Feb 20, 2021

The Two Hours That Nearly Destroyed Texas’s Electric Grid

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- The control room of the Texas electric grid is dominated by a Cineplex-sized screen along one wall and last Sunday night, as outdoor temperatures plunged to arctic levels around the low-slung building 30 miles from Austin, all eyes were on it. The news wasn’t good.

Electric demand for heat across the state was soaring, as expected, but green dots on the corner state map started flipping to red. Each was a regional power generator and they were spontaneously shutting down — three coal plants followed quickly by a gas plant in Corpus Christi.

Then another metric began to flash: frequency, a measure of electricity flow on the grid. The 60 hertz needed for stability fell to 59.93.

Bill Magness, chief executive of the grid operator, was watching intently and understood instantly what was at stake. Below 59 and the state’s electrical system would face cascading blackouts that would take weeks or months to restore. In India in 2012, 700 million people were plunged into darkness in such a moment.

Texas was “seconds and minutes” from such a catastrophe, Magness recalled. It shouldn’t have been happening. After the winter blackouts of 2011, plants should have protected themselves against such low temperatures. The basis of the Texas system is the market — demand soars, you make money. Demand was soaring last Sunday but the plants were shutting down.

If insufficient power came in, the grid wouldn’t be able to support the energy demand from customers and the other power plants that supply them, causing a cycle of dysfunction. So over the following hours, Magness ordered the largest forced power outage in U.S. history.

More than 2,000 miles away in San Juan, Puerto Rico, power trader Adam Sinn had been sitting at his computer watching the frequency chart plummet in real time. He knew the dip would be enough to start forcing power plants offline, potentially causing more widespread blackouts. It was an unprecedented situation but, from his perspective, entirely avoidable.

In fact, it was a crisis years in the making. Texas’s power grid is famously independent — and insular. Its self-contained grid is powered almost entirely in-state with limited import ability, thereby allowing the system to avoid federal oversight. It’s also an energy-only market, meaning the grid relies on price signals from extreme power prices to spur investments in new power plants, batteries and other supplies.

There is no way to contract power supply to meet the highest demand periods, something known as a capacity market on other grids. There are no mandates or penalties compelling generators to make supply available when it’s needed, or to cold-proof their equipment for storms like the one that slammed Texas last weekend.

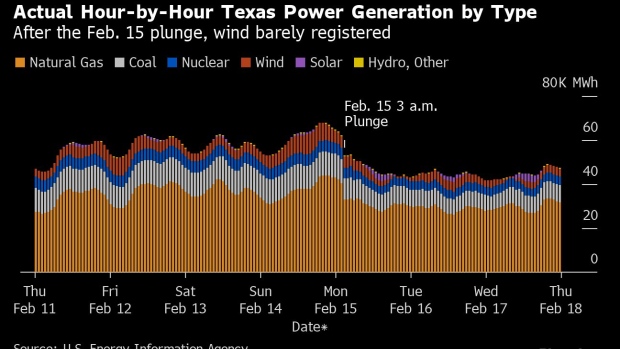

So, as the cold began shutting in natural gas supplies, freezing instruments at power plants and icing over wind turbines, there wasn’t enough back-up generation available to meet demand. As many as 5 million homes and businesses were abruptly thrust into frigid darkness for nearly four straight days as the crisis continued, ensnaring more than a dozen other states as far as away as California and roiling commodity markets across the globe.

Now, as the snow across Texas melts and the lights come back on, answers remain hard to come by. What’s clear is that no one — neither the power plants that failed to cold-proof their equipment nor the grid operator charged with safeguarding the electric system — was prepared for such an extreme weather event. What happened in those two hours highlights just how vulnerable even the most sophisticated energy systems are to the vagaries of climate change, and how close it all came to crashing down.

The warning signs started well before the cold set in. Nearly a week before the blackouts began, the operator of a wind farm in Texas alerted the grid manager, known as Ercot, the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, that ice from the impending storm could force it offline, an early signal that capacity on the system would likely be compromised.

On Thursday, a natural gas trader trying to secure supplies for his company’s power plants for the holiday weekend was surprised to see prices surging. The reason? There were concerns that gas production in West Texas was at risk of freezing off, which would crimp supplies for power generation. And Sinn, the owner of Aspire Commodities, noticed from his computer in San Juan that day-ahead power prices on Texas’s grid were climbing, a sign that the market was anticipating scarcity.

By Saturday, a considerable amount of capacity was already offline, some of it for routine maintenance and some of it due to weather. This is because in Texas peak demand is associated with summer heat so many plants do routine maintenance in winter.

