Jan 29, 2019

The Fed's balance sheet is misunderstood

, Bloomberg News

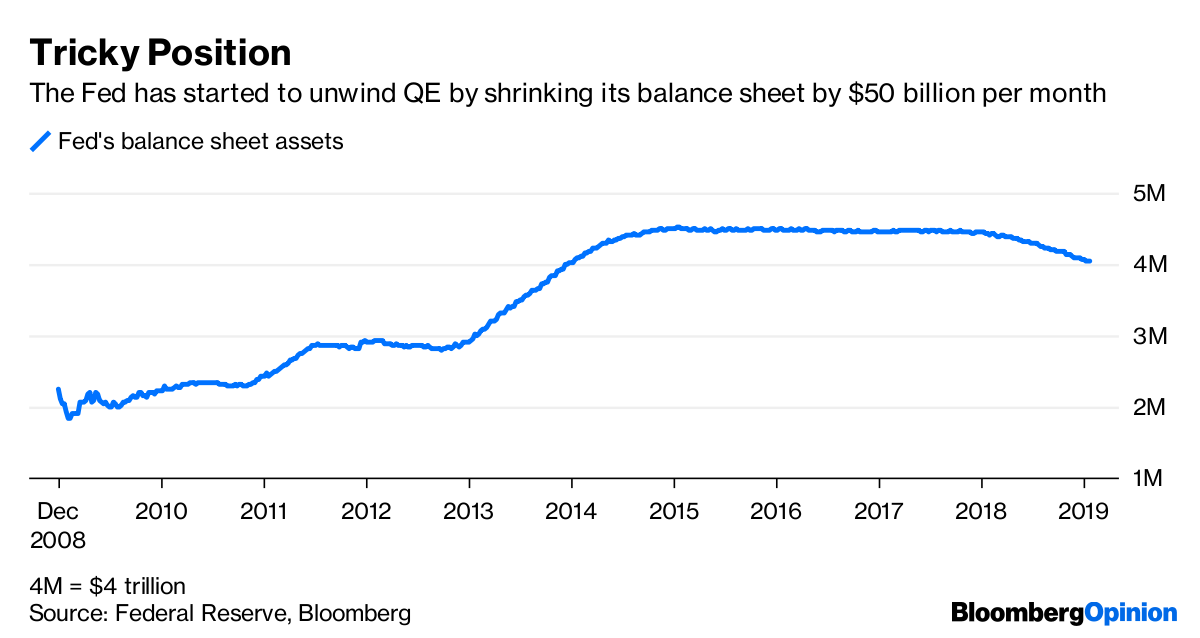

The Federal Reserve finds itself in a tricky position with its balance sheet policy. Years of bond purchases via quantitative easing caused the central bank’s assets to swell from less than US$1 trillion in 2008 to US$4.5 trillion by the end of 2014 in an effort to provide financial accommodation to the economy.

But now that the Fed has started to shrink those assets, to about $4 trillion as of last week, it is having a hard time convincing market participants that central bankers expect the ultimate size of the balance sheet will be primarily determined by technical rather than economic conditions. Hence, a slowing or cessation of a reduction in the balance sheet would not necessarily imply the Fed is worried about the economy. Such worries would likely first result in a change in interest-rate policy.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the Fed turned to QE to inject cash into the markets to ease financial conditions and support the economy after their primary policy tool, short term rates, fell to zero. QE is now part of the Fed’s policy toolkit, but one it wants to use sporadically. As such, the shift away from using its balance sheet as a policy tool has been something of a challenge.

The Fed expected that shrinking its balance sheet assets by as much as $50 billion per month would be as boring as “watching paint dry.” Rather than relying on the balance sheet to impact economic activity, they want to instead implement policy via the expected path of short term rates. The ultimate size of the balance sheet thus depends on the amount of reserves the Fed thinks is necessary to effectively control rates.

The Fed is falling short in communicating the difference between using the size of the balance sheet as a policy tool versus the size of the balance sheet being only relevant as far as it allows them to implement policy via interest rates. This communication challenge became most evident at the press conference that followed the December 2018 Federal Open Market Committee meeting when Fed Chairman Jerome Powell dismissed the idea of slowing the pace of balance sheet reduction, triggering a fresh downturn in stocks.

Powell (and other policy makers) subsequently made clear that the Fed would change their plans if the balance sheet wind down was having a deleterious impact on the economy. Still, they don’t believe that such impacts are occurring. See, for example, that such concerns disputed by Atlanta Federal Reserve President Raphael Bostic.

Where does this leave us? First, it is very unlikely that the Fed will turn to the balance sheet at the first sign of trouble for the economy. Yes, Powell opened the door to such a response but I would expect that the Fed would first turn toward its interest rate tools. The Fed would find this the preferable approach as it would meet the Fed’s goals of transmitting policy via rates when policy is away from the zero lower bound.

Second, I would not interpret a decision to slow or even end balance-sheet reduction as a signal that the Fed is worried about the economy or intends to take a more accommodative policy stance. Central bankers worried about such an interpretation in the minutes from the December 2018 FOMC meeting.

Remember, the Fed doesn’t know exactly what will be the ultimate size of the balance sheet consistent with effective control over short term rates. Some participants in the last FOMC meeting suggested that the Fed should slow the balance sheet wind down as they move closer toward the ultimate end point for the balance sheet. Such a shift would reflect the technical considerations to reduce volatility in short term rates rather than monetary policy.

Ultimately, the Fed will likely continue to focus on interest rates as its main policy tool and, as long as the economy holds away from the zero bound, attempt to de-emphasize the balance sheet as largely a technical issue. Don’t expect the Fed to turn to the balance sheet if the economy stumbles and recognize that they may slow or end the balance sheet reduction even if the economy stays strong. In other words, until the Fed believes that balance sheet reduction is itself creating too much financial tightening, the Fed’s decisions about the balances sheet will hinge largely on technical issues rather than the state of the economy.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tim Duy is a professor of practice and senior director of the Oregon Economic Forum at the University of Oregon and the author of Tim Duy's Fed Watch.