Jan 29, 2019

The Treasury’s Secretive Bond Whisperers Are More Crucial Than Ever

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Every three months, they come to the nation’s capital to gather at the iconic Hay-Adams hotel, just steps from the White House.

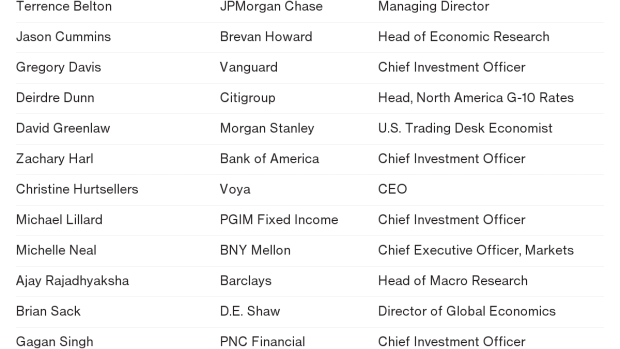

Here, 12 men and five women, representing Wall Street’s most influential dealers and debt investors -- names like JPMorgan Chase, BlackRock and Citadel -- meet with Treasury Department officials behind closed doors with one important purpose: to tell them how to manage America’s finances.

Created shortly after World War II to help the U.S. government oversee its burgeoning debt burden, this group of bond-market whisperers has, at times, been criticized for its secretive nature and potential conflicts. But the advice of the 17-member Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, commonly referred to as TBAC, has arguably never been more important.

The Trump administration’s tax cuts have economists seeing trillion-dollar deficits for years to come. Financing those shortfalls will require ever-growing amounts of borrowing, and any missteps in how the U.S. manages that burden could potentially cost hundreds of billions in extra interest payments.

“Treasury debt management is a big issue and it’s going to become much bigger now that fiscal deficits are going to be so large,” said Darrell Duffie, a finance professor at Stanford University. “TBAC contributes importantly in providing advice from large financial firms. ”

TBAC members meet with Treasury officials on Tuesday at the Hay-Adams (an oft-featured spot on Netflix’s political drama “House of Cards”), usually at around 9 a.m. Because of worries about leaks of sensitive, market-moving information, mobile phones are a no-no and devices are collected beforehand.

During the day-long meeting, members provide Treasury officials advice on financing options for the current quarter and guidance on longer-term debt-management policies. The committee’s chair, currently Goldman Sachs Treasurer Elizabeth Hammack, then presents its report -- laying out what’s generally viewed as Wall Street’s position on those matters -- to Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. (People familiar with the discussions say Mnuchin has encouraged more freewheeling conversations for these types of meetings, and once asked whether they wanted the Federal Reserve to tighten monetary policy by raising rates or through faster cuts in its debt holdings.)

The next day, the Treasury releases its quarterly financing plan, with details of how it will fund the government’s borrowing needs at its debt auctions, along with a summary of the minutes from its meeting with TBAC.

Less well known is also the fact that TBAC meets regularly in Washington with Fed board members in an unofficial advisory capacity, generally around the same time as the Treasury’s refunding, as long as it doesn’t coincide with the Fed’s policy meetings. The final meeting last year took place on Sept. 13, according to Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s public calendar. The meetings are strictly for board members gather information from TBAC members, rather than the other way around.

The Board meets with many outside groups and values the opportunity to hear a wide range of views on financial conditions and the economy, a Fed spokesman said.

Current members of TBAC declined to speak publicly about their discussions, when asked by Bloomberg. The Treasury also declined to comment.

Treasury officials, of course, take pains to stress that they don’t just rubber-stamp TBAC’s recommendations. They must minimize borrowing costs while maintaining regular and predictable debt auctions to ensure that Treasuries remain a liquid, global benchmark.

“TBAC’s recommendations are just that, recommendations,” Brian Smith, Treasury’s deputy assistant secretary for federal finance, said during a December New York Fed conference. “Treasury remains the sole decision maker regarding issuance decisions.”

Nevertheless, TBAC’s clout is undeniable. While Mnuchin and other Trump administration officials repeatedly and publicly talked up in early 2017 the possibility of issuing ultra-long Treasuries due in 50 or even 100 years, they pretty much dropped the subject after TBAC’s skepticism and its own discussions with investors. Instead, the committee recommended that the government skew debt sales in favor of maturities of five years or less.

How the U.S. government intends to fund itself has become a more pressing question as the deficit swells. Net issuance of Treasuries will jump to $1.4 trillion this year from $1.34 trillion in 2018, according to Deutsche Bank. That’s more than twice the amount sold in 2017. While yields on Treasuries remain relatively contained, with the 10-year note hovering at 2.74 percent, any letup in demand could easily swell funding costs. Last fiscal year alone, interest payments on U.S. debt obligations reached a record $523 billion.

Not everyone is a fan of TBAC’s clubbiness or its decisions.

Jim Bianco, president of Bianco Research, says TBAC should include people from outside Wall Street. While the Treasury the final say on all members, picking them falls primarily on the chair. Members themselves gather the day before the meeting for a private dinner to discuss the agenda and their views.

Bianco also says their guidance against ultra-long bonds caused the Treasury to miss an opportunity, which many other countries took, to lock in historically low long-term interest rates. (In September 2017, Austria sold 100-year bonds to yield 2.112 percent, less than 10-year Treasuries at the time.)

Then, there are the potential conflicts of interest. While rare, there have been instances when TBAC members have been investigated for allegedly trading on insider information. One former Treasury official, who asked not to be identified, wanted to end TBAC, saying the risks of leaks outweighed the potential advantages.

Cerberus Capital Management’s Matt Zames, who was a member for eight years, defends the committee. The former TBAC chair says the committee is like any other private-sector advisory board tasked with providing the government with expert advice. What sets it apart, he says, is that TBAC has made a real difference.

“What makes TBAC special is that its work over the years has led to real, tangible value for U.S. taxpayers,” Zames said. “Chairing TBAC was one of the most meaningful things I’ve done in my career.”

--With assistance from Chris Middleton, Kristy Scheuble, Saleha Mohsin and Rich Miller.

To contact the reporter on this story: Liz Capo McCormick in New York at emccormick7@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Purvis at bpurvis@bloomberg.net, Michael Tsang, Mark Tannenbaum

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.