Oct 22, 2018

Toronto's arc toward playground for rich drives mayoral showdown

Toronto votes for a mayor on Monday to take command of a city in danger of becoming a victim of its own success.

Incumbent John Tory, a quick-talking former telecom executive, has about a 30-point lead in the polls over nearest rival Jennifer Keesmaat, the city’s former chief planner. Whoever wins faces a booming metropolis at a critical juncture: Housing is becoming so unaffordable and transit so gridlocked it’s at risk of turning into just another global playground for the rich.

The candidates may come from opposite ends of the political spectrum -- wealth, says Tory, is created by the private sector and consumed by government; the private sector, argues Keesmaat, has had its way for far too long. But in recent interviews with Bloomberg News, they both pitched platforms that has the city playing a far bigger role in the development of affordable housing.

“We cannot let the city turn into a city that is home only to people who are comfortable and people who are really struggling,” Tory, 64, said at Bloomberg’s Toronto offices.

Keesmaat, 48, agrees: “If we don’t fix that missing piece, it presents an incredible risk to our city.”

Tech Booms

Some mayors might kill for Toronto’s growth. Gross domestic product in the city of 2.8 million people has been running at about 3.4 per cent for the past three years, above its not inconsiderable population growth of 1.6 per cent, according to a city report. Already boasting the largest financial sector on the continent after New York, it’s now in a frenzy of high-tech hiring, adding about 87,800 jobs from 2013 to 2017, the largest five-year gain in at least three decades. The unemployment rate is riding an 18-year low of 6.3 per cent.

While Alphabet Inc.’s Sidewalk Labs plans a futuristic digital city on the waterfront, Amazon.com Inc. is considering Toronto for its second headquarters -- the only city outside the U.S. to make its short list.

The city’s swagger can be seen in its vibrant restaurant sector, Drake-fueled music scene, boisterous, multi-ethnic suburbs and the forest of cranes on its skyline. The city currently has 196 high-rise buildings under construction, the most in North America, according to Skyscraperpage.com.

