(Bloomberg) -- With new restrictions and Brexit threatening to push the U.K. back into recession, the economy is probably more than a year away from recouping the staggering losses inflicted by the coronavirus.In broad terms, no sector has escaped the carnage. Economic output is still almost 10% below pre-pandemic levels, 800,000 fewer employees are on payrolls and the government is borrowing on a scale not seen in peacetime in a bid to avert mass unemployment and keep struggling businesses afloat.Beneath the surface, however, sharply diverging fortunes can be perceived. The housing market is enjoying its best run for years, buoyed by government stimulus and pent-up demand. Retail sales are at an all-time high. Job cuts, meanwhile, have fallen hardest on young people seeking a foothold in the labor market.On day 12 of a new lockdown in England to tackle a resurgent Covid-19 outbreak, the following charts provide an overview of the Group of Seven’s hardest-hit economy, eight months after the crisis struck.

The Bank of England had no idea of what lay in store when it delivered its normal forecasting round in January. Brexit presented the biggest threat, policy makers said, as they predicted growth of around 1.5% a year and unemployment remaining below 4%.

As of the third quarter, the economy was over 10% smaller than predicted back then, and officials now don’t expect a return to pre-crisis levels until early 2022 -- even if Britain and the European Union clinch a Brexit trade deal. Unemployment stood at 4.8%, the most in four years, after an unprecedented 314,000 redundancies.

On Nov. 5, Chancellor Rishi Sunak announced that furloughed workers will get 80% wage support through March. That may help limit the peak in joblessness to around 7.5%, according to Dan Hanson of Bloomberg Economics.

If any businesses are having a good pandemic, they are couriers, estate agents and some retailers, according to Office for National Statistics data last week.

The real-estate market reopened over the summer, releasing a wave of demand that was further fueled when Sunak announced a temporary tax cut for property buyers. Spending on gardens and house improvements has sustained Britons forced to spend more time at home. The strength of demand for postal services is unsurprising given the shift toward online purchases.

Their fortunes stand in stark contrast to hospitality, leisure and the performing arts. Hardest hit are travel agents, tour operators and air transport services, where output has plunged by over 80% since the end of 2019. Divergences are narrower in manufacturing, which has experienced fewer disruptions to day-to-day operations.

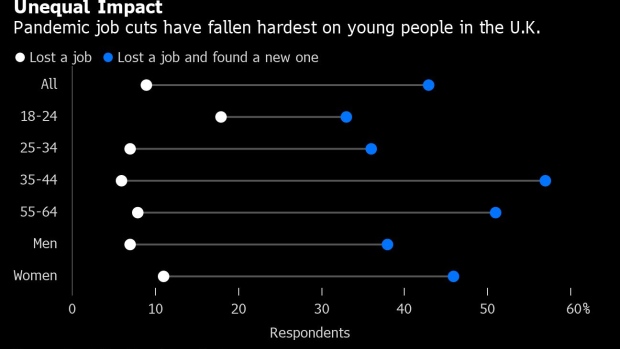

Just as they did in the global financial crisis, young people are bearing the brunt of the pandemic.

About a fifth of 18 to 24-year-olds who were furloughed have now lost their jobs, and only a third of those let go have been able to find new work, according to the Resolution Foundation. Youth unemployment jumped to 13.6% in the third quarter, almost triple the national average.

The figures pile pressure on Prime Minister Boris Johnson to do more to create jobs and retrain unemployed workers.

Even before the crisis, young people were struggling with unaffordable housing, job insecurity and years of wage stagnation. Now they potentially face further damage to their long-term prospects through the effects of scarring on earnings and employment.

The pandemic has wrought havoc with the public finances, pushing debt above 100% of GDP for the first time since Harold Macmillan was prime minister in the early 1960s.

The budget deficit, which was forecast to be just 55 billion pounds ($72 billion) in the current fiscal year, is now on course to exceed 400 billion pounds. As a share of the economy, that’s double the level reached after the financial crisis.

The scale of the damage will be laid bare on Nov. 25, when the Office for Budget Responsibility is due to publish new forecasts. Tax increases in the coming years appear inevitable but there is no immediate pressure on Sunak, with the International Monetary Fund arguing further stimulus may even be necessary.

Financial markets are sanguine too. With the Bank of England mopping up every pound of borrowed money through its bond-buying program, the cost of taking on debt has never been cheaper.

The challenge facing Sunak is vividly highlighted by the fact that Britain’s recovery trails far behind the world’s major industrialized nations, despite a record rebound in the third quarter.

Output was still 9.7% below end-2019 levels, leaving Britain closer to euro-area laggard Spain than its Group of Seven peers, where the average shortfall was little more than 4%. On Monday, Japan reported stronger-than-forecast 5% growth for the quarter, or an annualized 21.4%.

U.K. business investment has stagnated since the 2016 Brexit referendum, and in the third quarter it recovered less than 25% of what it lost in the previous three months. The reticence of companies to spend reflects both the pandemic and concerns about Britain’s imminent exit from the EU single market -- potentially with no trade deal.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.