Mar 7, 2022

Traders surrender to recession paranoia in U.S. market rout

, Bloomberg News

Selling equities on any bounce here is appropriate: Blue Line Futures' Phillip Streible

When it’s just the yield curve narrowing, or oil jumping, or stocks falling into a correction, maybe you can hold off on panicking over a recession.

When all three happen at once, the argument gets stronger that it’s time to take the threat seriously.

That’s the case now, when a concerted move in the direction of nervousness on the part of stocks, bonds and commodities is forcing traders into a real-time reassessment of their expectations for growth.

Such concern may seem misplaced when the U.S. economy just generated 678,000 jobs in a single month, and few observers see a downturn in the immediate future. At the same time, markets are relentlessly forward-looking, and their common message is getting harder to overlook. The S&P 500 sank almost 3 per cent Monday and oil approached the highest price in a decade, while nickel and wheat were the latest materials to surge. Taken together, the message now suggests the threat of an economic retrenchment has increased amid war in Europe and a staunchly hawkish Federal Reserve.

“Prospects for growth have to be marked down and that risk of recession has to be marked up,” David Donabedian, chief investment officer of CIBC Private Wealth Management, said by phone. “If oil goes to US$125 or higher and stays there for six months, you’re going to have a recession in Europe just because of their ultra-high sensitivity to Russian imports.”

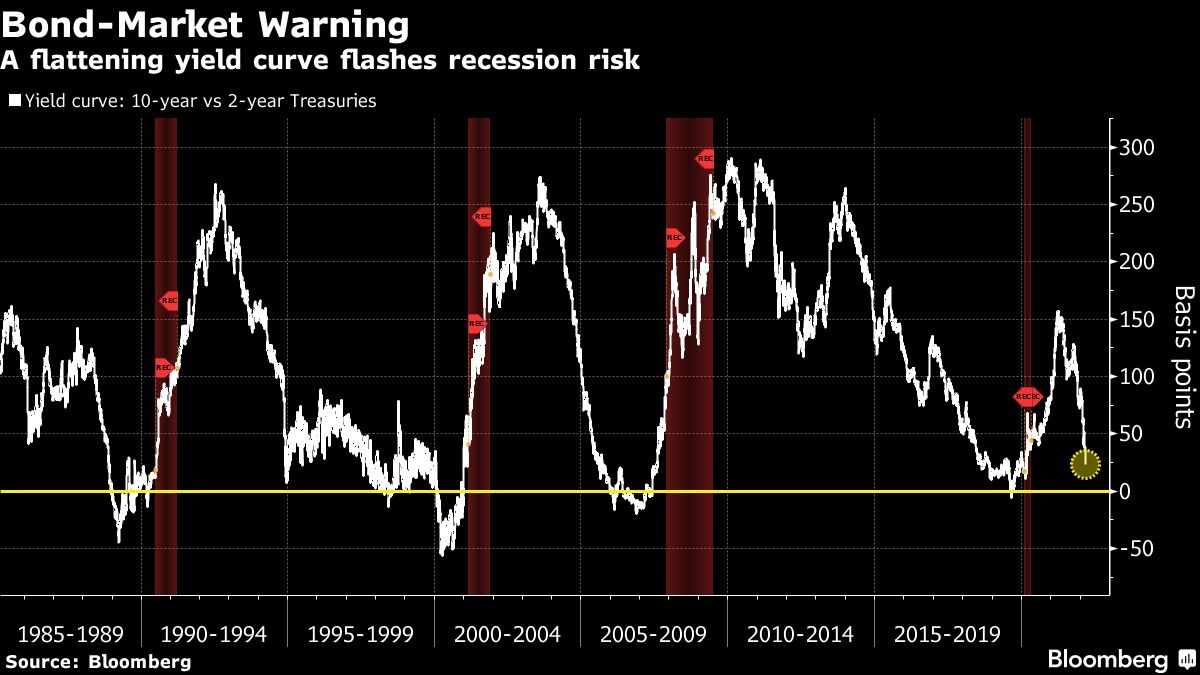

The specter of stagflation, a rare combination of surging prices in a constricting economy, is showing in the bond market. Ten-year inflation breakevens just increased to the highest level since 2005, while the yield curve -- the spread of 10- over two-year Treasury yields -- narrowed to levels not seen since the pandemic recession. History shows an outright inversion, as happened in 2019, would signal an imminent contraction.

