Sep 29, 2022

Transcript ‘Zero’ Episode 3: A Big Climate Bill for a New Era of Climate Tech

, Bloomberg News

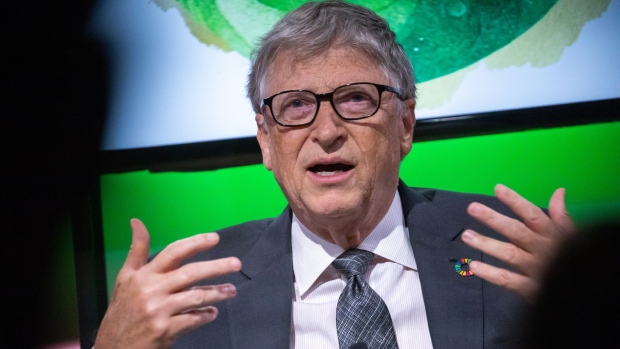

(Bloomberg) -- In Episode 3 of the Zero podcast, Bloomberg Green reporter Akshat Rathi interviews Bill Gates about innovation, degrowth, and the landmark US climate bill. Listen to the full episode below, learn more about the podcast here, and subscribe on Apple, Spotify, Google or Stitcher to stay on top of new episodes.

Our transcripts are generated by a combination of software and human editors, and may contain slight differences between the text and audio. Please check against audio before quoting.

Akshat Rathi 0:00

Welcome to Zero, I am Akshat Rathi. This week: innovation, the US climate bill and the Bill behind the bill.

Akshat Rathi 0:17

My guest today, Bill Gates, hardly needs an introduction. As the co-founder of Microsoft, he has amassed one of the world's largest fortunes, virtually all of which he has promised to give away, mostly through the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. He is also known for his forays into funding new climate technologies. In 2015, he created Breakthrough Energy, an accelerator for green technologies. It has a multibillion-dollar venture capital arm that has invested in nearly 100 companies, and a nonprofit arm that influences policy and conversations around climate solutions. In 2021, he published a book called How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, where he makes an impassioned case for innovation and its essential role in changing our physical economy. But he is also realistic about the timeframe it's going to take.

Bill Gates 1:07

When people say to me, “Hey, we love your climate stuff because we can tell Putin we don't need him.” I say, “Yeah, 10 years from now, call him up and tell him you don't need him.”

Akshat Rathi 1:17

The amount of time needed to bring innovations to scale is one reason why Bill is so keen to make sure governments act on climate. Most recently, he was an influential voice behind the landmark US climate bill called the Inflation Reduction Act. I sat down with Bill in August, before President Joe Biden signed that legislation, to talk about innovation, the role of government, and the biggest challenges in a world facing multiple crises.

*Interview starts*

Akshat Rathi 1:49

Your basic philosophy to tackle climate change has been innovation and you've pledged to give away the majority of your money in your lifetime. But climate change is a time-limited problem: We have to get to zero as soon as possible. And you've also said that we need to do everything we can to accelerate innovation. What's stopping you from giving away all your money to innovation right now?

Bill Gates 2:16

Well, innovation is not just a check-writing process — the cost is way greater than what anyone could fund. Like when I chose to get involved in reinventing nuclear fission. I put about a billion dollars into that. But my key value-add was finding the basic idea for much safer, cheaper, low-waste solutions, and bringing those brilliant people together on the software modeling skills. And, you know, having some realism about how tough it is to create something that not only will pass the regulator's standards, but also be accepted by the broad public. I've been stunned. The leading-edge indicator of seriousness is did the energy R&D budgets go up.

I went to the 2015 climate talks saying, we have not invented an economic way of making aviation fuel, or cement or steel, and we're not even trying. And without those breakthroughs, the brute-force cost, say, of using direct air capture, it just won't ever happen. Without innovation, you will never solve climate change, and the existing tools only apply to areas like electricity generation. They don't apply to most of the emissions. So you know, I'm getting governments involved. Even just this latest bill — where I was personally involved in a lot of what got written into it, and then working with the key senators in the last month to get it to pass — that's far greater than any individual fortune. And I'm orchestrating a lot of people. Breakthrough Energy ventures really entered the climate innovation space at a time when there was almost nothing going on, and by having deep expertise, it's been able to not only do its funding, but also get other funders involved. And the idea of replacing all the physical economy… you're going to have to use markets, you're going to have to use government R&D budgets, and you actually have to find the right people to get behind. It's not just purely a financial thing.

