May 13, 2022

The Multibillion-Dollar Risk Driving Big Banks Away From SPACs

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- As an army of blank-check companies gathered $250 billion on their march to public stock markets over the past two years, banks handling the fundraisings earned windfalls and lavished star dealmakers with some of their firm’s largest bonuses.

But this year, many of those special-purpose acquisition vehicles, or SPACs, are struggling to seal the deals that are their reason for being -- merging with private companies. And this month, top banks including Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Bank of America Corp. pulled back from helping them hunt for targets.

The problem: US regulators proposed holding banks liable if the SPACs or their businesses mislead investors.

Behind the scenes, Wall Streeters are hastily reevaluating one of their most lucrative activities in recent years. Some are concluding that helping a SPAC stage an initial public offering and later merge with a private company is poised to become too complex and risky, potentially creating massive liabilities. As frustrated bankers see it, they’re essentially being told to follow the rules for IPOs and mergers simultaneously, while the government makes it easier for shareholders to sue if deals don’t work out.

“The magnitude of the exposure could be potentially enormous,” said Howard Suskin, co-chair of Jenner & Block’s securities litigation and enforcement practice. “All the plaintiffs have to show is that there was something incorrect that was said in the offering documents.”

To Securities and Exchange Commission Chair Gary Gensler, the fault lies with banks for thinking they could usher private companies’ into public markets without a duty to ensure shareholders get accurate information. After all, that’s the role of banks handling more traditional initial public offerings.

“The core concept of a traditional IPO is that there’s a gatekeeper and a gatekeeper has a certain set of responsibilities,” Gensler said during an interview with Bloomberg on Tuesday, a day after the news broke that Goldman and Bank of America were pulling back. The SEC has been gathering comments on its proposals for SPACs and has yet to finalize the new rules.

The banks’ retreat follows the rise and fall of the SPAC craze. Once a Wall Street niche, the vehicles came into vogue as the unpredictable pandemic took hold, making it harder to stage traditional IPOs. But in recent months, enthusiasm for SPACs has dissipated, hurt by softening markets and a growing number of prominent deals that fizzled.

Investors have growing reason to complain about SPACs’ performance. Blank-check vehicles announced 186 mergers last year that have since been completed. Of those, 95% are trading below the blank-check firms’ initial price of $10, data compiled by Bloomberg show, saddling investors with billions of dollars in losses. That compares with stock declines at about 76% of companies that held traditional IPOs.

In a traditional IPO, companies don’t typically give financial forecasts because banks underwriting their deals aren’t willing to stomach the risk of lawsuits if predictions don’t come true. But SPAC management teams, known as sponsors, have long made forecasts since the deals are essentially mergers -- sometimes with an optimism that later proves unrealistic.

One examination of SPAC mergers from 2004 through 2021 found that only 35% of firms with post-merger revenue met or beat projections, according to the study’s authors, academics from the University of Washington, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the University of Michigan. SPAC revenue projections were about three times larger than revenue growth achieved by companies that listed via IPOs, according to their paper dated in February.

“There’s a strong temptation to make those forecasts look better than reality because SPAC sponsors benefit so much from closing a deal,” Elizabeth Blankespoor, an associate professor at the University of Washington’s Foster School of Business who co-wrote the research, said in an email. The vehicles likely make such forecasts “because SPACs think there is little punishment if their forecasts are wrong.”

The SPAC boom also enriched individual bankers. A number of firms have been awarding star bankers more than $10 million a year for their work with blank-check firms and other deals, people familiar of the matter said, asking not to be identified discussing private information.

The life cycle of a SPAC begins when sponsors put up a relatively small amount of money and hire a bank to help them hold an IPO, looking to raise much more so they can hunt for a merger. That’s been a fairly low-risk process for bank underwriters, because the SPAC is essentially hollow, with no business to describe. Banks can later earn more by helping the blank-check firm merge with a private company, thus taking it public, in a process known as a de-SPAC. That’s when projections are made.

The total amount earned by banks in both steps of the process is similar to what they get for handling a traditional IPO, but for less work.

The new SEC proposals seek to deter rosy projections by deeming the banks that underwrite an IPO to also be “statutory underwriters” for the de-SPAC, if they help with that part of the process.

“It was inevitable that the SEC would propose these changes,” said Morris Defeo, partner at New York law firm Herrick Feinstein. “Whenever a particular segment of the market gets frothy, the SEC will inevitably want to get involved.”

Signs of froth now abound. Electric carmaker Lucid Group Inc., formed through one of the highest-profile SPAC mergers last year, began trading publicly in July and by November reached a market capitalization of $91 billion. A presentation during its de-SPAC suggested revenue could surpass $22.7 billion in 2026. But amid supply chain woes, it missed one of its initial estimates, generating $27 million of the $97 million in revenue it had forecast for last year. The stock is down 75% from the November peak.

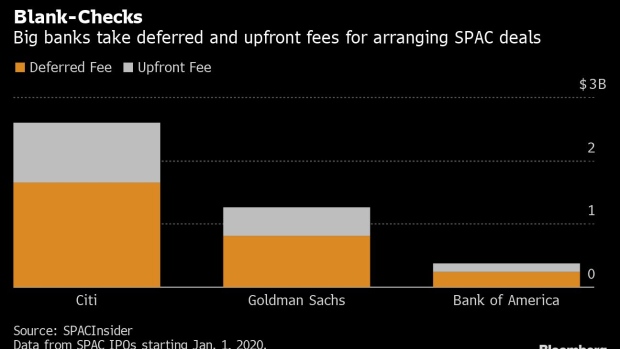

Citigroup Inc. was the lead underwriter for the SPAC that merged with the company, and the bank later advised Lucid on the combination. The lender, which has underwritten well over 100 SPAC listings since beginning of 2021, paused new issuance this year, Bloomberg reported last month. Since January 2020, the bank positioned itself to reap a total of $2.6 billion in upfront and deferred fees, according to SPACInsider.

A representative for Citigroup declined to comment.

Goldman is pulling out of working with most SPACs it took public and pausing new SPAC issuance in the US. Bank of America is scaling back work with some of the deals and may pull out of more. Their retreat from clients yet to complete a de-SPAC could risk that second fee.

Other banks also are adjusting to the SEC’s proposals. Citigroup has become more selective in handling de-SPACs and will turn away clients that don’t subject themselves to stringent due diligence, according to a person with knowledge of its policies. Credit Suisse Group AG added an internal committee to approve SPAC transactions. Both of those banks and others are also seeking comfort letters from auditors assuring that SEC filings made by SPACs don’t contain false statements or factual omissions, people familiar with the matter said.

“Credit Suisse is very selective on the transactions it takes on,” the Swiss bank said in a statement. “We continue to review and improve our approval process around de-SPAC transactions and will continue to comply with all regulations as the SEC rule is finalized.”

SPACs set on finding a merger won’t have it easy. Investor appetite for SPAC deals had long dried up even before big banks retreated. One investor who used to fund several new vehicles a week said he has not bought anything in months. And those that do keep hunting may have to rely on the in-house expertise of their own dealmakers or enlist smaller banks to fill the void.

“Some of the better, more sophisticated, sponsors will get to the finish line,” he said,” said Michael Auerbach, founder of Subversive Capital, who served as chairman of two named SPACs that closed last year. But “a large percentage of the SPACs currently searching for deals will expire before they are able to get a deal closed.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.