at his press conference after the July decision whether the central bank’s reaction function has changed. Because this abrupt change in the span of just a few months, from holding steady to potentially a shocking 50-basis-point cut, tests the limit of plausibility. It certainly seems as if officials are much more focused on comparing their policy to others around the world.

I still think the most likely outcome is a consensus quarter-point cut on July 31. In fact, the aggressive commentary from Clarida and Williams could be seen as a way to move the goal posts and make a “smaller” rate cut seem like the patient and prudent way to handle monetary policy — effectively pulling off a “hawkish surprise” and an interest-rate cut at the same time. Indeed, Citigroup Inc. strategists were among those who rushed to adjust their call to a 50-basis-point drop in rates mere hours after the Fed duo moved the markets. Others expect the same.

It’s important for bond traders to see through this shift and understand its implications. The Powell Fed of old is no more. Nothing fundamentally has changed in the U.S. economy in recent months, and yet the most influential members of the central bank are clearly determined to ease policy. Whatever the opposite of data-dependency is, that’s what’s driving interest-rate decisions now.

(1) A New York Fed spokesman later said the following: "This was an academic speech on 20 years of research. It was not about potential policy actions at the upcoming FOMC meeting."

(2) For those of you who take issue with using CPI over the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the most recent reading of the core personal consumption expenditures index also topped forecasts when released on June 28.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.