Akshat Rathi 4:39

So you just mentioned your involvement in helping the Inflation Reduction Act. Let's come back to that a little later, but for now, I want to discuss how that bill helps support climate tech innovation. You wrote an op ed in the New York Times where you said this bill can turn American innovations into American industries. How exactly does the bill do it?

Bill Gates 5:03

Well, a lot of the money in there is for things like long-duration storage, green hydrogen, better electricity transmission, direct air capture, [and] manufacturing processes that are zero-carbon emission, including cement and steel. In the very early stages, a new way of making, say, cement will be more expensive. And unless you get it on a volume learning curve, you don't drive that cost down, which means that there's a gigantic green premium, you don't drive it down.

Akshat Rathi 5:39

So to give some context here. Simply put, the green premium is the difference in cost between doing something in a way that produces greenhouse gasses, and doing the same thing without releasing those emissions. Imagine that you're building a home — you're going to need cement. Today, you can buy that cement for about $100 a tonne, but you pay nothing for the carbon dioxide that is released in the making of that cement. If you were to capture the carbon dioxide, it would cost you another $100 per tonne of cement produced. Which means if you were to pay for a zero-carbon cement option, you'd be paying $200 a tonne, twice as much as you would for regular cement. And that difference — the extra $100 — is the green premium. Bill argues that innovation is key to lowering that green premium and making it possible for low-carbon technologies to be adopted all over the world.

Bill Gates 6:31

The magic comes where you have enough time selling at volume — starting with lower volumes and then going up — to where the green premium gets to zero so that you can say to middle-income countries, that are 65% of emissions, this new way of making cement does not have a green premium. Because that's the only way they get to zero. The rich countries aren't going to subsidize trillions of dollars. And the middle-income countries are not going to slow down providing basic shelter to their citizens when they know that the rich countries are responsible for most of the historical emissions. That's what I call the collective action problem, which is only solvable with innovating green premiums to zero. There's no other metric that really counts other than current total emissions and your progress on reducing green premiums. Everything else is kind of a sideshow.

Akshat Rathi 7:34

If we take the stages of innovation, typically it’s scientists funded by governments that invent something in a lab; then comes in risky capital like Breakthrough Energy Ventures, that funds that idea to become pilot scale; then comes less risky capital such as loans from banks, that help create a self-sustaining viable business. The first step, however, is government funding. Now, during the 1960s, the US spent 2% of its GDP on innovation. That's down to 0.5% today. In 2015, during the historic climate talks that led to the Paris Agreement, you tried to make the case for doubling the funding on innovation, but you got nowhere near doubling. You got some increase and now this bill will give you some more increase, but nowhere near double. Why do you think you failed to eke that out, given the case you're making is so strong?

Bill Gates 8:27

Well, we did get very good increases when Obama was in office. We had two good years with significant increases. You're right, even with the Competes bill giving us some additional money, we're nowhere near the doubling. And it's interesting because the NIH, another innovation budget that I have to love related to health … that has grown. So there's a broader political consensus about the medical research budget in the US than there is about energy research. I think it's a mistake, that that didn't happen. And it shifted more of the burden of the invention into the innovative startups. So some of these ideas are not as far along at the basic R&D level as you'd like, which makes these companies even riskier. But hey, if that's the only way to do it, we're gonna fund companies, multiple companies in every area of emission. And I'm surprised how many we found that, at least so far, are making great progress.

Akshat Rathi 9:32

So sticking with the idea of green premiums. There are many ways to bring the green premium down. One way is what you're doing with Breakthrough Energy’s Catalyst Program, where you get companies to voluntarily buy green cement or green steel at a high cost. The more green cement and green steel are made, the cheaper they become. The approach that you're taking relies on the willingness of the companies to do the right thing, but the proven way to drive the green premium has been what governments have done. They put mandates on the deployment of say solar or wind, or they provide a tax credit to pay off that green premium. That leads to way more solar panels being made, and the price falls way faster. So surely then, the solution to reduce the green premium is for governments to step in with policy or subsidy? Or how far do you think the voluntary market you're creating with Catalyst can really go?

