Aug 14, 2019

The Push to Help YouTubers of the World Unite

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Why exactly is a German metalworkers union teaming up with YouTubers to take on Google?

The answer has as much to do with concerns over how to organize labor in the era of digital disintermediation as it does with teenagers uploading clips of themselves playing Minecraft.

IG Metall, whose 2.3 million members make it Europe’s largest trade union, joined forces last month with an unlikely ally: the German YouTuber Joerg Sprave, whose Slingshot Channel boasts 2.2 million subscribers and who produces viral videos of himself firing off, among other things, Ikea pencils. Two years ago, he set up a Facebook group called The YouTubers Union, which now has 21,000 members, after his videos started getting “de-monetized” -- so-called because, with no ad revenue, the uploader doesn’t make any money.

They complain that Google’s YouTube refuses to explain why it stops running advertisements alongside some videos. YouTube CEO Susan Wojcicki wrote in a blogpost the move was in response to complaints by brands that their ads were being shown alongside “inappropriate” content. But creators aren’t explicitly told what rules they breached when a clip becomes ineligible for ads.

Some saw their income fall by 80% after a 2017 change to the rules. Even the prominent YouTuber Casey Neistat, who now has 11 million subscribers, found an apparently uncontroversial Indonesian travelogue was de-monetized. Others have puzzled over the rationale. British YouTuber Jack Massey Welsh, who posts his wacky antics on the channel JackSucksAtLife, revealed last year that clips of himself drinking milk and of someone swearing while playing Minecraft were de-monetized. He said YouTube never explained why.

Regardless of whose side you’re on, the entry of a heavyweight labor union into this battle should be seen as a healthy test of its ability to rebalance the power dynamic between Google and the millions of people whose income derives from uploading videos to the site. The fight reflects how digital platforms have reconstructed the seemingly straightforward relationship between employer and employee.

IG Metall wants YouTube to be more transparent with its community of creators. The German union is inviting YouTubers to become members and is running a campaign called FairTube to press for better terms. The initiative is in its early days and IG Metall won’t disclose how many YouTubers it’s signed up. Even so, it’s given Google a deadline of August 23 to come to the negotiating table. If it refuses, IG Metall plans to use its deep pockets and army of lawyers to pursue legal options.

It’s a remarkable precedent. While labor unions have already represented others who aren’t salaried employees of tech firms – ridehailing drivers and other gig economy participants, for instance – IG Metall is trying to organize a disparate group which provides a less tangible service.

Meet Monopsony, Creature of a Puzzling Labor Market

It’s a far more challenging battle than for, say, factory workers. Online platforms by their very nature tend to pit diverse groups of people, sometimes thousands of miles apart, against each other to offer the best service at the lowest possible price. Collective bargaining, in this context, doesn’t really work.

A strike in the traditional sense would achieve little. Even in the extreme unlikelihood that every YouTuber in Germany boycotts the platform and stops uploading videos, it would have a limited impact on the site’s profitability. While a localized strike by Uber drivers can cripple the ridehailing service for its duration, YouTube has unparalleled cross-border scale – 450 hours of video are uploaded every minute – and an almost bottomless library of existing content.

So what exactly can IG Metall do? A lawsuit is the most likely next step. The union claims that decisions made to de-monetize a video with no explanation contravene the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. One strand of the rules, introduced last year, gives people the right to know whether their personal data is being processed, for what purpose, and to request a copy of it all. The union argues that algorithms deciding to stop ads being attached to a clip generate such data. It’s a smart play. With the deep pockets afforded by its huge membership, IG Metall is able to contest issues where an individual would struggle.

Notably, the union is trying to use the same tool of its members’ atomization – the online platform – to organize them. Even before it joined forces with the YouTubers Union Facebook group, IG Metall had launched an initiative called FairCrowd, a website where gig economy workers provide feedback on the apps they work for. It’s not that far from its home turf: IG Metall already represents employees at tech companies like SAP SE.

Unions are ultimately fearful that disruption from digital platforms could unravel much of the progress they’ve made in improving labor conditions over the past 150 years. The employee-employer contract is, at its core, fairly basic: the employee receives a steady income and other insurance and agrees to subordinate him- or herself to the employer (within reason) in return. Trade unions have helped establish the limits of what is reasonable.

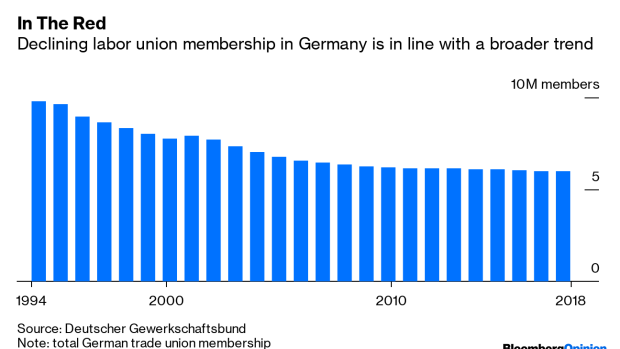

Conversely, an independent contractor enjoys greater freedom and isn’t subordinated to a single employer, but can’t bank on getting a guaranteed salary.Digital platforms often now impose strictures which can give them an employer-like power over people who are dependent on them for their livelihood, but without the associated benefits such as a steady income. Meanwhile unions, whose membership numbers are slowly declining, are trying to establish their role in that relationship. IG Metall’s FairTube is an early sally.

To contact the author of this story: Alex Webb at awebb25@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stephanie Baker at stebaker@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe's technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.