Nov 4, 2022

Trader Arrested in Ibiza Awaits FX Case That’s Dividing Wall Street

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) -- Over almost three decades in the City of London, the aggressive trading strategies of Glen Point Capital co-founder Neil Phillips made him few friends even as they burnished his reputation as a hard-charging trader.

Those sharp elbows have now drawn the attention of the US Department of Justice, which charged Phillips with market manipulation in September. The move sent shockwaves from the Spanish island of Ibiza -- where he was arrested on vacation and is now awaiting an extradition hearing -- all the way back to Wall Street.

Prosecutors claim that Phillips traded heavily in the South African rand in order to force the success of a separate all-or-nothing $20 million bet that the currency would hit a specific level, a once-widespread strategy that’s known in the industry as ‘barrier chasing.’

The US says this is fraud. For many on Wall Street, it’s just combat.

The case could become something of a referendum on what’s considered fair in the market for foreign exchange, a $7.5-trillion-a-day market that is generating immense profits for traders amid rising interest rates and wild swings in the values of currencies.

“It’s fair game if there’s risk behind it,” said Joseph Pach, a former head of currency trading at a Bank of New York Mellon Corp. subsidiary who now runs San Francisco-based trading firm Corcovado Investment Advisors. “If a trader wished to influence the market, they do so by taking on risk that could backfire, with potentially dire consequences,” he said, while noting he’s never engaged in barrier chasing and declining to comment on the specifics of Phillips’ case.

Free Speech

Pach’s view is echoed by multiple traders across Wall Street, including those who have overseen currency businesses at banks and hedge funds. They draw a line between barrier chasing and other controversies that have battered the FX industry such as collusion, insider trading and front-running clients. One compared it to defending free speech: I don’t like what you’re doing but I’ll back your right to do it.

Not everyone is so sanguine. The UK’s Financial Conduct Authority has warned in the past that the practice raises questions around conflicts of interest, conduct and client confidentiality. And the Commodity Futures Trading Commission takes a similarly dim view.

“If the motive is just to move the market to profit on some other position, then that would be manipulation,” said Richard Shilts, an adviser at law firm Steptoe & Johnson who previously worked at the CFTC for about four decades and served as director of the agency’s division of market oversight. “And the CFTC would view it as such.”

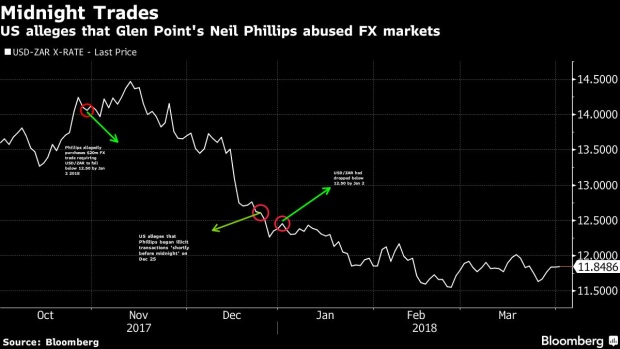

Christmas Trades

The US accuses Phillips of buying $725 million of rand in the early hours of Dec. 26, 2017 in order to push the exchange rate with the US dollar below a barrier of 12.50. This triggered a $20 million payout from another bet he had made through derivatives known as FX options, prosecutors say.

Read More: Soros-Backed Fund’s Christmas Night Trading Frenzy Led to Arrest

Spanish authorities arrested Phillips about two months ago as he prepared to board a flight back to London, where he’s looking to sell a mansion near Hampstead Heath. A court ordered his release in late September but directed him to hand in his passport and remain on Ibiza, the Balearic island best known for its hedonistic nightclubs, Bloomberg has reported. He is currently renting an Airbnb property there.

Phillips, who has yet to file a response to the charges, declined to comment.

Barrier chasing revolves around FX options, financial products arranged by Wall Street banks and popular among hedge funds that use them for high-risk geopolitical wagers. The exotic version that Phillips allegedly bought -- known as a “one-touch digital barrier option” -- is an all-or-nothing bet on a currency rising or falling past an agreed price, or ‘barrier.’

The chase then takes place in the far larger spot FX market, where trillions of dollars are traded every day and help set benchmark foreign-exchange rates. If an FX option investor can find a time of day when there is little trading activity, or has chosen a lesser-traded currency to bet on, the people said, he or she can go into the spot market and nudge the rate toward or away from the barrier and pick up a handsome payout -- or avoid handing one over.

