Mar 29, 2022

The Fed has made a U.S. recession inevitable

Fed may tighten too fast: D. Alexander Capital’s Larry Shover

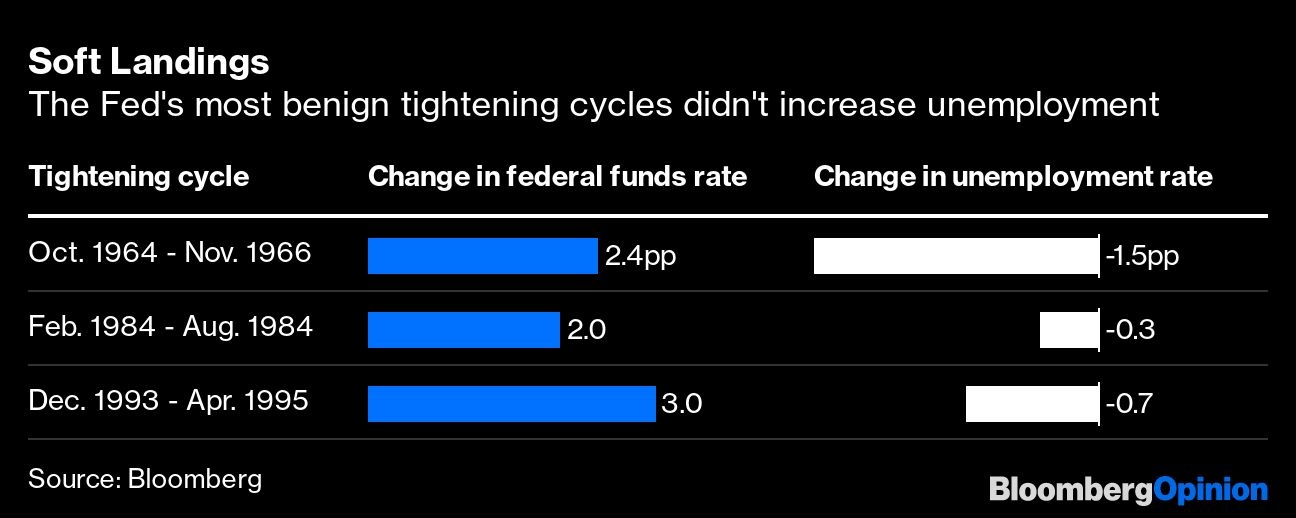

U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has made two ambitious assertions about the central bank’s management of the economy. In his latest news conference, he said that the Fed’s new, more inflation-tolerant monetary policy framework bears no responsibility for the recent sharp surge in consumer prices. Then, the following week, he cited three historical examples — the tightening cycles of 1964, 1984 and 1993 — as evidence that the Fed can achieve a “soft landing,” slowing growth and curbing inflation without precipitating a recession.

I disagree with both. The Fed’s application of its framework has left it behind the curve in controlling inflation. This, in turn, has made a hard landing virtually inevitable.

Under the monetary policy framework, introduced in August 2020, the Fed is supposed to target average annual inflation of 2 per cent, which means allowing for occasional overshoots to make up for previous shortfalls. Yet in the current recovery, the central bank translated this into a more specific commitment. It would not start to remove monetary stimulus until three conditions had been met: inflation had reached 2 per cent; inflation was expected to persist for some time; and employment had reached the maximum level consistent with the 2 per cent inflation target.

This was a mistake. As I wrote last June:

This means monetary policy will remain loose until overheating begins – and cooling things off will require the Fed to increase interest rates much faster and further than it would if it started raising rates sooner. […] The delay in lifting off, for example, is likely to push the unemployment rate considerably below the level consistent with stable inflation, increasing the odds that the Fed will need to tighten sufficiently to push the unemployment rate back up by more than 0.5 percentage point. Over the past 75 years, every time the unemployment rate has moved up this much, a full-blown recession has occurred.

This scenario is playing out now. The labor market is “extremely tight” (Powell’s words), inflation is running far above the Fed’s objective and the central bank is only beginning to remove extraordinary monetary accommodation. Powell blames bad luck — surprises such as snarled supply chains that officials could not have anticipated. To some extent he might be right, but the Fed nonetheless bears responsibility for being so slow to recognize the inflation risks and begin to tighten policy.

So can the Fed correct its mistake and engineer a soft landing? Powell is correct that the central bank tightened monetary policy significantly in 1965, 1984 and 1994 without precipitating a recession. In none of those episodes, though, did the Fed tighten sufficiently to push up the unemployment rate.

- 1964: The federal funds rates rose from 3.4 per cent in October 1964 to 5.8 per cent in November 1966, while the unemployment rate declined from 5.1 per cent to 3.6 per cent.

- 1984: The federal funds rate rose from 9.6 per cent in February to 11.6 per cent in August, while the unemployment rate declined from 7.8 per cent to 7.5 per cent.

- 1993: The federal funds rate rose from 3 per cent in December 1993 to 6 per cent in April 1995, while the unemployment declined from 6.5 per cent to 5.8 per cent.

The current situation is very different. Consider the starting points: The unemployment rate is much lower (at 3.8 per cent), and inflation is far above the Fed’s 2 per cent target. To create sufficient economic slack to restrain inflation, the Fed will have to tighten enough to push the unemployment rate higher.

Which leads us to the key point: The Fed has never achieved a soft landing when it has had to push up unemployment significantly. This is memorialized in the Sahm Rule, which holds that a recession is inevitable when the 3-month moving average of the unemployment rate increases by 0.5 percentage point or more. Worse, full-blown recessions have always been accompanied by much larger increases: specifically, over the past 75 years, no less than 2 percentage points.

The Fed needs to adjust how it puts its monetary policy framework into practice. It shouldn’t be completely reactive, waiting passively until inflation exceeds target and the labor market is extremely tight. Such extreme “patience” forces it to slam on the brakes, increasing the likelihood of an early recession. Also, officials need to be more forthright about the road ahead: Getting inflation down will be costly, in terms of jobs and economic growth.