Bill Gates 10:28

Well, certainly governments are the big numbers. Take the tax credits for the proven technology — electric cars, solar and wind. About half of the tax credits in the bill are to accelerate the proven technologies, where your subsidy per unit is lower, because it's very high volume. But that’s very helpful. Catalyst will be say $2 billion to $6 billion over time, and it will give us a seat at the table to help direct the government tax credit and project money. But that alone wouldn't do it, you absolutely either need a broad carbon tax or specific tax credits, to meet the deadline we have of getting, in all areas of emissions, extremely low green premiums. None of the inventions will be a zero green premium when they first come out.

Akshat Rathi 11:24

And to be specific: on an economy-wide carbon tax, you have said that it has to be high enough, like $100 or $200 a ton. Because if it's too low, it's not going to overcome the green premium thresholds on the products we need.

Bill Gates 11:39

Yeah, in the long run, what you want is a carbon tax that matches your direct air capture cost. And you actually literally collect that fee, and then you spend it on the direct air capture.

Akshat Rathi 11:51

And just so we’re clear, direct air capture here refers to a technology that can remove carbon dioxide directly from the air.

Bill Gates 11:59

You know, for some product categories, that will be the lowest-avoidance dollar-per-ton strategy. Currently, the retail price for direct air capture is in the order of $500 through Climeworks. There are companies that show us how to get it to $200, $150, $100. And even some that look like it can get us below $100. Setting that upper bound is very, very important for the most difficult areas to redesign.

Akshat Rathi 12:30

A fun question for you, because obviously, you watch this space with a different lens, but I think we watch it obsessively together. If there was a sector of the technology space that I had to pick out and say that I've been flabbergasted, amazed, surprised by the sheer number of ideas coming through it, for me that is carbon removal. Is it a different answer for you?

Bill Gates 12:54

I'd say the various agricultural innovations are kind of stunning to me. The basic idea of how does nature make food. For example, there's funding to improve photosynthesis itself, and engineer it to be twice as effective. The idea that that's available … or plants don't have to leak as much water, and so the amount of water you need for crops can be reduced. Or all the things around approaches of making meat, which would have a lot of benefits, including greenhouse gas reduction. I always thought agriculture would be the toughest. But I see a lot of things there. You know, when we opened up Breakthrough Energy, I didn't know that we'd have worthy companies. We built up a very, very strong technical team. And I have to say, the Breakthrough Energy ventures team has been phenomenal at not only identifying companies, but actually starting companies where there was no one pursuing a particular idea.

Akshat Rathi 13:59

So when we talked 18 months ago, your book had just come out and Breakthrough Energy Ventures had raised a second billion-dollar fund. Back then it was invested in 50 companies. Now it is invested in nearly 100 companies, and that second fund, I understand, is nearly exhausted. Are you raising another billion dollars for BEV’s next fund?

Bill Gates 14:19

Yeah, next year, we'll need a BEV3 for additional companies. And then we may also raise a fund that doesn't come in at the early stages, but does later-stage funding. And so we have some investors who have shown a clear interest in that. Even as the ebullience in investing in tech and climate companies is down a bit, I still think we'll be able to raise the money. It's not quite as easy as it was, say six months ago, but yeah, we're looking at a new round for the startups and a pool under the Breakthrough Energy Management that does later-stage investing.

Akshat Rathi 15:04

Bill Gates is without a doubt, a techno optimist, and it's not hard to see why innovation has been the tool of his success. After the break, I ask Bill whether innovation is enough, and we also talk about the broader revolution needed to help solve the climate crisis.

Akshat Rathi 15:28

You're a techno optimist, but the scale of the climate challenge is so much bigger than anything humans have done. It requires the rebuilding of the physical economy so that it produces no emissions. You once told me, when we spoke last time, that if we manage to do this, it would be a bigger achievement than winning the Second World War. But is technology the only innovation we need? Or do we also need a social and political revolution alongside it?

Bill Gates 15:57

Well, I don't know what those words mean. We need more than technology, because we have to have the political will. We're asking society to stop using stuff that, other than for climate things, would last longer. That coal plant, and those jobs, and that natural gas plant, and that way of making cement. We're asking society to walk away from those. Of course, the more you walk away from, say, natural gas, the cheaper it'll be. It'll just be sitting there just as cheap as can be because you're trying to drive demand to zero. Anyone who says that we will tell people to stop eating meat, or stop wanting to have a nice house, and we'll just basically change human desires, I think that that's too difficult. I mean, you can make a case for it. But I don't think it's realistic for that to play an absolutely central role. I mean, after all, if the rich countries completely disappeared, that's only less than a third of emissions, if we all completely just weren't in the picture at all. And those [remaining] two thirds of emissions are pretty basic in terms of the calories and shelter and transport and goods being used. So the excesses of the rich countries … even curbing those completely out of existence is not a solution to this problem. It may feel Calvinistically appropriate, but I'm looking at what the world has to do to get to zero, not using climate as a moral crusade.