Barrier chasing used to be a regular occurrence and veteran players say they have witnessed it multiple times. They talk of watching exchange rates make sudden moves, not because of a shift in a country’s politics or economic prospects, but as banks and hedge funds battled to attain or avoid payouts. A former head of FX options at a large European bank said the practice dwindled during years of rock-bottom interest rates but could make a comeback now that currency markets are more volatile again.

One trader, who worked across the industry in the 1990s, described buying billions of yen in an unsuccessful bid to push the rate past a barrier. Another described an uncomfortable moment at Bank of America Corp. in 2012 when a senior FX options trader emailed multiple colleagues on the spot-trading desk asking them to keep his team’s positions in mind that day. The trader left the firm shortly after.

William Halldin, a spokesman for Bank of America, declined to comment on the incident beyond noting the Charlotte, North Carolina-based lender has “policies and monitoring specifically to avoid barrier chasing.”

Barrier chasing is still “rumored to occur quite often,” said Francis Breedon, former head of FX research at Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. and now an economics and finance professor at Queen Mary University of London. It distorts the market but is hard to prove as it can be made to look like “legitimate trading,” he said.

To be sure, there will often be a flurry of trading activity linked to FX options that has nothing to do with barrier chasing. The risk of losses can grow as barriers get closer, causing investors to buy or sell the underlying currencies in the spot market to protect themselves.

“The boundary between managing risks around key levels and market manipulation needs to be understood and respected,” said Kit Juckes, chief FX strategist at Societe Generale SA. “If a trading strategy swims, quacks and flies like a manipulative duck, it’s going to attract a regulator’s interest.”

In Phillips’s case, prosecutors cite chats where he allegedly insisted the level hit a certain rate, telling a trader “My aim is to trade thru 50.” That’s a reference -- the US claims -- to pushing the exchange rate between the US dollar and the South African rand below 12.50.

Market Splatting

Phillips, who worked at Lehman Brothers, Morgan Stanley and BlueBay Asset Management over a career dating back to the 1990s, was familiar with the bruising side of trading. He was known in the City for selling large volumes of bonds and currencies to multiple banks at once while leaving them unaware of the other transactions, people who’ve worked with him said. Known as “splatting the market,” this often resulted in the securities losing value immediately after the sale, they said.

The practice made Phillips unpopular with traders at some banks, who came to view him with caution.

This didn’t stop Phillips from attracting some of the world’s biggest investors when he co-founded Glen Point in 2016. Alongside George Soros, other backers included Future Fund, Australia’s A$194 billion ($123 billion) sovereign wealth fund, and the $183 billion Teacher Retirement System of Texas, filings show.

Glen Point closed earlier this year after an aborted merger with rival hedge fund Eisler Capital. Spokespeople for Soros and the Teacher Retirement System of Texas declined to comment. A spokesperson for the Future Fund said it placed the investment under review in 2021 and terminated the investment in Glen Point at the start of 2022.

Regulatory Gap

With no formal clearinghouse like the New York Stock Exchange, the vast majority of currency trades take place between banks and investors, in what’s known as “over the counter” trading. Such transactions are difficult for authorities to track.

“FX is opaque in certain important ways,” said Carol Osler, a professor of financial markets who specializes in foreign exchange dynamics at Brandeis University’s International Business School. “There are no global regulators for foreign exchange. There are very few reporting requirements.”

Given that regulatory gap, market players and central banks decided to draw up their own rules. In 2017, the Global Foreign Exchange Committee established a code of conduct that financial institutions can sign onto. Although the most recent version doesn’t mention barrier chasing by name, it does include an illustrative example that’s strikingly similar. Even still, codes only go so far in their ability to change behavior, according to Osler.

“That’s why the DOJ right now is making a big splash with this,” Osler said. “They’ve made it very clear in their statements: they’re intentionally trying to send a message.”

Real Risks

Defenders of barrier chasing point to the lack of collusion and the daunting task of venturing into the sprawling spot FX market and taking real risks that could blow up.

But taking risk is not a catch-all defense, according to Rosa Abrantes-Metz, an economist who co-heads Brattle Group’s antitrust practice. Any manipulator of markets is likely to take risk and incur some costs, she said.

“We have seen this before in FX,” said Breedon, the professor at Queen Mary university. “Traders think some type of behavior is normal and allowable simply because no one has yet been caught by the regulators.”

--With assistance from Macarena Muñoz and Rodrigo Orihuela.

(Adds details of arrest to eleventh paragraph.)

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.