Jan 9, 2020

This Is the Scariest Gauge for the Bond Market

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- At this point, few superlatives are left to describe how historically expensive the bond market looks. The 30-year Treasury yield is just a few months removed from an all-time low of 1.9%. U.S. investment-grade corporate debt just posted its best year since 2009, returning 14.5%. Junk bond yields hit a five-and-a-half-year low of 5.08% and could keep going.

Jeffrey Gundlach, DoubleLine Capital’s chief investment officer, sounded off on some of this during his annual “Just Markets” webcast earlier this week. He said long-dated Treasury yields are bound to rise and that double-B rated junk debt is one of the worst fixed-income investments available. But it’s his deputy CIO at DoubleLine, Jeffrey Sherman, who has a measure of the unprecedented market that might just be the scariest gauge of all for bond traders.

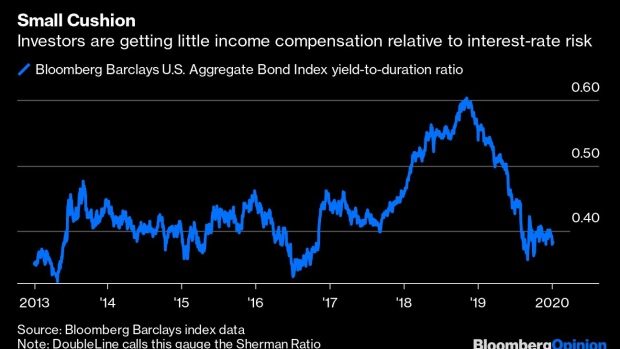

The “Sherman Ratio” measures the yield on a bond, mutual fund or index relative to its duration. Consider the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index (frequently called “the Agg”). This ratio, which effectively shows the amount of yield investors receive for each unit of duration, is close to the lowest level ever, meaning it would take a smaller move higher in interest rates to wipe out the income return on a fund tracking the index:

A drop of this magnitude in any ratio usually requires the numerator (in this case, yield) to fall while the denominator (duration) increases or at least holds steady. That’s exactly what happened in 2019. The yield on the Agg dropped 97 basis points, to 2.31% from 3.28%, while duration was unchanged at 5.87 years.

At first glance, that move doesn’t seem so out of the ordinary. After all, the benchmark 10-year Treasury yield fell 77 basis points during 2019, so it follows that the broader bond market, which includes a large chunk of U.S. sovereign debt and agency securities, would do something similar.

Digging a little deeper, it’s the corporate-bond market where the trend looks truly frightening.

The Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate Bond Index posted a record-low yield-to-duration ratio just last week after a relentless decline in 2019. The reason is simple: Like the rest of the debt markets, the index yield tumbled last year, by 136 basis points. But unlike the Agg, which had no change in its duration, the duration of the corporate-bond index surged to 7.89 years from 7.1 years, the biggest yearly increase in three decades.

Before shrugging off the record low as not far off from previous troughs in mid-2016 and mid-2013, it’s worth noting that the share of the corporate-bond index rated in the triple-B tier has surged in recent years. Triple-Bs are now slightly more than 50% of the index, up from 42% in 2013. So even though the investment-grade index has become riskier on the whole, the yield pickup hasn’t reflected it.

This has significant implications for anyone invested in a passive mutual fund or exchange-traded fund that tracks the Agg or the broad corporate-bond market. DoubleLine explained it well in a 2015 report:

“Particularly helpful when comparing funds, the Sherman Ratio, the result of yield divided by duration, allows one to easily calculate what percentage increase in rates will offset a bond fund’s yield. For example, it would take a 100 basis point rise in interest rates over twelve months to offset the yield of a fund whose Sherman Ratio equals 1.0. The lower the Sherman Ratio, the less rates need to rise to offset one’s yield.”

This also shines some light on a phenomenon I wrote about last month: The collapsing yield spread between triple-B and double-B rated bonds. The difference reached just 33 basis points on Dec. 18, the smallest in at least 25 years.

Part of that story is that investors are clamoring for companies with double-B credit ratings because they’re speculative grade and offer extra yield while still having relatively little default risk. But the other reason for the tightening spread comes back to duration. While the modified adjusted duration on the triple-B index rose in 2019 to 7.86 years from 7.1 years, the duration on the double-B index plummeted by the most on record, to 3.51 years from 4.35 years. When adjusting the indexes for their changes in duration, the yield-spread compression looks far less dramatic.

Of course, these stealth changes to duration are only alarming if interest rates move higher. For now, the Federal Reserve has signaled it will take a material change in the economic outlook for officials to consider lowering interest rates again, and the bar for raising rates is so high that many see it as practically nonexistent. The one wild card is a bigger-than-expected increase in inflation, which investors like BlackRock Inc. say is a real risk in 2020.

Gundlach, for his part, also sees a good chance that inflation will pick up. He said in his webcast that the the 10-year Treasury yield should be around 2.1% or 2.2%, which implies a roughly 40-basis-point increase from current levels. As the Sherman Ratio on the Agg makes clear, a move of that magnitude would be enough to about wipe out its yield.

“One thing that seems clear as the decades have rolled on with this debt scheme, it takes less and less of a rate rise to break the economy,” Gundlach said. “We keep getting lower and lower interest rates that precede recessions, and that seems likely to be the case this time.”

The same holds true for bond investors. The income cushion they once enjoyed just isn’t there anymore. Since 1974, U.S. Treasuries have posted negative annual total returns only four times. Two of those were in the last decade. Similarly, since 1981, corporate debt has lost money just six times, but that includes three of the past seven years.

The bond market feels as if it’s at a crossroads. Perhaps that’s why so many forecasts for 2020 are for benchmark yields to trade in a range and for credit markets to produce a return that equals their interest payments. There’s not much room for interest rates to fall, but there’s little reason to expect they’ll move higher in a hurry, either.

Thus the importance of the yield-to-duration ratio. It’s a simple reminder that lower-for-longer interest rates come with their own set of risks. In a market full of superlatives, it takes less and less to shake up the status quo.

To contact the author of this story: Brian Chappatta at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.