Akshat Rathi 17:38

But there are people who are getting louder about the idea of degrowth. They say it's a moral imperative for developing countries to grow so that they can meet their basic needs. And they argue that the planet is finite, which means developed countries have to rein in their excesses. Does capitalism as it exists today allow for such an outcome?

Bill Gates 18:00

I don't think it's realistic to say that people are utterly going to change their lifestyle because of concerns about climate. You can have a cultural revolution where you're trying to throw everything up, you can create a North Korean-type situation where the state's in control. Other than immense central authority to have people just obey, I think the collective action problem is just completely not solvable. And when people say the earth is finite, I don't actually know what they mean. We can grow enough food, the water is not disappearing, the minerals are not disappearing. It's not a Malthusian situation. In fact, other than the continent of Africa, we're actually in population decline. We reached so-called peak baby in the last decade. The only reason we have population growth is not that we have more babies, it's just that lifespans are longer. So there's not like some equation, like some plan B, it can't possibly work type thing. That's not a problem.

Akshat Rathi 19:09

There are four ways to cut emissions through government policy. One: Your tax emissions — you put a price on carbon or have a cap and trade system to mandate emissions reduction. Two: You write some regulations that will force companies to emit less. Three: Reduce fossil fuel production — where you just shut down oil and gas facilities. Four: Subsidize what you want by throwing money at the problem, like tax credits and other subsidies that make green things cheaper relative to dirty things. If we look at the new US climate bill, it's all carrots, no sticks, right? It seems like in the US it's very hard to implement a stick and get the government to actually regulate reduction in emissions. Do you think that threatens our ability to get to zero by 2050?

Bill Gates 19:56

No, absolutely, asking people in this generation to take their expectation of improving standards of living and actually, because of the transitional costs, reduce their standard of living, there just isn't that broad consensus. For example, when France put on a diesel tax, then you got the yellow vest phenomenon. The diesel tax, which was quite modest in the scheme of things in terms of incentives to change, was absolutely repealed. Hey, we live in a political world and the voters in France reacted to that increase. The US hasn't been able to raise the gas tax even to fund highway construction, not to mention climate-related things. So if you're taking more of the improvement in the economy, and putting that all into climate at a time when there's pandemic needs, and the health system costs are going up as people are aging, and helping poor countries for their non-climate related problems, funding the war in Ukraine, you have to push the limit on getting people to recognize climate is important. And if you have one party who's completely not part of that, then you better be realistic about what you're gonna get. So anybody who's broadly convincing Republican voters this is a high priority, God bless them. People who are in the climate space may not realize how many things are competing for the modest amount of increased resources that society has. And that not that many people are prepared to be worse off because of climate requirements. And therefore, how do you square that? Well thank God that the innovation path makes the cost of doing it better. And remember, brute force … I pay $9 million a year. I brute-force eliminate my climate things. Rich companies can do brute force. Some of what they do now, like tree planting, isn't real but even if you get to the real stuff, they could probably afford it. But just having a few rich countries, a few rich companies and a few rich individuals buy their way out so they can say they're not part of the problem, that has nothing to do with solving the problem. Solving the problem is finding innovators building these innovative companies so that you can call up India and say, “Hey, you need to make steel this new way. Cement this new way. Meat.” Actually, they don't use as much meat. So bad example, but, “Do transport this way.” And so, the rich countries dropping their emissions to zero is a nice thing, but it's only 25%. You have to have something that motivates middle income countries, including India, Brazil, China, to completely change these processes.

Akshat Rathi 23:06

Now, what is happening here in Europe with the Ukraine war, and what's going to happen this winter, is going to be spectacularly bad for people because of high energy prices. How do you think Europe should be dealing with this while also holding on to its climate goals?