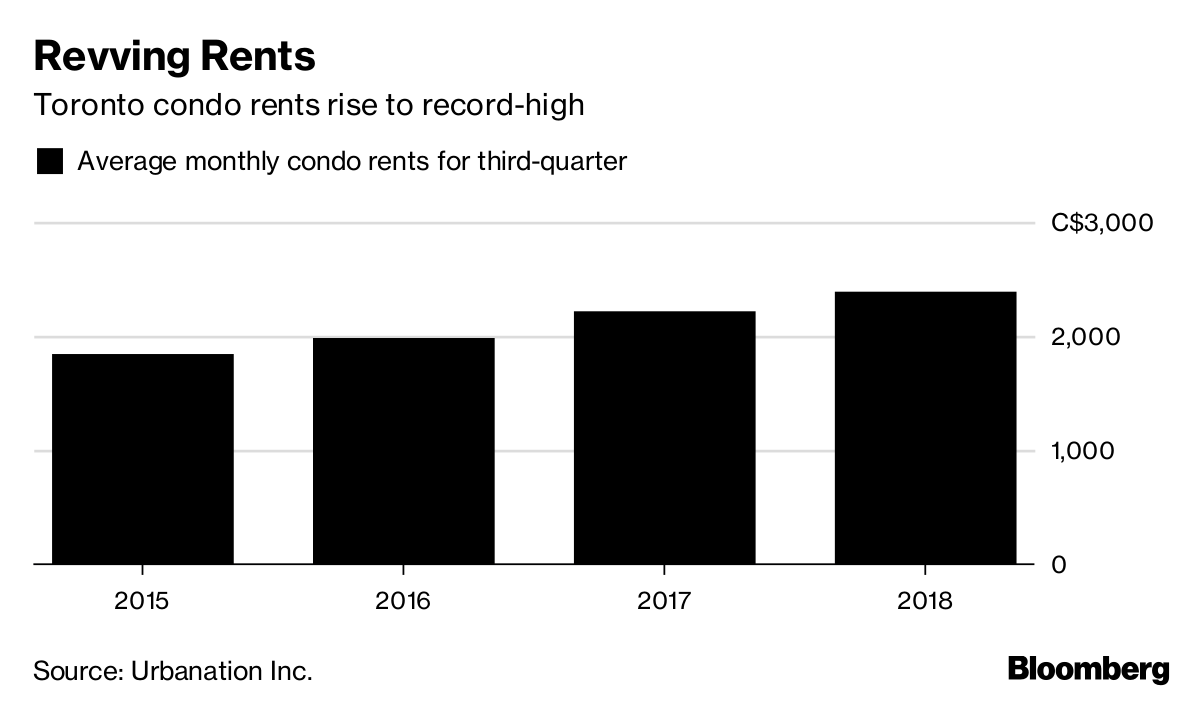

But with big-city growth has come big-city problems, the most crucial of which is housing. Up until the last few years, there’d been little purpose-built rental constructed in the city, leaving renters at the mercy of a condo market that saw average rents soar 7.6 per cent to a record $2,385 a month in the third quarter from a year ago.

The cost of carrying a house -- which averaged $864,275 in September -- gobbles up a record 76 per cent of a typical pre-tax household income when including mortgage payments and various running costs, according to September report from Royal Bank of Canada.

Vancouver Election

To be sure, cities around the world are grappling with similar housing woes. On Saturday, Vancouver elected Kennedy Stewart, a former New Democratic Party member of parliament who has also pledged to increase the supply of affordable housing. The acceleration of growth in Toronto, where a decade ago a family could still afford a house within walking distance of the financial core, has been headspinning.

While both Tory and Keesmaat said the need for affordable housing is acute, they differ in their plans for scale and execution.

He plans to entice developers to build 40,000 affordable housing units over 12 years by canceling or deferring development charges, taxes, and offering cash incentives that could amount to at least $30,000 per unit, or about $120 million a year. He’ll offer up city land for the purpose and expects money from the federal government’s National Housing Strategy to start flowing in 2019.

Transit Gridlock

She says nothing short of 100,000 affordable housing units will do. Her plans is for the city to offer more than 8,000 parcels of city-owned land over 10 years to developers that will agree to construct purpose-built rental at 80 per cent of average market rents. She’ll also require 20 per cent of private-sector developments be affordable. Like Tory, she’ll seek funding from the federal government and will also put a .001 per cent tax on houses worth more than $4 million. That will help generate $80 million a year for a rent-to-own program.

As for transit, the U.K.-based Expert Market ranked Toronto sixth-worst out of 74 cities around the world for commuting, including on buses and trains, and the worst in North America. There has been a few new expansions over the years, including a $5.3 billion light rail line currently chewing its way across the city but investment has failed to keep up with demand as politicians push their pet projects amid never-ending debate over which direction the city should go. The last truly visionary piece of transit in the city may well have been the Bloor Viaduct. When finished in 1918, it had the bold idea to include train tracks under its bridge.

Tory’s answer to the transit woes is a SmartTrack plan that includes a downtown relief line, a waterfront line, and subway extensions, for which he says he’s secured $9 billion in funding from other levels of government. Keesmaat favors the “Paris model” of continuous transit building, putting forward a $50 billion 30-year plan that knits together subways, light rail, streetcars, and buses.

There’s certainly no love lost between the two. Tory called her housing plan pie-in-the-sky and blamed her for many of the development delays in the city when she was planner. She said his model of subsidizing developers was the city’s “dirty little secret,” and described his transit efforts “an incredible underachievement.”

There’s no doubt Tory, who’s been in office since 2014, has returned a measure of sanity to Toronto after the three-ring circus that was municipal government under crack-smoking Mayor Rob Ford. Whoever wins on Monday will have to take city-making to a higher plane if Toronto is to retain the energy that’s taken it to where it is -- without squeezing a large chunk of the population out.