Jan 15, 2020

There’s Something Fishy About China's U.S. Food Imports

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Every big deal in China should be celebrated with a banquet.

That’s certainly the expectation on the U.S. side after the signing of a phase-one trade agreement in Washington on Wednesday. Beijing has promised to increase its imports from the U.S. by $100 billion a year over the next two years.

America’s ample exports of beef, pork and chicken seem perfectly positioned to take advantage: Chinese pork prices have nearly doubled over the past year because of Asian swine fever, leaving the country severely short of its favorite meat.

Americans who want to profit from the change in China’s appetite for imported protein should probably consider thinking about it from the perspective of Asian diets, though. Some of the foodstuffs that will benefit most from any growth in U.S. exports aren't key items on the menu at McDonald’s.

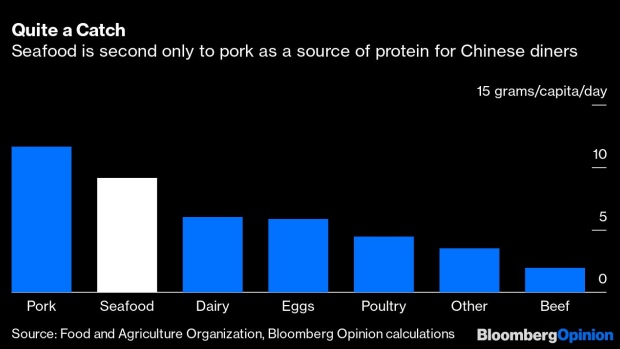

Take seafood. Fish is second only to pork in the appetites of Chinese diners. Of the 43 grams of protein that the country consumes per person, per day, pig meat accounts for 12 grams and fish for 6.5 grams, ahead of 6 grams for dairy, 4.5 grams for poultry, and less than 2 grams for beef. Add in shellfish, seaweed and other delicacies, and seafood as a whole amounts to 9.15 grams a day.

Look down the categories of animal product that China imported from the U.S. in 2018, and it’s led by foods that are thought about in the context of trade diplomacy far less than the usual farm produce: Frozen whole fish, crustaceans, and mollusks are all more important than pork, for instance.

As anyone who’s eaten a Chinese meal would know, the country has a huge appetite for seafood, particularly in the coastal provinces where incomes are highest and imported food most affordable. There’s a problem, though: The country’s huge domestic aquaculture industry hit capacity limits several years ago, and demand for live-caught seafood is actually falling, in part due to concerns around the collapse of marine food chains from overfishing.

That makes imports from other countries an attractive alternative. Purchases of seafood from overseas increased 14% in the first 11 months of 2018 to 3.06 million tons, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and jumped 45% by value to $10.65 billion. America sits between Russia and Canada as China’s biggest supplier of imported seafood, and some American delicacies, such as crayfish and Maine lobster, are heavily in vogue despite hefty tariffs.

Most of the supply chains to facilitate this trade are already well-established. Indeed, the primary barrier to increasing U.S. seafood exports to China is that the country already accounts for a significant slice of the trade — around 30% to 40% for the major categories of frozen fish, crustaceans and mollusks. In the case of pork, chicken, and beef, food-safety and quarantine restrictions mean that China accounts for a far smaller proportion of U.S. exports, on the scale of a percentage point or less. That offers substantial upside, although much of it will depend on American slaughterhouses working harder than they have in the past to establish additive-free supply chains that meet China’s food standards.

Innards seem another attractive path to Chinese bellies. Modern Americans strongly favor lean cuts on their plates, but China’s appetite for tripe, liver and kidneys means offal imports from the U.S. are worth about six times as much as the beef trade at present. A container holding 23.94 metric tons of American chicken feet that cleared Chinese customs Tuesday was the first major import of U.S. poultry to China after a five-year ban put down to avian flu, the official Securities Times reported this week. Brazilian pig offal was approved for import for the first time in November, amid the decline in domestic supply due to African swine fever.

At a time when as much as 40% of the U.S. food supply is wasted, there’s a pleasing symmetry to a trade deal that allows commerce between China and America to heal by letting the two countries divide their meat into the bits they respectively like best. If three years of trade tensions are to be settled in a spirit of comity, there are few better ways to start than breaking bread together.

To contact the author of this story: David Fickling at dfickling@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.