Jul 22, 2019

The Fed has reached a turning point

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. Federal Reserve is poised to put interest rates on a new, downward trajectory in its efforts to support an increasingly fragile economy. The move is long overdue, but it’s crucial that officials and the public recognize the risks.

Although Fed officials meet at least eight times a year to deliberate over monetary policy, they change the direction of interest rates much less frequently. The past fifteen years can be divided into three distinct phases (with a few short “wait and see” gaps): tightening from June 2004 through August 2006, easing from September 2007 through December 2012, and tightening again from June 2013 to December 2018. The Fed didn’t move at every meeting in these periods, but the overall tilt of policy was clear.

Now, the central bank has reached another turning point. At their next meeting on July 31, officials are very likely to respond to persistently low inflation and global trade risks by cutting interest rates for the first time in more than 10 years. On its own, such a move is of little importance to the economy. But if history is any guide, it will mean that the Fed is highly unlikely to be willing to raise rates for the next twenty-five to fifty meetings. That is a big deal.

If it makes the switch to easing, the Fed will be signaling a great deal of confidence that inflation will remain subdued for the next couple years or even longer. Personally, I think that’s right. But it’s important to recognize that this view is largely grounded in a “the next few years will look like the past few years” approach to forecasting. That approach is often correct, but not always!

Another question is how far the Fed will go. I’m expecting nothing more dramatic than a quarter percentage point cut at next week’s meeting. As I noted, the central bank prefers to change direction only rarely: If it wants to avoid getting into a position where it will suddenly have to raise rates, its steps downward will have to be smaller. I think a second quarter-point cut will come later this year, probably in December.

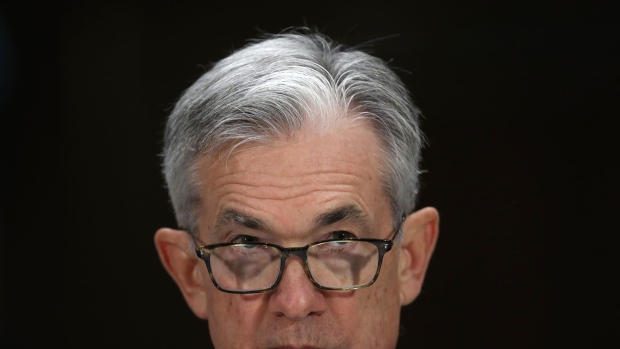

Given the significance of next week’s decision, how the Fed makes and communicates it matters a lot. The policy-making Federal Open Market Committee has convened eleven times under Chairman Jerome Powell, but only once has a member dissented. That degree of consensus is somewhat troubling: Is the Fed really hearing all possible perspectives on a rather complicated economic situation? I would hope and expect that one or two members will dissent if the committee decides to lower rates. The move certainly presents inflationary risks, and the public should know about them.

I’ll be glad to see the Fed finally beginning to ease. As early as 2015, when I was still president of Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, I suggested that an interest rate cut would be appropriate. I hope that it won’t be too late, and that Fed officials keep their eyes wide open to what could go wrong.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Narayana Kocherlakota is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a professor of economics at the University of Rochester and was president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from 2009 to 2015.