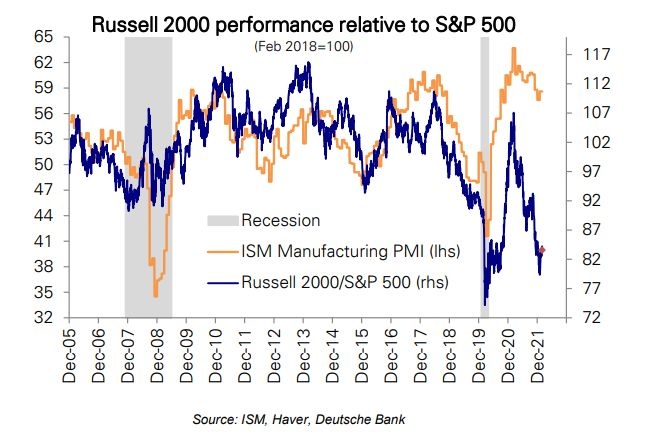

In the equity market, benchmarks from Europe and Asia are heading for bear markets -- declines approaching 20 per cent from their recent peaks. While the S&P 500 fared better thanks to its haven status and distance from Russia, with peak-to-trough losses limited at 12 per cent for now, an analysis by Deutsche Bank AG strategist Binky Chadha suggested American stocks are emitting their own troubling signals.

Plotting the velocity of equity gauges over their trendlines against the ISM manufacturing report, Chadha found that the S&P 500 is pricing in a plunge in the factory gauge to 48 -- below the level consistent with growth. Small-cap stocks reflect deeper troubles. The Russell 2000, which is already in a bear market, appeared to price in a manufacturing reading of 40, a level indicating a “severe recession,” he said.

Over the past week, at least three Wall Street strategists lowered their 2022 year-end targets for the S&P 500, which closed Monday down more than 12 per cent from its all-time high. Market veteran Ed Yardeni, citing rising recession risk, slashed his target for the S&P 500 for a second time in as many months. At 4,000, his new projection implies a 17 per cent drop from the index’s peak in January.

“We can all hope for the best, but preparing for the worst (or worse than we’ve already seen) is the prudent risk strategy right now,” Peter Tchir, head of macro strategy at Academy Securities Inc., wrote in a note.

There’s a point in stock and bond markets when price action stops being a sign of trouble and starts to become a cause: people’s sense of wealth wanes, investment decisions are shelved. That’s the risk in commodities right now, where soaring prices threaten to crimp consumer sentiment.

From wheat and corn, oil to copper, prices are soaring after Russia’s invasion in Ukraine sparked concern over a shortage of supply from two of the world’s largest producers. While the rallies may have begun months ago in the face of booming demand -- the opposite of a recession signal -- many traders see the latest leg as something that could by itself kick the world into a downturn.

The surge in energy prices is particularly ominous. Not only does it strain household consumption, it adds to price pressures, potentially spurring central banks around the world to tighten monetary policy to battle inflation.

“The oil prices, as well as the yield curve and where we are in the cycle, are certainly raising recessionary signals,” Victoria Greene, founding partner and chief investment officer at G Squared Private Wealth, said by phone. “I’m not saying the sky is falling tomorrow. But I do think it’s certainly in the cards over the next 12 months.”

But Neil Dutta, head of economics at Renaissance Macro Research, says concerns over an oil shock are overblown. Not only are Americans today in a better financial position to weather high energy bills, real interest rates remain deeply negative, leaving ample room for the central bank to hike rates without derailing the economy, he argues.

“I have some sympathy for the idea that the Fed’s response to higher energy prices exacerbates the downside shock, but we are far from this point,” Dutta wrote in a note. “Consumers continue to have a high level of excess saving that can act as a shock absorber to oil prices.”

To be sure, markets constantly over-react. Panic takes over investor psychology, and asset prices outrun anything that’s justified by fundamentals. Markets are under multiple threats, and there are arguments against projecting the message of any of them to the global economy. According to one, the pandemic itself is a brake on oil’s impact -- so many people are working at home that the tax imposed by surging fuel prices might be mitigated.

