Mar 19, 2020

The Time for 50-Year Treasuries May Have Finally Come

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In many ways, it seemed almost inevitable that at some point during the U.S. government’s deliberations about providing fiscal stimulus, the topic of ultra-long Treasury bonds would come up.

Bloomberg News’s Saleha Mohsin and Jennifer Jacobs reported Thursday that among the many options to finance a $1.3 trillion fiscal stimulus plan, President Donald Trump’s advisers are considering 50- and 25-year bonds. White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow reportedly likes the idea, and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin has warmed to it after being initially skeptical.

Mnuchin has reason for pause. The prospect of issuing 50-year or even 100-year Treasuries has defined his tenure in the eyes of the world’s biggest bond market since even before the president was sworn into office. In December 2016, traders, strategists and even duration-starved bond investors I spoke with quickly dismissed the idea of ultra-long bonds. This would happen again and again to Mnuchin in the coming years, with bond dealers on the influential Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee expressing unwavering skepticism that adding a point further out on the yield curve could be done in a regular and predictable manner.

This is why I said in January that Mnuchin made the right call by playing it safe and deciding to issue 20-year bonds instead. It simply isn’t worth shaking things up just for the sake of it when it comes to financing the U.S. government.

That was before the coronavirus brought the world’s largest economy to its knees, however. As government officials contemplate the best path forward, 50-year Treasuries deserve a fresh round of consideration.

The bond dealers’ argument likely still holds that the Treasury Department would struggle to issue ultra-long bonds in a “regular and predictable” way that has long been a pillar of how it manages the country’s debt. It would take time for a sufficient amount of 50-year debt to trickle into the secondary markets to establish firm trading levels — if the investors interested in the bonds would even want to trade it at all. At least initially, the debt would probably yield more than it should in theory against 30-year Treasuries. That could be a problem if the Trump administration is truly focused on figuring out the best way to borrow with the lowest costs to taxpayers, as the Bloomberg News reporting suggested.

If the government wanted to get truly creative during this tumultuous period, it might reconsider a plan like the one floated by U.S. Representative John Yarmuth of Kentucky in December 2018. I wrote about his proposal to have the government issue as much as $300 billion of 40-year bonds only to public and private pension funds, with the proceeds used to provide capital for a U.S. infrastructure bank. The interest rate would be 2 percentage points more than 30-year bonds and pensions would have to hold the debt for at least 10 years.

The same sort of framework could apply here. If the biggest roadblock to issuing 50-year Treasuries is that they can’t be auctioned in the same way as the other maturities, what if Mnuchin just skipped over that altogether? The U.S. could conceivably announce a handful of ultra-long bond deals as a part of its overall pandemic response and state upfront that it will go back to only borrowing for up to 30 years once the worst of the economic damage is behind the country.

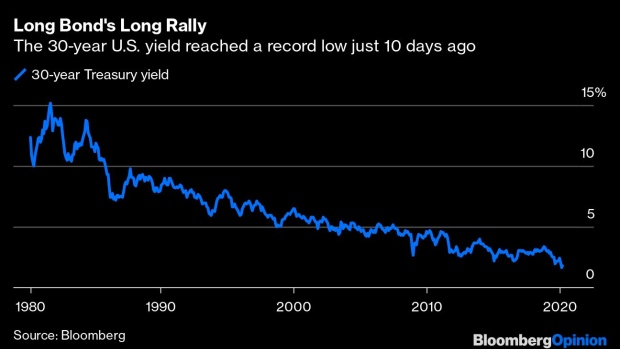

Yarmuth’s idea of fixing interest rates and selling only to pension funds still has merit, especially considering the inevitable hit to state and local government budgets from the near-collapse in economic activity. Public retirement funds still have lofty return assumptions that don’t reflect the reality of near-record low Treasury yields. Without question, the sharp declines in equities and other risk assets are going to take their toll on the funded status of public pensions. Given the expected reduction in tax revenue, few if any states or localities will have the money to “buy low” and contribute more to their plans. Rather, as evidenced by the last recession, they’ll have to shortchange them.

When Yarmuth’s idea first came to light, I questioned whether it was the federal government’s place to close markets to certain investors and pick winners, regardless of how much some pension funds may need the boost. That seems quaint in the coronavirus era. There’s now talk of bailouts for the biggest airlines as well as Boeing Co. and General Electric Co. Kudlow said Wednesday that the administration might consider asking for an equity stake in companies that want coronavirus aid from taxpayers. Governments and central banks around the world are throwing the kitchen sink at this economic slowdown, regardless of the optics of meddling.

For that reason alone, the 50-year Treasury bond’s time may have finally arrived. The European Central Bank just unveiled what it calls the “Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme,” an $820 billion bazooka. It’s not hard to envision the Treasury announcing sales of “Pandemic Emergency Bonds” with ultra-long maturities, marketed with an appeal to patriotism akin to war bonds. That would help create further distance from the rest of the $17 trillion Treasury market, which abides by the regular-and-predictable mantra.

Or Mnuchin could take the easier path once again and just methodically ramp up the auction sizes of current Treasury maturities. But if he wants to see his pet project of more than three years come to life, this looks like an opening to make it happen.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.