Bill Gates 23:23

Yeah, it's a very scary situation where natural gas is an important input for heating houses, making electricity and industrial processes. The German chemical industry, a key input is low-cost natural gas. And so overall, that equation of okay, can you use less electricity or shift back to other ways of getting electricity? Well, sadly, right now, the wind’s not blowing well, the French nuclear reactors are partly shut down. The rainfall in Norway is bad. I mean, you know, there's a lot of things that have gone wrong in terms of what that equation looks like for Europe this summer where of course the Ukraine war is the super tough thing. The difference in the amount of natural gas you need in a very cold winter versus a mild winter will surprise people. It's almost a factor of three difference. So you better be hoping it's a fairly mild winter. If so, the tradeoffs are pretty reasonable, in fact, for this winter. If it's a very harsh winter, the tradeoffs are very, very difficult, including clamping industrial use in large part, which people aren't really ready for. Sadly, most of the climate things, you know, at best are 5- to 10-year solutions. So when people say to me, “Hey, we love your climate stuff, because we can tell Putin we don't need him.” I say, “Yeah, 10 years from now. Call him up and tell him you don't need him.” But in the meantime, jobs in the German chemical industry and people not freezing to death, people are still pretty interested in it, and green technologies or even non-green technologies. Build more LNG ships, more pipes. Should you reopen coal plants? Probably. These pragmatics are pretty important. Should that Netherlands’ gas field be reopened? Maybe so. It's a very tough set of tradeoffs. Very unexpected. I think in the long run, it's good for climate. In the short range, you just have to find any solution, even if that means emissions are going to go up. The sooner that war ends, the better. But there's a lot of considerations that go into how to bring it to an end.

Akshat Rathi 25:46

So let's come back to the Inflation Reduction Act.

President Joe Biden 25:50

I'm about to sign the Inflation Reduction Act into law, one of the most significant laws in our history. Let me say from the start with this law, the American people won and the special interests lost.

Akshat Rathi 26:02

This landmark piece of climate legislation almost did not happen. You were one of the people who was involved in enabling it and helping it come through. You were someone who spoke to the Democratic Senator Joe Manchin, who was a deciding vote. Set the scene for me, tell me the story of the call you made to Joe Manchin.

Bill Gates 26:22

Well, my dialogue with Joe has been going on for quite a while. I had a meeting where almost everyone on the Energy Committee came over and spent a few hours with me over a dinner, discussing the role of innovation in climate and how the US had built this opportunity and was really the only country, given how quickly this needs to get done, that has that innovation power. Our universities, our national labs, our risk-taking, our ability to attract the brightest people from all over the world to come together. We've seen in industry after industry how that matters. And those skills matter a lot for this climate innovation. So the idea that some sort of tax credits and project financing would have to be part of the mix — as well as more R&D — that dialogue had been going on for a long time.

Akshat Rathi 27:14

When Joe Biden came to power, he had an agenda that promised on many things, including climate. The trouble is, the two parties in America are extremely divided and rarely vote for each other's legislation. That meant to fulfill any part of Biden's agenda, every Democratic senator had to be on board. What ended up happening was a lot of horse trading over many months, and ultimately, many of the big promises Biden made were delivered, but in three different bills.

Bill Gates 27:44

The project financing came in the infrastructure bill, and some of the R&D increase we wanted actually came in another bill, the CHIPS or Competes Act. But the tax credits were only going to happen in reconciliation format, because you weren't, unfortunately, going to get Republican votes for $300 billion of tax credits related to climate, about half of which are related to new technologies. And so that meant you needed 50 out of 50 senators.

Akshat Rathi 28:18

And that means Biden needed Manchin. But because of the machinations of the US government, that climate bill wasn't just a climate bill. It also included other types of spending on health care and childcare and other priorities that the Democrats had. That became a sticking point.

Bill Gates 28:34

You started with a construct that had a lot of social programs that weren't funded for the full 10 years, even though the tax offset was going over a 10-year period. So it was almost like money was free which, during the low interest part of the macroeconomic cycle, you can get confused about. So it was a very ambitious thing. You would have had to either cut those programs or run up deficits or raise taxes in a way that neither party has shown an appetite for. Anyway, Joe had concerns and he wasn't the only one. But as the bill got to be more of a climate bill on the spending side, he was overall supportive. But there were a variety of things that he had reasons he was concerned about, both for the nation and in some cases for West Virginia in particular. So in maintaining that dialogue, including the last month where people felt like “Okay, we tried, we're done, it failed,” and because I believed it was a unique opportunity, I tried to bridge the communication gap and encourage people to make one more effort. Because of the relationship we built up over time, we were able to talk even at a time when he felt people weren't listening. I wouldn't have wanted to be in his position. The last six months have been challenging. Even just getting in his car and trying to live a normal life. But anyway, here we are, with a fantastic result. Not just this bill, although this bill is the biggest of the three, but also with what's in the Infrastructure and Competes acts.

