Dec 5, 2019

This $1.2 Trillion China Bond Market Is Studded With ‘Fakes’

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Markets) -- One corner of China’s bond market is offering yields that seem too good to be true. And, indeed, it’s permeated with “fakes.”

Since 2009, off-balance-sheet shell companies set up by Chinese municipalities have been selling debt to fund infrastructure projects. Called local government financing vehicles, or LGFVs, they were initially intended to supplement the stimulus Beijing launched to rescue China’s economy after the 2008 credit crisis. In the past 10 years these vehicles have amassed a huge pile of debt: 33 trillion yuan ($4.7 trillion), according to S&P Global Ratings. Of that, about 8.3 trillion yuan, or $1.2 trillion, is in bonds.

Yields on these securities tend to be attractive, especially in a world where $12 trillion of bonds have negative interest rates. Because they’re not part of the municipalities’ budgets, LGFVs typically offer higher coupons. The average coupon of outstanding LGFV notes was 3.9% in October, while the average for yuan-denominated corporate bonds was 3.0%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Of China’s 3.6 trillion yuan of bonds that paid more than 6% at the end of September, about 45% was issued by LGFVs.

Beijing started allowing some state-owned enterprises to go bust in 2015, yet not a single LGFV bond has failed to satisfy its obligations, despite scant cash flow and mounting debt. There have been some close calls, though. In August 2018 an organization attached to the army in China’s western Uighur region missed a deadline to repay its bond by two days. Such “technical defaults”—slightly delayed wire transfers—have become more common since.

Still, LGFV bonds are now seen as one of the most desirable assets in China. Strong demand from foreign fund managers has pushed LGFV dollar-bond sales to an all-time high this year. Along with their attractive yields, the bonds’ appeal stems from investors’ view that they’re low-risk. The reasoning here, while a little convoluted, goes something like this: Local governments’ fiscal revenue is growing at the slowest pace in at least a decade, thanks to corporate tax cuts and an economic slowdown. Yet spending on infrastructure is still needed in many parts of China, giving Beijing an incentive to keep this financing channel open—which means preventing LGFV defaults.

But there’s a major problem: Many LGFVs are no longer sticking to their construction mandates. Investors call them fakes.

As early as 2010, Beijing asked municipalities to refrain from borrowing funds for construction projects that would rely on repayment from the central government. As a result, many LGFVs pushed into new businesses to generate cash. Some have gone rogue, ditching underappreciated public services altogether. One example is Changde Economic Construction Investment Group Co., whose original focus was funding urban construction projects in Changde city in central Hunan province. Now it’s set up businesses in five sectors, including tourism and financial services. In local parlance, these types of LGFVs that don’t finance infrastructure or social welfare projects are referred to as fakes.

Qin Han, chief fixed-income analyst at Guotai Junan Securities Co., says LGFVs that engage in funding railway, superhighway, or shantytown renovation should be safer investment opportunities because they’re more likely to get government support. “It is because funding borrowed for such projects is likely to be supported by top regulators’ debt workout policies,” Qin says, “as well as money granted by financial institutions to ease liquidity crunch, if there is any.” As for “fake” LGFVs, Beijing will let a few go bust sooner or later.

Nasty surprises can emerge. Qinghai Provincial Investment Group, for example, was long considered an LGFV by at least some bond investors. When the aluminum maker made late coupon payments in February and again in August, doubt surfaced. S&P Global Ratings said in a March report that Qinghai Provincial should be viewed as a state-owned enterprise rather than an LGFV because it doesn’t carry out significant public welfare activities. “The company’s weak standalone credit profile is primarily due to its high production costs, weak competitive position, sector cyclicality, and high financial leverage,” the rating agency said.

In times of distress, demand for LGFV bonds can freeze suddenly. Case in point: In June, after its first bank seizure in a decade, China experienced a liquidity squeeze in the opaque repurchase market, where financial institutions offer bonds as collateral for short-term cash loans. Banks rejected many high-yield issues as collateral, including LGFV bonds, because they didn’t know their real worth. To drum up demand, issuers of as much as 8% of China’s corporate bonds had indirectly purchased a portion of their own bonds. Roughly half of new LGFV bond issues were privately placed, according to Bloomberg data, making it hard to know the ultimate owners.

Few LGFVs are profitable. Instead of analyzing cash flow, investors look for traces of government support to justify buying these securities. Over time, though, more and more LGFVs that aren’t funding infrastructure or social welfare projects will be called out. Amid China’s deleveraging drive, some LGFVs have reneged on obligations on trust loans. Investors need to weigh whether this debt could be a bomb that will eventually blow up on them.

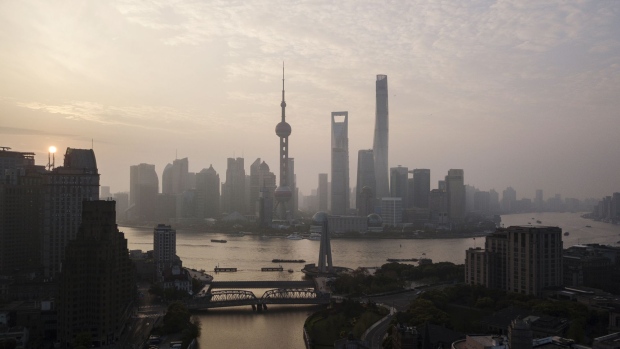

To contact Bloomberg News staff for this story: Tongjian Dong in Shanghai at tdong28@bloomberg.netShuli Ren in Hong Kong at sren38@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jon Asmundsson at jasmundsson@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.