To Zhiwei Ren, portfolio manager at Penn Mutual Asset Management, the current volatility is being driven by geopolitical turmoil that might swiftly reverse should a cease fire take hold in Ukraine.

“How can we be going into a recession if we had such a strong non-farm payroll number?” Ren said by phone. “The current signal is kind of gloomy for the economy down the road, but it’s not driven by economic data. It’s driven by the geopolitical events, so I don’t know if it’s as valuable.”

Indeed, for now, economists expect solid growth in the U.S. economy every quarter during the next year. But forecasts such as those haven’t always been of much use in the past.

A 2014 study by Prakash Loungani of the International Monetary Fund found that not one of 49 recessions suffered around the world in 2009 had been predicted by the consensus of economists a year earlier. Loungani previously reported that only two of the 60 recessions of the 1990s had been anticipated a year in advance.

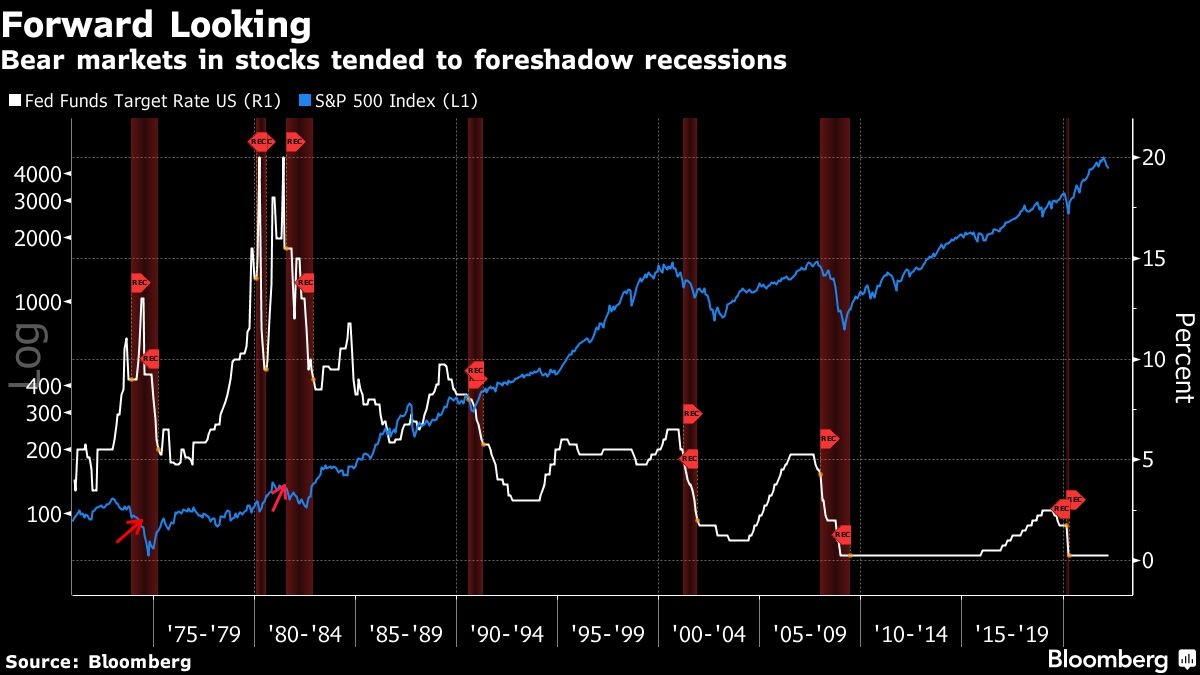

While it’s not saying much, the market has shown a better record in predicting recessions, with signals strengthening as prices snowball. Among all the 20 per cent drops that have hit American stocks since the Great Depression, all but two preceded or coincided with U.S. recessions, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Today’s environment, in some way, reminds Ryan Grabinski, a strategist at Strategas Securities, of what happened in the early 1990s, when Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait fueled a similar spike in oil. Back then, the S&P 500 fell into a bear market and the U.S. entered a recession.

“Perhaps the scary part is that in 1990, the Fed funds rate was 8 per cent and eventually embarked on an easing cycle,” Grabinski wrote in a note. “Today, the Fed is at the beginning of a hiking cycle. It seems more and more likely a recession is unavoidable.”