Akshat Rathi 30:22

You mentioned he came for dinner with the Energy Committee. Were there any other moments that you remember where maybe what you said really clicked and he got it?

Bill Gates 30:32

No, I've learned a lot from Senator Manchin. As part of the dialogue, I went out and had dinner in DC with him. His wife, who works on the Appalachians Commission, was there. We talked about the challenges there and we talked about West Virginia. And with my work in nuclear fission, could that be a state where some of those reactors go in to create jobs that some of the coal mining and coal plants will be eliminated. So it's a respectful dialogue. He's a centrist. It's not easy to be a centrist right now. But he's not the only senator I was talking to, and I have a team in DC that's there to help with any staff group who's focused on climate. So I think everybody's feeling good about the collective effort, although we came close to not getting this key piece. It makes a huge difference, and I wish we were gonna get a lot of opportunities. But this might have been a unique moment.

Akshat Rathi 31:30

Just in the last month, though, there was a moment where it all fell apart, as you said. And people were like, “Okay, this chance is gone.” What is it that you needed to do to make the politics go in the right direction?

Bill Gates 31:43

Well I don't want to take credit for what went on? I mean, Schumer, he said to me, on one call that he'd shown infinite patience. And I said, “You're right. And all you need to do is show infinite plus one patience.” It's tough getting 50 people lined up who have different views. And this is a complex bill. I happened to be in Sun Valley, when Senator Manchin was there. We had talked about what was missing, what needed to be done. And then after that, it was a lot of phone calls with various people. And I kept trying, because I just didn't see another chance except in this one path.

Akshat Rathi 32:25

Would it be fair to say that given the amount of engagement you've had with Joe Manchin to convince him to sign this bill, that this is the biggest thing you've done on climate so far?

Bill Gates 32:37

Now that would be taking credit for a decision that Joe made. And he's always been supportive of the bill. He wasn't… you know… The reason this has been under discussion is not because, people say Joe likes coal or something like that. That's really not fair. Joe wanted to see a climate bill.

Akshat Rathi 32:54

A quick aside, while Bill says Manchin wanted a climate bill, it is also widely reported that Manchin and his family have a financial interest in coal in his home state.

Bill Gates 33:05

And he, in terms of what it did to inflation, or how you funded it, or was it realistic? You know, we need hydrocarbons in the meantime. And we've seen, particularly with the Ukraine challenge, that the transition spreads out over time. And Joe felt both in the area of inflation and what it's going to take to have a smooth transition where the US has cheap energy and stays energy sufficient, that he wanted to see a mix of things. I will say that it's one of the happier moments of my climate work. I have two things that excite me about my climate work. One is when policy gets done well, and this is by far the biggest moment like that. The other is where I sit and talk to these innovative companies. And I hear about this amazing new way to make steel and cement and chemicals. And it's incredible. The green spending had dropped to near zero in 2016. And now, that's been reinvigorated. And the innovation is going way faster than I expected. That's why I'm optimistic that we will solve this thing.

Akshat Rathi 34:32

That was a fascinating conversation. Thanks for coming on the show, Bill.

Bill Gates 34:36

No, it was great. Good discussion. Thanks so much.

Akshat Rathi 34:48

The US is the second largest emitter in the world, and it has been a laggard on climate action. Now that it has passed its biggest climate bill, it was fascinating to hear the inside story of how it all happened. If you want more on that, you can find a long read on Bloomberg Green that I wrote with my colleague Jen Dlouhy.

Thanks for listening to Zero. If you like the show, please rate review and subscribe. Tell a friend or tell your Senator. If you've got a suggestion for a guest or topic or something you want us to look into, get in touch at zeropod@bloomberg.net.

Zero is produced by Oscar Boyd and Christine Driscoll. Our theme music is composed by Wonderly. Many people help make the show a success. Each week, I'll tell you about one of them. Thanks to Jessica Martin. She's the senior audience development editor for Bloomberg Green, and despite all her TikTok dances, runs the most efficient meetings.

I am Akshat Rathi, back next week.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.