Dec 9, 2022

Top Rankings for UK Universities Disguise Risk to Business Model

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Three UK universities are in the top 10 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2023, with Oxford again retaining the global crown. But in an industry that’s such a cornerstone of British soft power, the prestige of the few masks the struggles of the many.

Institutions across the country are fighting to maintain financial stability as staff strike and more international students go elsewhere. In November, 70,000 people at 150 universities protested against falling pay, pension cuts and poor working conditions. More disruption is planned. Meanwhile, the government mooted capping the number of foreign students, a vital source of income.

Politicians and executives have championed higher education as part of the UK’s global brand, pointing to everything from ground-breaking medical research to the alumni of world leaders. But a combination of Brexit and the pandemic have exacerbated the frailties of the rank-and-file places that make up the backbone of the system and even strained the finances of more highly ranked universities.

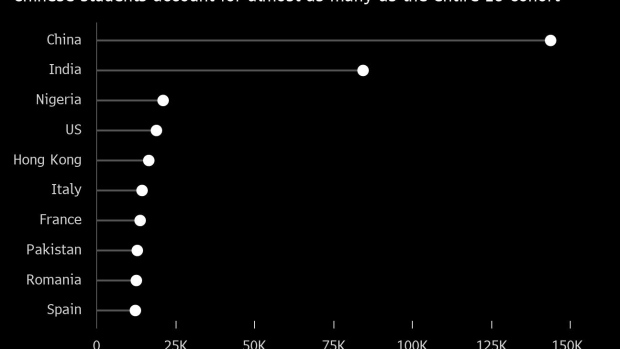

At the heart of the issue, academics on the front line say, is that many are effectively running as unviable companies: they are over-reliant on students from China and India paying higher fees while research grants have been tougher to access since the UK left the European Union.

Almost 30% of 274 universities and colleges were already in deficit at end of the 2021 academic year, according to data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency. That was before energy costs soared and the economy slumped. Even the Russell Group, 24 top institutions including Oxford and Cambridge, told a parliamentary committee earlier this year that the government needed to step in to shore up funding.

Moody’s downgraded Oxford — whose global standing was enhanced further with its work on a Covid-19 vaccine — Cambridge, University College London and others on Oct. 25. A reliance on the UK government’s policy decisions for tuition fees, teaching and research funding caused the ratings agency to change their outlooks to negative.

“You’ve got an extremely constrained business model,” said Karin Lesnik-Oberstein, a professor of critical theory at the University of Reading, ranked 198th in the Times global survey. She called the funding system “hopelessly compromised,” dependent “largely on the money of overseas students, largely Chinese students.”

Figures published by the Office for National Statistics last month showed that students made up the largest proportion of foreign arrivals in the year to June 2022, contributing to a record net jump in immigration. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s administration said it would seek to redress that by reviewing what it called “low-quality degrees.”

Yet numbers suggest lower-ranking British universities are falling out of international favor anyway. Brexit has caused them to lose European applicants while higher performing international students are less willing to pay top dollar for a product that may be losing its allure.

The most recent Universities UK data show that new enrolments from China fell for the first time last year, dropping 4.9% to 99,160 students. While Indian enrolments climbed almost 27%, the rate of growth is slowing.

That could be the tip of the iceberg, according to Julian Fisher, vice-chair of the British Chamber of Commerce in China and co-founder of market research firm Venture Education. He predicted a major drop-off of Chinese applicants to British universities within the decade as government policy in Beijing and a cooling of relations with the UK deter students.

A government report published in June on the financial sustainability of the English higher education sector expressed concern about a “heavy dependence on their ability to continue growing overseas student numbers.” Past predictions were “over-optimistic,” it said.

In addition, those returning with UK business degrees — the most popular study area across the British university system — are struggling to find jobs, said Fisher. There’s also a perception in China that UK degrees are weaker now than their counterparts in, say, the US.

“Increasingly, UK universities have just looked at Chinese students as an entire block from which they can generate revenue and I think it’s quite insulting,” said Fisher, whose firm works with the UK’s admissions office UCAS. “They’re going to get their comeuppance.”

That said, the UK still punches above its weight in higher education, especially compared with the rest of Europe, and has been cementing ties with Commonwealth countries since leaving the EU. Figures show that more Indian, Pakistani and Nigerian students are applying than ever before.

The UK and India signed an agreement in July aimed at boosting applicants further. “UK universities are rightly the envy of the world and international education is one of our finest exports,” said James Cleverly, secretary of state for education at the time.

Many universities and their staff are getting more desperate, though. The University and College Union has reported that more than half of employees showed signs of depression, with 21% of academics working an extra 16 hours per week on top of contracted hours.

Post-Brexit funding chaos has complicated access to research money. In November, the EU’s refusal to grant the UK access to international science programs forced the government to plug a £484 million ($591 million) gap in resources.

Universities UK, which represents 140 institutions, is calling for talks nationwide about the financial viability of the industry. The organization says that funding is forecast to drop to the lowest when adjusted for inflation since the 1900s.

“The one thing that many viewpoints can agree on is that changes are needed to the current system,” said Jenny Higham, a University of London professor who leads funding policy at Universities UK. “It is time to have bold and serious discussions about a solution to this.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.