Jan 31, 2023

This Five-Mile-Long Cloud of Methane Was Spotted Over Wyoming

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- It all started with an apparent mistake. Alarms at Tallgrass Energy’s Douglas Gas Plant in Wyoming were triggered by high oxygen levels after a maintenance project didn’t go as planned. The operator told regulators it vented a total of about 2.1 metric tons of methane in five separate safety releases.

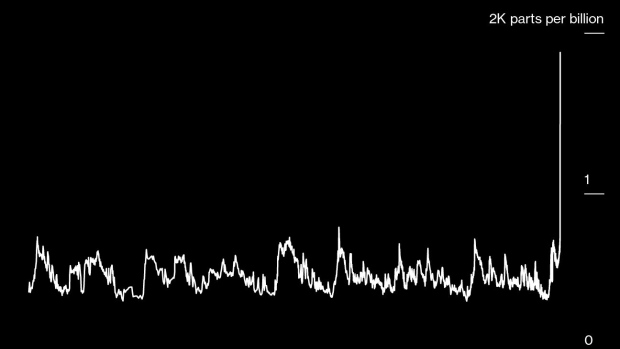

A satellite passing over the US state, however, observed a methane cloud 4.6 miles (7.4 km) long emanating from the location, which scientists estimated was spewing the planet-warming gas at a rate of 76 to 184 metric tons an hour. Because NASA’s Landsat 9 satellite orbits the Earth, the researchers who studied the data couldn’t verify how long the release lasted or calculate the total amount of methane spewed, but said it was likely to be far higher than reported.

“It’s highly unlikely the volume reported by the operator could account for the emissions rate observed by the satellite coming from the facility,” said Manfredi Caltagirone, head of the International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO), an initiative of the United Nations Environment Programme, summarizing the findings of its geospatial scientists.

Methane is the primary component of natural gas and has more than 80 times the warming power of carbon dioxide in its first two decades in the atmosphere. Scientists say cutting methane emissions could do more to slow climate change than almost any other single measure.

Fossil fuels are the second biggest source of methane generated from human activity after agriculture. But leaks and releases from oil and gas operations are among the cheapest to fix and operators have an incentive to minimize emissions because they can recoup the cost of repairs and upgrades by selling the extra gas they capture.

A new generation of high-resolution satellites is revealing that methane emissions from oil and gas facilities around the world routinely go unreported or under reported, with operators sometimes unaware of how much gas is escaping. Kuwait's state oil producer said its monitoring systems never registered a three-week methane leak spotted by satellite last year, while New Mexico authorities said earlier this month they were investigating an undisclosed release near APA Corp facilities.

Companies that can’t control their emissions risk playing a diminished role in the energy transition as buyers increasingly seek producers with cleaner records. A growing focus on ESG credentials also raises pressure on investors to shun companies that aren’t doing more to minimize their impact on the climate.

The issue is beginning to draw regulatory scrutiny as governments look for rapid ways to meet their climate goals. One-hundred and fifty countries have pledged to cut methane emissions at least 30% by the end of the decade from 2020 levels. The IMEO is the most high-profile public effort to date that attempts to identify and attribute the world’s methane emissions through satellite observations. Through its Methane Alert and Response System that was launched at COP27, the group aims to engage with governments and operators to curb methane emissions.

IMEO estimates of the Wyoming emissions were based off an observation made at 10:43 a.m. on Dec. 7 by NASA’s Landsat 9 satellite. The location and timing of the observation match a release Tallgrass reported to regulators in an email sent Dec. 8, which was obtained by Bloomberg through a public information request.

In that email, Tallgrass reported five emergency releases it made on Dec. 6 and 7. One of those releases started at 8:50 a.m. and ended at 10:50 a.m. on Dec. 7 spewing, according to the company, 0.64 tons of methane. It overlapped with an observation from NASA’s Landsat 9 satellite.

Geospatial scientists with the IMEO, which is supported by the European Commission, said the same release was also detected by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-3 SLSTR satellite at 9:48 a.m. and again at 10:27 a.m. and the agency’s Sentinel-5P satellite.

Tallgrass said in its Dec. 8 email to regulators that it hadn’t yet conclusively determined the source of the high oxygen levels but believed they were caused after a pipeline project “inadvertently” wasn’t completely purged of residual oxygen.

“We provided a report to the state, and should we find that our reporting needs to be amended, we will take the appropriate action,” it said in response to questions from Bloomberg. “We are committed to operating in full accordance with regulatory requirements. A paramount focus for Tallgrass is the safe and reliable operations of our facilities.”

Although in some rare cases deliberate releases from energy operations may be necessary to avoid a potential explosion, many intentional emissions can be avoided through more rigorous maintenance, said Steven Hamburg, chair of the scientific oversight committee at the IMEO, who is also chief scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund, a non-profit expected to launch its own methane-detecting satellite later this year. Hamburg’s comments were about the oil and gas industry at large and not specifically Tallgrass.

The pipeline company, which has oil and gas conduits across the US, was bought in 2020 by a consortium including Blackstone Inc and GIC Pte., Singapore’s sovereign wealth fund. Blackstone referred questions to the operator. GIC declined to comment.

An official with the US Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration said pipeline operators are required to disclose natural gas releases that meet certain criteria but that the agency didn’t find any National Response Center notifications during December for the area in question. The agency is “working on a rulemaking to establish additional protocols, aimed at reducing all leaks from regulated pipelines.”

©2023 Bloomberg L.P.