Jun 24, 2019

The Internet Is Everywhere, But Internet Jobs Aren’t

, Bloomberg News

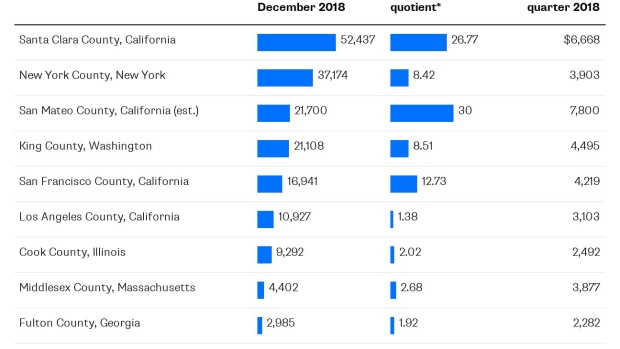

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The internet was supposed to render geography irrelevant.(2) But the corporations that dominate the internet have turned out to be remarkably concentrated, geographically speaking. In internet publishing and web search portals, a somewhat ungainly but very important North American Industry Classification System category, 58% of all U.S. jobs in December could be found in just five counties, and more than 70% in the top 10.

The location quotient is a measure of how concentrated an industry is in a particular place — a quotient of 1 means it’s right at the national average — and the location quotients in the above table make clear that this particular industry is heavily concentrated in the top five counties, especially the three bordering San Francisco Bay. In San Mateo County, home of Facebook Inc., one is about 30 times more likely to encounter an internet publishing and web search portal employee than in the country in general. Just to the south in Santa Clara County, the heart of Silicon Valley and the home of Google and its corporate parent Alphabet Inc., it’s 27 times more likely. Just to the north in San Francisco County, home of Twitter Inc. and Pinterest Inc., it’s 13 times more likely. The Bureau of Labor Statistics actually didn’t release fourth-quarter San Mateo County data for the sector, presumably because it was so dominated by Facebook that this would amount to disclosing private information, so I backed out the numbers using metropolitan-area data and a little elbow grease. The BLS did release San Mateo County numbers for the third quarter, and the employment total and location quotient were close to those I came up with (the average weekly wage was higher, at $8,872), so I don’t think this was much of a stretch.

Related: Where Microbrewery Jobs Are OverflowingFinancial Jobs Aren’t Just in New YorkA Booming Local Health-Care Industry Isn’t Always a Good Thing

Employment location quotients of 30 and 27 are, it should be stressed, quite high, especially for such populous counties (San Mateo County has about 770,000 inhabitants; Santa Clara County nearly 2 million). Wayne County, Michigan, the headquarters of the U.S. automobile industry, had a December employment location quotient for motor vehicle manufacturing of 16.7; the District of Columbia’s location quotient for federal government employment was 13 and change.

Santa Clara County did have a dizzying December location quotient of almost 64 for electronic computer manufacturing (thanks mainly, one assumes, to Cupertino-based Apple Inc.) and 40 for semiconductor machinery manufacturing (industry leader Applied Materials Inc. is based in the city of Santa Clara), but those are at least industries that revolve around creating complex, tangible products, which it stands to reason necessitates lots of people working in the same place. The internet is on first impression different: It’s everywhere, and it can be worked on from anywhere. Yet employment at the corporations that shape it is concentrated in a handful of places in the U.S. and has been getting more so. In March 2014, the top five counties accounted for 48% of the nation’s internet publishing and web search portal jobs, and the top 10 62%.

Facebook and Google have been expanding overseas, so it’s possible that this focus on U.S. data is somewhat misleading — sadly there’s no global counterpart to the hyper-detailed Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages from which the data in this column (as well as pieces over the past few days on breweries, financial services and health care) is taken. Also, it’s not all about engineers at Facebook and Google: As the lower average wages outside of Silicon Valley indicate, this category also includes journalists working at online enterprises such as BuzzFeed Inc. and Vox Media Inc. in New York and elsewhere. It may also include contract workers slowly going crazy moderating Facebook pages in Phoenix; it’s often hard to know for sure how specific corporate activities are classified by the BLS, because the BLS isn’t allowed to say, but the goal is to assign the people working at a location to the industry sector that best fits what most of them are working on.

Traditional media has a tendency toward concentration, too: Los Angeles County has 27% of the nation’s jobs in motion picture and sound recording industries. New York County (aka Manhattan) has 18% of all U.S. periodicals publishing jobs. The two counties together account for 20% of broadcasting employment. But the top-five and top-10 counties’ shares of jobs in these sectors are much smaller than with internet publishing and web search portals, and in motion pictures and periodicals, the very top counties have actually been losing employment share in recent years as media companies shift production to less expensive locales.

In their much-cited 2009 review of what drives economic activity and the resulting wealth to “agglomerate” in certain cities, economists Edward Glaeser and Joshua Gottlieb wrote that:

The largest body of evidence supports the view that cities succeed by spurring the transfer of information. Skilled industries are more likely to locate in urban areas and skills predict urban success. Workers have steeper age-earnings profiles in cities and city-level human capital strongly predicts income. It is possible that these effects will be reduced by ongoing improvements in information technology, but that is not certain and has not happened yet.

It’s presumably the value of this transfer of information among skilled workers that has driven internet companies to concentrate in a few places. High costs in those places and those “ongoing improvements in information technology” might drive dispersion, although there’s no sign of that yet in this data. Politics might, too: As Facebook in particular has been discovering lately, having your employees concentrated in a few places can mean having few friends in Washington. But for now, the work of internet publishing and web search portals remains tightly clustered along the San Francisco Bay, and to a lesser extent the Hudson River and Puget Sound. Geography still seems to matter, a lot.

Coming Tuesday: the sectors with the highest location quotients.

(1) I realize that this has become something of a straw man, and that by this point far more has been written attacking the idea that the internet renders geography irrelevant than espousing it. But as someone who was at least halfway paying attention in the 1990s, I think it's fair to say that most people in those days assumed that universal connectivity would lead to a spreading out of economic activity rather than a concentration.

To contact the author of this story: Justin Fox at justinfox@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.