Oct 20, 2021

Traders Worry Over Ghana Debt Trajectory Ahead of Budget

, Bloomberg News

(Bloomberg) --

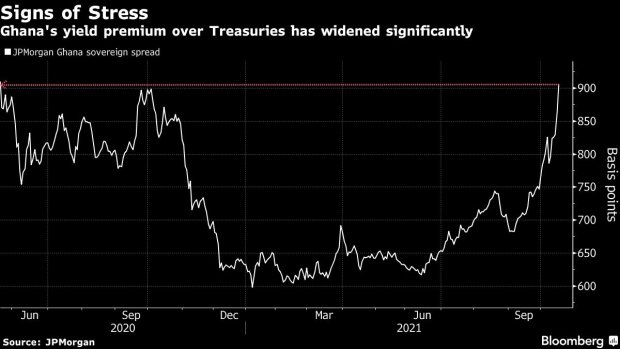

Ghana’s credit-risk premium has soared to the highest since the start of the pandemic ahead of next month’s budget.

It may widen further if Finance Minister Ken Oforri-Atta fails to convince investors that West Africa’s second-biggest economy has a handle on servicing its sky-high debt -- a task made all the more difficult by sluggish economic growth. That raises questions about debt sustainability, according to Ernest Addison, governor of the Bank of Ghana.

The premium investors demand to hold the country’s debt rather than U.S. Treasuries has climbed 139 basis points in October to 905 basis points, the highest since May 2020. The emerging-market average sovereign spread has widened four basis points in the same period to 361.

Ghana’s revenue fell short of target by 12% to 34.3 billion cedis ($5.66 billion) in the first seven months of the year and may continue to do so, pressuring its economic growth outlook. Economists from Redd Intelligence, Renaissance Capital and Capital Economics are already forecasting annual expansion to stay well below the target of 5% in 2021.

Slower-than-anticipated growth will make it harder for Ghana to fund its budget deficit, which is expected to return within the legislated threshold of 5% of GDP by 2024, after breaching it last year. The widening credit spreads also raise questions about the country’s debt trajectory.

“We can grow ourselves out of the debt, but unfortunately if we do not get strong growth then debt sustainability issues will become key,” Addison said in response to questions from Bloomberg. “It’s a serious consideration everybody should be concerned on.”

The yield spread between 2030 notes partially guaranteed by the International Monetary Fund and unguaranteed 2029 securities has also ballooned, suggesting investors are positioning for the possibility of a default. With spreads at current levels, the country will struggle to roll over existing debt.

“Do they still have access to the Eurobond market at these levels? Could they issue one at a reasonable price?,” said Neville Mandimika, an economist and fixed income strategist at FirstRand Bank Ltd. in Johannesburg. “The answer seems to be no.”

Ghana has historically relied on funding from the Eurobond market to fund expenditure. Limited access to international loans could force the government to supply more debt locally, which would be detrimental to cedi yields as banks and institutions already own about 80% of paper.

Ghana’s dollar bonds are the worst performers this month in a Bloomberg index tracking emerging-market hard-currency debt, with a decline of 5.8%. The 2025 yield jumped 153 basis points on Monday, the most in a day on record since the debt began to trade in April this year. It climbed an eighth consecutive day Tuesday by 66 basis points to 11.2%, the highest on record.

“At this point they need to present a credible plan B on how they fund the budget in the abscence of Eurobond issuance,” said Mandimika. “In a worst-case scenario where debt is growing amid a global risk-off mood, Ghana may have to head back to the IMF.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.