Apr 25, 2022

The Long Shadow of Germany’s Top Putin Ally Is Hemming in Scholz

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is struggling to escape the shadow of his predecessor Gerhard Schroeder’s ties to Russia and that’s hampering efforts to help Ukraine.

Germany’s most-recent Social Democratic leader before Scholz, Schroeder, 78, has become a touchstone of controversy 17 years after losing power to Angela Merkel, revealing deeper issues at the heart of the left-leaning party.

In comments to the New York Times published Saturday, Schroeder defended Vladimir Putin and rejected calls to quit his high-paying jobs for state-owned Russian companies. The SPD, which has a long tradition of seeking rapprochement with Russia, hit back on Monday asking him to leave the party and saying a process was underway to expel him.

“His defense of Vladimir Putin against claims of war crimes is simply absurd,” co-leader Saskia Esken said in Berlin, referring to Schroeder’s assertion that he didn’t think orders over the atrocities in Bucha could have come from the Russian leader. “The party is united in its stance toward Schroeder.”

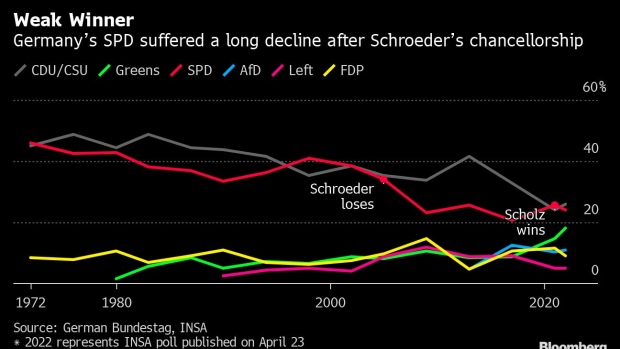

What the spat highlights is just how weak Scholz is as leader of Europe’s largest economy. Despite his remarkable election victory in September, the 63-year-old has only limited control over his party, which remains conflicted in its response to the war in Ukraine. Some SPD members oppose military action, while others still support engaging with the Kremlin.

“The divisions within the SPD act as a constraint on Scholz’s room for maneuver,” Naz Masraff, director for Europe for consultancy Eurasia Group. These internal party tensions have “paralyzed the government.”

Early in the war, Scholz went out on a limb by shipping mainly defensive weapons to Ukraine such as anti-tank and anti-aircraft systems and setting up a 100 billion-euro ($108 billion) fund to upgrade aging military equipment. His party may have been pushed about as far as it can go for now, and Scholz is aware of those limits, according to a person familiar with his thinking.

His “sea change” in Germany’s defense policy has since stalled, as Scholz walks a fine line between international commitments and not straying too far from his party. He’s come under heavy criticism by balking at delivering tanks and other heavy weapons to Ukraine, citing fears of “nuclear war.”

Instead, he’s proposed a complex plan to get eastern European partners to send Soviet-style gear to Ukraine in exchange for more modern replacements paid for by Germany. While it’s unclear to what extent he’s responding to party issues, there is reason for caution if he wants to avoid the same fate as Schroeder.

Schroeder’s defeat to Merkel in 2005 was triggered by disgruntled SPD lawmakers. The left-leaning party helped bring about an early national election due to deep divisions over a series of labor reforms, which Scholz helped push through as the SPD’s general secretary until both and Schroeder stepped down from their party posts in 2004.

The internal conflicts persisted and contributed to Scholz losing his bid to lead the party in 2019 because he was seen as too moderate and too close to the Schroeder reforms. His candidacy in last year’s election stemmed from a lack of viable alternatives rather than a change of heart.

There’s also a division between the government and parliamentary lawmakers. In Scholz’s case, this is even more acute, requiring support from figures such as SPD caucus leader Rolf Muetzenich from the party’s left wing to pass legislation including the defense fund. Scholz’s legislative exposure was evident after his push for a Covid-19 vaccine mandate failed this month.

Despite tensions, Germans largely support Scholz’s cautious line as things stand. A poll by INSA for Bild newspaper shows that 50% are against delivering heavy weapons to Ukraine -- with SPD resistance slightly stronger at 55%. But it’s a thin margin, and pressure will remain high.

The main opposition conservative bloc is seeking a motion this week on delivering tanks to Ukraine. It’s hoping for support from the Greens and the Free Democrats, Scholz’s coalition partners, who have been more aggressive in calling for support for Ukraine’s defense.

For his part, Scholz has tried to distance himself from Schroeder. In early March, he urged the former chancellor to give up posts as chairman of state-owned Russian oil giant Rosneft PJSC and head of the shareholder committee of Nord Stream AG, which built a Russia-to-Germany natural-gas pipeline that Scholz halted.

But Schroeder has been a recurring theme of Scholz’s short tenure. In February, with Scholz under pressure for not standing up more robustly to Putin’s aggression, he waved off Schroeder’s allegations that Ukraine was “saber-rattling,” defensively asserting: “There’s only one chancellor and that’s me.”

Other senior SPD officials have also been labeled as Kremlin sympathizers including Frank-Walter Steinmeier, Germany’s president and a former foreign minister.

Esken -- who met last week with Ukraine’s ambassador to Germany after a spat over his criticism of the party -- insisted there’s a clear stance on the Kremlin, but acknowledged the SPD may have made mistakes about Russia in the past.

“The SPD doesn’t have a Putin problem,” she said in Berlin. But as Moscow developed its expansionary ambitions over the past 20 years, “we possibly saw those warning signs too late.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.