Wind was the first to go, as dense fog settled over turbine fleets, freezing on contact. The slow build-up of moisture over several days caused some of the blades to ice over, while connection lines began to droop under the weight of the ice until power production from some wind farms completely ceased. But because the resource makes up a minor share of Texas’s wintertime power mix, grid operators didn’t view it as a big problem. Then gas generation began declining. That was inconvenient, but not unmanageable. There was still plenty of supply on the system.

On Sunday, the mood in the control room grew tense. As the cold deepened, demand climbed sharply, hitting and then exceeding the state’s all-time winter peak. But the lights stayed on. Magness and his director of system operations, Dan Woodfin, watched the monitors from an adjoining room, satisfied that they had made it through the worst of the crisis.

“We thought maybe we are OK for the rest of the night,” Magness said.

They weren’t.

At 9 p.m., output from the Sandy Creek coal plant near Waco plunged to one-third of its capacity. On the monitor overlooking the control room, the green dots turned red.

Across the state, power plant owners started seeing instruments on their lines freezing and causing their plants to go down. In some cases, well shut-ins in West Texas caused gas supplies to dip, reducing pressure at gas plants and forcing them offline. At that point, virtually all of the generation falling off the grid came from coal or gas plants.

“Contrary to some early hot takes, gas and coal were actually the biggest culprits in the crisis,” said Eric Fell, director of North America gas at Wood MacKenzie.

Back in Taylor, the town northeast of Austin, where Ercot is based, orange and red emergency displays began flashing on the giant flat-screens that lined the operators’ workstations.

“It happened very fast, there were several that went off in a row,” Magness said.

In the span of 30 minutes, 2.6 gigawatts of capacity had disappeared from Texas’s power grid, enough to power half a million homes.

“The key operators realized, this has got to stop. This isn’t allowed to happen,” said Magness.

By that point, the temperature outside had fallen to 5 degrees Fahrenheit. Across the state, streets were icing over and snowbanks piling up. Demand kept climbing. And plants kept falling offline.

No one in the room had anticipated this. And it was about to get worse.

The generation outages were causing frequency to fall — as much as 0.5 hertz in a half-hour. “Then we started to see lots of generation come off,” Magness said.

To stem the plunge, operators would have to start “shedding load.” All at once, control room staff began calling transmission operators across the state, ordering them to start cutting power to their customers.

“As we shed load and the frequency continued to decline, we ordered another block of load shed and the frequency declined further, and we ordered another block of load shed,” said Woodfin, who slept in his office through the crisis.

Operators removed 10 gigawatts of demand from 1:30 a.m. until 2:30 a.m., essentially cutting power to 2 million homes in one fell swoop.

The utility that services San Antonio, CPS Energy, was one of those that got an order to cut power.

“We excluded anything critical, any circuit that had a hospital or police,” CPS chief executive Paula Gold-Williams said Friday. “We kept the airport up.”

Alton McCarver’s apartment in Austin was one of the homes that lost power. The IT worker woke shivering at 2:30 a.m., an hour after the blackouts began, and tried turning up the thermostat. “Even my dog, he was shaking in the house because he was so cold,” he said.

McCarver wanted to take his wife and 9-year-old daughter to shelter with a friend who still had power, but the steep hills around their home were coated in ice and he didn’t think they could make the drive safely. “You’re hungry, you’re frustrated, you’re definitely cold,” he said. “I was mostly worried about my family.”

The power cuts worked — at least in so far as Ercot managed to keep demand below rapidly falling supply.

But the grid operator shed load so rapidly that some generators and market watchers have wondered whether they exacerbated the problem.

What’s more, frequency continued to fluctuate through the early hours of the morning, potentially causing even more power plants to trip offline, according to Ercot market participants. Ercot, however, maintains that the frequency stayed above the level at which plants would trip.

And as blackouts spread across the state, power was cut not only to homes and businesses but to the compressor stations that power natural gas pipelines — further cutting off the flow of supplies to power plants.

Power supplies became so scarce that what were supposed to be “rolling” blackouts ended up lasting for days at a time, leaving millions of Texans without lights, heat and, eventually without water. Even the Ercot control center lost water, and had to bring in portable toilets for its staff.

“It’s just catastrophic,” said Tony Clark, a former commissioner with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and a senior adviser at law firm Wilkinson Barker Knauer LLP.

By Friday, when Ercot declared that the emergency had ended, 14.4 million still lacked reliable access to public water supplies, and the crisis had already cost the state $50 billion in damages, according to Accuweather. The cost of power on Monday alone was $10 billion, according to estimates from Wood Mackenzie.

But at least the lights were coming back on. In the afternoon, shell-shocked people trickled out of their homes to soak up the sun. “It feels crazy standing outside in the 40 degree sunlight,” said Cassie Moore, a 35-year-old writer and educator, who offered up her shower and washing machine to her boss and friends who were still without power or water. “In this same spot a few days ago I was worried that my dogs might freeze to death.”

—With Javier Blas

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.