May 22, 2019

The Trade War's Grip on Currency Markets Tightens

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Trade tensions between the U.S. and China are starting to pull foreign-exchange markets into the arena. Yet far from embracing their currencies as a weapon, many countries are being forced to take a defensive posture against the almighty dollar.

Central banks seem more intent on keeping their currencies steady and stopping money from escaping rather than engaging in devaluations to boost their competitiveness in trade. Officials in China, South Korea and Indonesia on Wednesday were among those taking steps to buoy their currencies as the prospect of more rapid depreciation raised the specter of capital outflows.

In the meantime, the standoff between the world’s two largest economies is pushing uneasy investors into the greenback and U.S. policy makers may face problems if the stronger dollar -- which is currently near its highs for the year -- is seen as crimping their efforts to promote higher inflation.

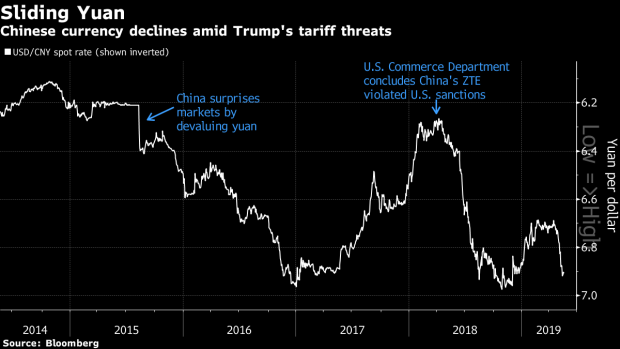

The forces roiling currencies are magnifying the focus on China and how it will handle a cheapening yuan. Options traders are pricing in around a 35% chance that the renminbi will by year-end weaken past 7 per dollar -- a level unseen since the financial crisis. At the end of March, the probability was just 15%. That kind of depreciation would threaten to heighten tensions with the U.S. and potentially drive emerging-market currencies broadly lower.

“The outcome of the trade war should be to bid the dollar, drain emerging-market foreign reserves,” and push investors into Treasuries, said Sebastien Galy, senior macro strategist at Nordea Investment Funds. “At the end of the day, there is only one winner, the dollar.”

Markets have been buffeted by uncertainty as the trade impasse shows no sign of abating. Almost all emerging-market currencies have weakened this month against the greenback. The onshore yuan is among the biggest losers, falling 2.5% in May to around 6.9063 per dollar on Wednesday, close to its cheapest level since 2018. South Korea’s won slid this week to its weakest in more than two years, while the Indonesian rupiah has set a new 2019 low.

While a falling currency could boost exports, central banks are signaling their goal now is to stem investor flight.

“Korea is exposed in the tech space and Indonesia is usually one of the currencies that hurts the most in dollar strengthening,” said Lisa Synning, a money manager in Stockholm, whose Handelsbanken Tillvaxtmarknad emerging-markets equity fund has trounced 98% of peers this year. “Of course, they worry and want to take some action.”

Authorities in Seoul called a snap meeting to discuss what they see as distortions in the currency market, while Bank Indonesia -- which has been intervening in markets recently -- said it would coordinate with banks and other institutions to guard rupiah stability.

The People’s Bank of China on Wednesday set its currency fixing at a level stronger-than-expected for a third straight day. The strengthened reference rate, which restricts the moves of the onshore yuan by 2% on either side, helped to halt a record slide in the currency’s value against a basket of peers.

Investors are looking to next month’s meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and U.S. President Donald Trump at the Group-of-20 gathering in Osaka as a potential turning point. Should the two leaders fail to agree and the yuan slides, analysts will be watching to see how China responds.

A weakening foreign-exchange rate “is the natural means of offsetting tariffs,” George Saravelos, strategist at Deutsche Bank AG, said in a note May 17.

The Trump administration earlier this month increased tariffs on $200 billion worth of Chinese goods to 25% and has threatened to also levy the impost on everything else imported into the U.S. from the world’s most populous nation. If the White House decided to apply a fresh 25% tariff on the remaining $300 billion of imports not currently affected, the yuan would need to depreciate to around 8.12 per dollar to offset it, according to calculations published by Bank of America strategists on May 17.

Recent currency weakness spooked traders who consider 7 yuan per dollar to be a line in the sand. A shock devaluation in August 2015 helped drive a decline of nearly $2 trillion in value from stocks in the 31 largest emerging markets that month. And 19 of 24 developing-nation currencies in a basket tracked by Bloomberg slid that month, with the Malaysian ringgit, Colombian peso and Brazilian real leading declines.

Still, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. expects any move by the yuan through 7 to be “gradual and orderly,” strategists led by Zach Pandl wrote in a report last Friday. That’s because Chinese policy makers have signaled their desire for currency stability and maintaining that requires a minimal amount of official reserves.

Goldman said wagers on a stronger greenback are better expressed through dollar-yuan call spreads, which bet on the currency pair trading within a specific range, or through other regional proxies such as the Taiwanese dollar.

“The yuan’s vulnerability to market sentiment has increased post-trade war, ” said Lale Akoner, a strategist at Bank of New York Mellon. “We expect to see a continuation of this, so central banks are defending their currencies.”

--With assistance from Enda Curran and Hooyeon Kim.

To contact the reporters on this story: Susanne Barton in New York at swalker33@bloomberg.net;Ben Bartenstein in New York at bbartenstei3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, ;Julia Leite at jleite3@bloomberg.net, Mark Tannenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.